Our world continues to change rapidly. The mission landscape we thought we knew so well has shifted underneath us. Globalization and urbanization, along with other significant factors, are creating a new mission reality we have never experienced before. Some churches are finding themselves disoriented and entrenched in ineffective yet comfortable ways of being on mission. Other churches tend to be reactionary in their mission planning, without a biblical foundation guiding their mission. This article seeks to identify some of the significant trends that are impacting world missions. It also identifies three implications that need to be explored in light of these trends. The article concludes by suggesting a process that can be used by church leaders seeking to engage their changing world as participants in an unchanging mission.

Churches seeking to fulfill their role in the mission of God are facing unique challenges and, in some cases, amazing opportunities in our world today. Many American churches are seeking to re-engage in the mission of God. They are searching for ways to renew their mission vision and empower their members to be actively involved in God’s mission both locally and globally. Younger generations are redefining missions as they become involved in global compassion and justice ministries. This raises questions for church leaders. What is the mission of the church, and where should our church invest our funds designated for missions? Churches are evaluating their global mission efforts and often feel that their current efforts are falling short in bearing fruit, making disciples, and reproducing churches in the region to which they have been called. What are the strategies that can best make disciples who make disciples? How do missionaries form communities of faith where followers of Jesus can be formed spiritually? Churches are recognizing that the center of Christianity no longer resides in the Western world and has shifted to the Global South. This reality challenges them to work collaboratively with national leaders and churches in the region where they are called. How do we partner with national leaders as they take the responsibility to reach their people, country, and region of the world? Major shifts in migration patterns are bringing various people groups to the United States. War, conflict, economic crisis, and the search for a better life are carrying some refugees from traditionally Muslim areas into traditionally Christian areas. How do Western churches engage people fleeing their homelands and livelihoods seeking peace and a new start? How do we show them the love of God and provide them with an opportunity to hear and accept the good news of Jesus Christ? This article does not address and answer all of these mission questions facing churches today. It highlights some significant issues and provides a framework for churches that are facing these issues and seeking to discern what God is doing in our world and join him in his mission.

Understanding Global Trends

We are living in a world that is changing in unprecedented ways and at an unprecedented pace. Certain ways of sharing the good news of Jesus and doing church are not as productive as they were in days past. We are living in a post-Christian and postcolonial age. Churches are questioning what answers they can bring to a world suffering from starvation, major disasters, war, conflict, abuse, and injustice. It is creating major challenges for our missionaries, churches, and leaders as they share the good news of Jesus in a world uninterested or hostile to a Christian message. Churches still believe the prophecy of Isaiah 55:11: “my word . . . will not return to me empty, but will accomplish what I desire and achieve the purpose for which I sent it.”1 Yet, they struggle to understand the times and join God in his work in the world.

So what are the current trends and how might God be working through them for his purposes? Fritz Kling provides helpful insights into some global mission trends in his book, The Meeting of the Waters.2 His research team went on a Global Listening Tour, which carried them around the globe for ten years looking for trends that are reshaping churches everywhere. Kling identified what he refers to as seven global currents that flow “invisibly and powerfully, under and around the global church.”3 These global trends are:

Mercy: Social justice has become a global imperative, especially among younger generations. Mission that submits to a false dichotomy of spirit/body does not have a future in our global reality. This understanding should lead us to seek holistic ministries which embody tangible ways of bringing transformation to lives and communities. “In the coming years, respect and relevance will flow to the global church when it does what it was created to do: to fill gaping holes, both spiritual and physical, in the lives of unnoticed, unwanted people. This is the heart language of the next generation, non-Christians and Christians alike.”4

Mutuality: Christian leaders from traditionally poor countries have much to offer and will demand to be heard. In reality, they must be heard. The Western church can no longer dominate and expect to be the ruling class of the church. The Spirit of Jesus is calling us to break from our colonial roots and treat those without money and power as equals in the mission of God. “Like Jesus, we need to open ourselves to people without education, wealth, or contacts, and we must not seek power in order to ensure that ministry is done on our terms. Mutuality requires concessions and intentionality on the parts of all players, and this is especially difficult for the people with a voice and access to power.”5 Mutuality requires the Western churches to take on the role of learners.

Migration: Modern migration is constantly in the news and will continue to be on the rise as people flock to different regions or cities of the world. While immigrants are escaping war, persecution, hunger, or poverty or whether they are seeking jobs, schooling, or a different lifestyle, we will always have the opportunities and challenges posed by migration. Immigration assures that around the globe Christian missions will be faced with radically diverse audiences. We will need strategies that can reach diverse people groups without requiring that they cross cultural barriers to experience Christian community. “Christians everywhere should reach their cities in order to reach the world. Even geographically stationary people are profoundly impacted by migration, as the world is coming to them.”6

Monoculture: The cultures of all countries will become more and more similar through technologically and economically driven forces. Worldwide images, ideas, celebrities, and ad campaigns homogenize all cultures under the influence of consumerism. Christians communicating with global neighbors will need to be aware that marketing from outside their borders now threatens to shape many of their deepest values. However, national leaders seek to balance their desire to maximize economic growth in their country with their desire to preserve indigenous cultures and traditions. Westerners are often seen as advocates of this threat of monoculturalism, which can negatively impact their missional influence.

Machines: The explosion of technology is transforming lifestyles around the globe. People are connecting in unprecedented ways through the internet, cell phones, television, and travel. The future global church must recognize both the “Jekyll and Hyde” aspects of the influence of technology in the lives and values of people in our world.

Mediation: There is much talk of the world’s flattening as well as the acceptance of diversity. However, in reality, our world is becoming more and more polarized. Small, divisive groups have more communication avenues for inciting discord and attracting sympathizers than ever before. The world church must find its role as a peacemaker who follows the example of the Prince of Peace by modeling and teaching a way of life that brings peace and unity in the midst of diversity.

Memory: Even though globalization has brought the world together in many respects, every nation or region has a distinct history that shapes their society. Yesterday continues to affect today. Our ancestors’ negative example of colonialism and control often go before us. These influences are often unspoken or unnoticed, yet they have incredible influence in interpersonal relationships. Western leaders must humble themselves, listen, learn, and even repent to overcome the walls that have been erected and maintained for years.

In addition to these seven global currents identified by Kling, at least one other current trend merits mention: the shift of the centers of Christianity. These centers have shifted radically from the West to the South and the East. Africa, Asia, and Latin America are becoming the epicenters of the Christian movement. No longer does world mission radiate from the Western world. In reality, mission is from everywhere to everywhere. Some of our counterparts in the Global South have more experience, greater maturity, and a clearer vision for a gospel movement in their own country and region of the world. In light of growing Christian leadership in the southern hemisphere, the role of the Western missionary is changing. Western missionaries must engage with international partners in a collaborative role to share Jesus with the unreached.

Of course, I am not able within the confines of this article to explore each one of these mission trends adequately. However, I will speak to three issues that are important to consider. They are best represented by three simple questions:

- How do we define mission?

- What is the good news we share?

- How do we fulfill our mission assignment within the context of our changing world?

Renewing a Holistic Mission

In an effort to recover the holistic nature of mission which has been present in Christian mission throughout its history, we must clearly define our mission. Do compassion and justice ministries count as mission work? Or is mission work only defined by gospel proclamation. Paul Borthwick writes, “Throughout the decades, the pendulum between preaching the gospel and concern for human need has swung widely. It takes on various terms—‘evangelism versus social action,’ or ‘the gospel in word versus the gospel in deed,’ or ‘preaching justification versus advocating justice.’ ”7 One extreme is fearful of the verbal proclamation of the good news. The other extreme favors the preached message of Jesus but leaves the care of human needs to other organizations. However, these pendulum swings may be calling us to find a biblical balance. Perhaps the answers are not found in one extreme or another. Perhaps it is not a matter of either/or, but rather a matter of both/and. This seems to be what Jesus was calling us to when he gave us what we call the Great Commission and the Great Commandment. The commission given by Jesus is to “go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you” (Matt 28:19–20). The commandment given by Jesus is to “love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind” and to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Matt 22:37, 39). One extreme leans only to the Great Commission, and the other extreme favors the discussion of the sheep and goats. “For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me” (Matt 25:35–36).

What is our Christian mission: serving or speaking? John Stott, in his classic book Christian Mission in the Modern World, updated and expanded by Christopher J. H. Wright, explores the relationship between missions as showing the gospel and missions as sharing the gospel.8 Stott proposes several ways we might attempt to reconcile this showing and sharing activity. Perhaps the ministry of compassion and justice is a means to disciple-making. In this view, the end result is winning people to Christ, and service is simply a means to the end. However, this approach is often exposed as a “bait and switch.” The bait is the service we provide, but the switch is exposed when our real intentions to make one a follower of Jesus become clear. This is an unhealthy view and actually leads to what is often referred to as rice Christians, those who come to Jesus only because of the food, services, or help provided. Stott explains that this is inevitable if we ourselves have been rice evangelists. “They caught the deception from us.”9 Perhaps, instead, social action is a manifestation of the gospel being proclaimed. In this view, giving to others is a natural expression of the good news we proclaim. Jesus demonstrates this truth in his words and work. This view is better, but it still makes service a subdivision of the sermon preached. Service can still become something given in order to obtain the desired end result and not the sole act of love. Stott discusses a third viewpoint that sees acts of compassion as a partner of evangelism. The two are partners yet stand alone and have their own means of expressing the love of Christ. Sharing the good news and showing the good news, word and action, and verbal proclamation and visible deeds are all a part of the mission of God and cannot be separated. For Stott they are like the two blades of a pair of scissors or the two wings of a bird. The link between proclaiming and serving is so close that they actually overlap. You can’t have one without the other. This is what we call a holistic gospel, good news that is actually concerned with the whole man or woman, including mind, body, and spirit. Scott sums up a holistic view of missions by saying:

We are sent into the world, like Jesus, to serve. For this is the natural expression of our love for our neighbors. We love. We go. We serve. And in this we have (or should have) no ulterior motive. True, the gospel lacks visibility if we merely preach it, and lacks credibility if we who preach it are interested only in souls and have no concern about the welfare of people’s bodies, situations and communities. Yet the reason for our acceptance of social responsibility is not primarily in order to give the gospel either a visibility or a credibility it would otherwise lack, but rather simple, uncomplicated compassion. Love has no need to justify itself. It merely expresses itself in service wherever it sees need.10

Sharing and showing, word and action, are all a part of the mission of God and cannot be separated.

Perhaps an integral view of the mission of God is best seen in the incarnation of Jesus. “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son…” (John 3:16). Mission is the action of God sending his Son and his people to speak and embody the good news of salvation, transformation, and the renewal of all things. The incarnation of Jesus becomes our model in missions. Paul describes the mission model of Jesus in Philippians. “Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ Jesus: Who being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself and became obedient to death—even death on a cross” (Phil 2:5–8). In the life of Jesus, God “became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). As we take on the life of Jesus in this world, this powerful act of incarnation becomes the perfect synthesis of the two sides of missions. Missions is the story of Jesus revealed in word and in flesh.

Therefore, this debate over compassion and justice ministries as opposed to evangelism ministries is an “old debate that needs to be put to rest.”11 A Christian’s friendship and care extended to another cannot save that individual. The good news of Jesus must be spoken, received, and obeyed. In the same manner, knowledge shared without the expression of the love of Christ is nothing more than a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal (1 Cor 13:1). Churches must engage all generations in a robust study and dialogue concerning the mission of the church. Great care should also be given to the selection of the mission efforts that reflect the church’s understanding of its mission. Greater dialogue and partnership needs to be opened between compassion and justice ministries and gospel movement ministries. Holistic mission is giving way to a deeper understanding of what is called integral missions.

Integration requires a “something” within which, or around which, everything is integrated. A human body has systems that are integrated around the person that exists. The integrating center that binds both compassion and evangelism is the good news of Jesus, the gospel. The gospel is the good news of all that God has done to save the world and establish the kingdom of God under Christ’s lordship. The gospel is the truth, the story, the facts of the saving acts of God. The importance of this understanding of the gospel is what leads us to the second significant issue that church leaders must engage. What is the good news we are sharing?

Reclaiming the Good News Message

For a church to engage the mission of God there must be clarity regarding the news that they are seeking to share with the world. Most Christians assume that when we say “gospel” we are all speaking the same language. Today, that is a false assumption. It is time for Christians to reclaim a more robust understanding of the gospel message of Jesus Christ. When we hear the term gospel many different thoughts may come to our mind. We may think of “gospel truth,” which in some cases has become a mammoth concept that encompasses all I believe to be truth that we must agree upon to be in fellowship with one another. We speak of “preaching the gospel,” which may be defined as teaching someone what they must do to be saved in order to make sure they reserve their place in heaven. When the apostles spoke of the gospel, they spoke of good news that was so good it had to be shared with the entire world.

N. T. Wright, in Simply Good News: Why the Gospel Is News and What Makes It Good,12 helps his readers explore a more hearty and biblical definition of the gospel. Wright describes four elements of the gospel. First, good news must be understood in light of its backstory. News takes place within a context of a longer running story that must be considered in order to understand why the news is good. Second, news is significant. It impacts lives and brings consequences that are meaningful. Because of what has happened, everything will be different. Third, the news unveils an exciting new future that lies ahead. It provides immediate joy now, but it also looks forward to the promises to come. Fourth, this news transforms the present moment and introduces an intermediate period of waiting. It places us in a location between the event that has happened and the future event that therefore will happen. “What good news regularly does, then, is to put a new event into an old story, point to a wonderful future hitherto out of reach, and so introduce a new period in which, instead of living a hopeless life, people are now waiting with excitement for what they know is on the way.”13 Wright contrasts this view of good news with what he sees taking place in many churches. Consider the good news we announce in our churches. Is it possible that it is not good news but rather just good advice? Listen carefully to the messages coming from our churches:

Here’s how to live, they say. Here’s how to pray. Here are techniques for helping you become a better Christian, a better person, a better wife or husband. And in particular, here’s how to make sure you’re on the right track for what happens after death. Take this advice. . . . You won’t go to hell; you’ll go to heaven. Here’s how to do it. This is advice, not news. The whole point of advice is to make you do something to get a desired result. Now, there’s nothing wrong with good advice. We all need it. But it isn’t the same thing as news. News is an announcement that something significant has happened.14

Are we sharing the powerful good news of Jesus or is our proclamation more focused on “the best way to live life?”

Paul reminds the Corinthian church of the gospel he preached to them. The same good news that they received and the same powerful story on which they had taken their stand. It is by this gospel they were saved. In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul defines this gospel or good news: “that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, and then to the Twelve” (1 Cor 15:3–5). The crucifixion and the resurrection of Jesus are the pivotal events that become defining moments in the good news that saves. “He was delivered over to death for our sins and was raised to life for our justification” (Rom 4:25).

Scot McKnight, in his book The King Jesus Gospel: The Original Good News Revisited, shares his belief that the word gospel has been hijacked by “the plan of salvation.” What we call “the plan of salvation” is, of course, vital to the good news we preach. However, it grows out of a powerful story, the biblical story of Israel and the story of Jesus. The biblical story from creation to Jesus is the saving story. Perhaps in reclaiming the gospel message we need to wrestle with McKnight’s premise that “equating the Plan of Salvation with either the Story of Israel or the Story of Jesus distorts the gospel and at times even ruins the Story.”15 McKnight suggests that if we see the fullness of the gospel in the Bible and we see how it was preached by the apostles, we will conclude that the gospel is “first of all, framed by Israel’s Story: the narration of the saving Story of Jesus—his life, his death, his resurrection, his exaltation, and his coming again—as the completion of the Story of Israel [Acts 2:22–35].”16 Second, he argues that the gospel centers on the lordship of Jesus. “Therefore, let all Israel be assured of this: God has made this Jesus, whom you crucified, both Lord and Christ” (Acts 2:36). The lordship of Christ provides a clear path to making disciples, because those who are disciples are under the lordship of Christ. Disciples are those who listen to the word of Jesus, obey, and follow him. Third, “gospeling” (as McKnight refers to what is typically called evangelism) involves calling people to respond. “Apostolic gospeling is incomplete until it lovingly but firmly summons those who hear the gospel to repentance, to faith in Jesus Christ, and to baptism.”17 Fourth, the gospel saves and redeems. The apostolic gospel promises forgiveness, the gift of God’s Holy Spirit, and justification. Three things happened in the death of Jesus. “Jesus died (1) with us (identification), (2) instead of us (representation and substitution), and (3) for us (incorporation into the life of God).”18 How does our evangelism today compare with the gospelizing of the apostles we see in the New Testament? Our gospeling must include the plan of salvation, but it is an incomplete gospel if it is not also a fuller discussion of the lordship of Jesus, his life, death, and resurrection, and the promise to come.

A reduction of the gospel that only focuses on salvation for a life after death or only on sin management is not the gospel presented by the apostles. Consider how a fuller view of the good news found in Jesus can shape our understanding of the previous question regarding the definition of mission. Is the gospel simply about salvation? Is it only about “going to heaven?” If so, then of course it has nothing to do with our life in this physical world and must be separated from any compassion and justice ministries. However, if the good news of Jesus Christ brings a kingdom message that transforms our lives both in the life to come and in the life we are living now, then we don’t need to separate compassion ministries and gospel ministries. Perhaps they are more clearly one and the same thing, two sides of the same coin.

As churches reclaim a biblical definition of the mission of God and rediscover why the news of Jesus is so good, they encounter a powerful motivation. Good news must be lived, and it must be shared! A clear and common understanding of the good news unites a congregation around a ground-breaking historical event that changes everything. Clarity regarding the gospel produces unity and provides a point of reference for our mission focus. It also helps determine the use of time and resources in missions. Cornelius Plantinga explains the impact of proper understanding of the gospel: the coming of the kingdom depends upon the coming of the King. The coming of the King means “that God’s righteousness will at last fill the earth, and that the real world in all its trouble and turmoil will be transformed by God’s shalom.”19

Good news must be lived, and it must be shared!

Reconsidering a Movement Methodology

Alan J. Roxburgh introduces a helpful concept in his book, The Missionary Congregation, Leadership, and Liminality.20 The author’s central thesis begins with the fact that the Christian church was at one point the center of Western culture yet has become marginalized and pushed to the edges of culture. Next, Roxburgh asserts that the culture itself in which the church exists is a decentered world. Thus both the church and the culture are in transition to something else, unknown. This has been rather obvious here in North America, however the majority world church has also been experiencing the same phenomenon and is just beginning to realize it. Roxburgh utilizes the work of Victor Turner regarding the function of liminality.21 He offers this framework as a model for the church to engage from a marginalized position in society. Typically, people and groups go through three stages in a rite of passage: separation—detachment from an established role in society; transition—an in-between state in which one is neither in the old group/situation nor the new group/position; and incorporation—the return of the individuals, having been transformed and changed, to a new place and status in society. Turner calls them separation, liminal, and reaggregation phases. The transition or liminal phase is a period of uncertainty and confusion in which the individual or group longs for release and a clear path to a new position. During this phase of transition, the church is tempted to reintegrate into a perceived cultural center, in other words, regain its place in society. However, this can lead to sacrificing the countercultural nature of the kingdom in an effort to adapt ourselves to modern culture. Roxburgh suggests that a helpful model is found in liminality; a better understanding of this transition phase enables the church to move into the position it needs to fill in our changing world.

If Roxburgh’s use of liminality is a model for engagement for the church today, it would benefit us to wrestle with the implications found in this transitional stage. “In this stage there are two critical elements: first, the negation of almost everything that has been considered normative, and second, the potential for transformation and new configurations of identity.”22 The church domestically and globally is experiencing this stage currently and in some cases has been there for some time. In this time of transition and confusion it is important to recognize a healthy tension at work. There is a need for the church to return to a stable, integrated order where its place and identity in this world is recognized and lived out. However, the tension comes when we realize that in some cases there is no returning to where the world was before, only movement into the future. Perhaps one practical mission discussion in which this principle applies is ecclesiology, the nature and structure of the church.

In some cases there is no returning to where the world was before, only movement into the future.

How did the number of Christians in the world grow from as few as 25,000 one hundred years after Christ’s death to up to 20 million in AD 310?23 How did the Chinese underground church grow from two million to over 100 million in 60 years despite considerable opposition? Of course, there are many factors at play in these questions. However, Alan Hirsch, in The Forgotten Ways, explores these questions and identifies six latent potencies in God’s people that lie dormant and forgotten until something catalytic prompts their rediscovery. He describes them as the centrality and lordship of Jesus, disciple making, the missional-incarnational impulse, organic systems, apostolic environment, and communitas. The sixth of these deserves special attention. Hirsch uses the word communitas to denote a community formed in a situation of significant ordeal and/or mission. It can be defined as the very spirit of community; an intense community spirit, the feeling of great equality, solidarity, and togetherness often formed through persecution or the call to a higher mission. Such communities are more organic than organizational in structure. These communities of faith create an environment in which Jesus is Lord, the spiritual gifts of each disciple are accessed for the benefit of the group’s mission, and the community has a clear mission and purpose. Communities of disciples who understand their nature and identity recognize that even from their marginalized position in society, they are to engage their world with the good news of Jesus. The life Jesus describes in the Sermon on the Mount illustrates the impact of the church as communitas:

You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again? It is no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot. You are the light of the world. A town built on a hill cannot be hidden. Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. In the same way, let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven. (Matt 5:13–16)

One church I am coaching through a process of renewing their mission ministry has determined that they need to define church from a biblical perspective. They have had a Western view of what church must look like and have imposed this view on their missionaries in other cultures. Mission leaders must redefine the life and work of the church from a biblical perspective.

Reclaiming the mission of the church, the good news we share, and the nature of the church in gospel movements provides a common and biblical foundation for churches to address the more pragmatic questions that we are tempted to answer first. Some of these questions are: How do we create an environment for a movement of disciple making in various regions of the world? What is the role of American churches in our changing mission landscape? How do churches respond to the phenomenon of immigration that is bringing the world to our doorstep and the unreached to locations where they can be more easily reached with good news? These and other pressing questions can be more faithfully addressed when we have a clear understanding and commitment to our mission, our message, and the method through which God has chosen to declare his glory, his Spirit working through his people, the church.

A Framework for Joining God in His Mission

Mission leaders must face these current issues as well as many others with honesty, humility, and courage. Only when we possess the Spirit of Jesus can we take the faithful steps to reimagine how we will engage our new reality. Church leaders are searching for ways to move forward in today’s changing mission landscape, yet what some are missing is a framework or a map to guide them on this journey.

How can churches develop a passion and process for local and global missions? There is not one simple answer to that question, but somehow we instinctively know that we must begin to think more like missionaries, both at home and abroad. We are living in the world’s third largest mission field here in the United States, with multiple nationalities represented in our communities. Culture, language, and worldviews have changed drastically around us. We are called to be “salt and light” in our own backyard! Churches have often ignored the undeniable connection between what they do on their local mission field and what they do with mission partners on a foreign field. I once had a conversation with a missionary who had grown up within the Churches of Christ and had experienced the best mission training that we have to offer. After several frustrating years on a difficult foreign field he made the statement, “I was sent here to make disciples, and I am just now realizing that I have never been discipled myself.” Is it fair for us to require the same thing of our sending churches that we are requiring of our mission churches? Perhaps we need to submit ourselves to some of the same training we expect our missionaries to experience, so that we can be on mission at home and more effective in stewarding our mission efforts abroad.

At Missions Resource Network (MRN) we have responded to these challenges by recalibrating our mission team training to fit local church needs. Most mission education involves developing five capacities within missionaries:

- A Theology of Missions – our mission is rooted in the nature of God. A proper theology establishes a solid biblical foundation on knowing God and his mission.

- A Strategy for Spiritual Formation – mission is not primarily a strategic undertaking. It is a spiritual endeavor. As followers of Jesus we must be continually transformed and conformed to the likeness of God’s son. Our mission is to glorify God, save the lost, and be transformed as disciples.

- Cultural Awareness – missionaries must understand and adapt to various cultural contexts as they share the never-changing good news of Jesus.

- Skills in Team Building – good one-another relationships are essential in living out the mission of God in any environment.

- Strategic Preparation – our strategic plans must focus on joining God in God’s mission and fulfilling our partnership role.

Our churches must develop each of these areas in their respective congregational culture as they seek to honor the great commission within their local and global contexts.

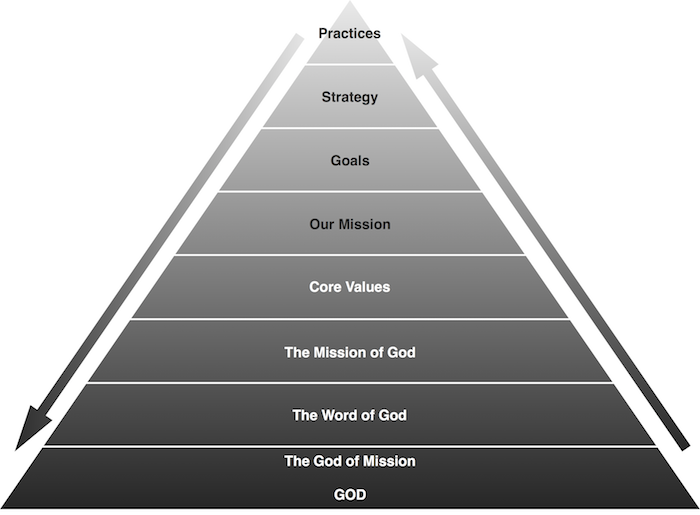

To help churches develop these capacities, MRN equips and coaches both domestic and foreign congregations through a process of discovery. For this journey, we provide a framework to guide in the development of what we call “a God-directed ministry.” This tool, in the form of a pyramid below, serves as a track for churches to run on in their quest to engage the mission of God. Most churches seeking to become more focused on domestic and foreign missions want to start at the top of this pyramid by changing their practices. They search out the best practices, often reproducing a model from a successful church, which was developed for a particular community of faith, in a particular location with a unique environment. They tend to slowly work down the left side of the pyramid without the foundation and power only provided by God. They develop their plan, find justification in Scripture, and then ask God to “bless” what they have planned. In reality, they work backward.

Figure 1: A God-Directed Ministry

Figure 1: A God-Directed Ministry

Instead, churches should start at the bottom of the pyramid by developing a theology of missions rooted in the nature of God. They must go back to the word of God to re-examine the mission of God, the gospel, and the role of the church. As they rediscover the mission of God, they then commit to living out the values that grow from this biblical understanding. Once this is underway, they are in a position to discern and articulate their mission calling based upon their location, resources, and experiences. When a church has a clear understanding of its mission, it can set measurable goals. Then, it can proactively determine what strategies and practices should be implemented, as well as select partners with whom it should work. If we lay a solid foundation for our mission rooted in the nature and identity of God and his mission, we are better equipped to discern God’s call for our church. We then can follow God more faithfully by joining him with steps of faith and obedience. Notice that it is not a linear process but an ongoing learning process as we move from Scripture to reflection to practice and back. This process has provided the framework for decision-making and forward movement for many churches seeking to experience the mission of God.

Conclusion

We are living in exciting times for God’s global mission. The good news is that God has been working around and through us in the last century in ways that have created a new reality. The challenging news is that a combination of international forces has created a new global mission landscape. We must wake up to the fact that we are missionaries here in North America. We are also not the saviors of the world. God has servants all over the world through whom he will do his best work. Our role is now that of a servant who joins what God is already doing. That means we need to exercise less control and exhibit more trust. It means we need to listen more and talk less. Finally, it means that we have to go back and develop a missiological foundation which will support our work in our local contexts as well as in our global partnerships. We cannot take things for granted any longer. This is a new world, and we have a lot of rethinking and development to do if we are going to be faithful stewards of the gospel in the twenty-first century.

Jay Jarboe is VP of Ministry Operations and Director for Church Equipping at Missions Resource Network (MRN), a global network equipping the body of Christ to make disciples worldwide. Before joining the ministry of MRN, Jay served as the Lead Minister for the Sunset Church of Christ in Lubbock, Texas. During his 25-year ministry with the Sunset Church of Christ and Sunset International Bible Institute (SIBI), Jay served as the Director of the Adventures in Missions (AIM) program, an apprentice missionary training program, and as the Dean of Missions and an instructor at SIBI. He is married to Sherry, and they have two grown children, Meagan and Ryan. Jay and Sherry were missionaries in Mexico City for six years. Sherry works as the Mission Site Coordinator for Let’s Start Talking, a ministry that sends out hundreds of Christians around the globe to share their lives and Jesus by reading the Bible with those seeking to improve their English. Jay holds a BA from Texas Tech University and a Masters in Missions and a Master of Divinity equivalency from Abilene Christian University. Jay has worked with churches, missionaries, and mission leaders on six continents. He coaches, mentors, and equips servant leaders for mission, transformation, and multiplication. His passion is seeking to be transformed into the image of Christ and helping others in that same quest.

1 Scripture quotations are from the New International Version.

2 Fritz Kling, The Meeting of the Waters: 7 Global Currents that Will Propel the Future Church (Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook, 2010).

3 Ibid., 32.

4 Ibid., 42.

5 Ibid., 72.

6 Ibid., 102.

7 Paul Borthwick, Great Commission, Great Compassion: Following Jesus and Loving the World (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2015), 16.

8 John Stott and Christopher J. H. Wright, Christian Mission in the Modern World, updated and exp. ed. (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2015).

9 Ibid., 25.

10 Ibid., 29.

11 Femi Adeleye, lecture given at a gathering of FOCUS-Kenya Associates in Mombasa, Kenya, March 2002; quoted in Borthwick, 16.

12 N. T. Wright, Simply Good News: Why the Gospel Is News and What Makes It Good (New York: HarperCollins, 2015).

13 Ibid., 4.

14 Ibid., 5.

15 Scot McKnight, The King Jesus Gospel: The Original Good News Revisited (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 37.

16 Ibid., 132.

17 Ibid., 133.

18 Ibid., 51.

19 Cornelius Plantinga, Engaging God’s World: A Christian Vision of Faith, Learning, and Living (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 142.

20 Alan J. Roxburgh, The Missionary Congregation, Leadership, and Liminality, Christian Mission & Modern Culture (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity, 1997).

21 Victor Turner, “Liminality and Communitas,” in The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, (Chicago: Aldine, 1969), 94–113, 125–130.

22 Roxburgh, 29.

23 Alan Hirsch, The Forgotten Ways: Reactivating the Missional Church (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2006), 18.