The emergence of the concept of missio Dei amid the struggles of Christian world missions in the mid-Twentieth Century occasioned a theological paradigm shift. Although its conceptualization has been contested and sometimes dichotomized, recent developments move toward a broad, integrative vision of God’s mission that may serve as the best framework for the church’s theology and praxis.

Rediscovering Missio Dei

Everything is mission. On the lips of a “career missionary,” those words seem far too self-involved to be true, or even moderately insightful. As a summary of the implications drawn from sixty years of ecumenical reflection on the sending of the Son and the Spirit, however, they are a legitimate challenge to every corner of Christianity to understand the world, the church, and Scripture in terms of missio Dei1—God’s mission. In order to understand how missio Dei came to be a theological concept currently discussed on a broad popular level, we must enter a historical world that will be foreign territory for many readers. In so doing we may gain a clearer understanding of what is at stake theologically in the debate over terminology, which seems at first glance to be blown out of proportion. Our entry point into that world is a village in Germany called Willingen.

The ecumenical gathering of church leaders known as the International Missionary Council held its 1952 meeting in Willingen. Two immediate crises set the stage for the meeting. First, Mao Tse-tung closed China, removing all foreign missionaries. Naturally, this caused distress among these leaders, committed as they were to the spread of gospel among such a significant portion of the human population. Second, the realization was dawning that Christian missions had been deeply implicated in the colonialist project of Western civilization, a project that was beginning to crumble. Missions had been tied to the spread of Enlightenment culture, and the churches influenced by these ecumenical leaders were about to begin a long and painful struggle to differentiate their mission work—its motivations, means, and goals—from colonialism.

It is also necessary to mention a third looming specter. Colonialism aside, critical self-reflection also revealed that Christian missions was plagued by what would come to be called ecclesiocentrism. What the church expected to achieve in its missions was, through and through, too much about the church. We might characterize (or caricature) the worst of ecclesiocentrism this way: The church sends the church’s missionaries to accomplish the church’s mission, which is the expansion of the church and, implicitly, the achievement of the church’s agenda.

Willingen was host to a broad range of theological dispositions, but two polarized positions, which I will refer to as traditionalist and humanist, emerged as the dominant contenders battling over the conceptualization of missio Dei in the last century. Though they became two seemingly mutually exclusive options well after Willingen, they were not obviously diametric opposites at the conference itself. In fact, they were similar enough in their response to the problems mentioned above that participants managed to draft a unifying statement at conference end. Moreover, I will argue below that the currently emerging concept of missio Dei is a healthier blending of these two positions than many would have thought possible in the decades following Willingen.

The traditionalist position was traditional in that while it retreated from the paternalism and ecclesiocentrism of the past, it still maintained that the church was the means to the fulfillment of God’s eschatological intentions. For the traditionalist, therefore, missio Dei signified a move toward chastened self-perception by way of theocentrism. The church was freshly recognized as, we might say, merely the means, whereas God was the ultimate source, actor, and fulfiller of mission.

The humanist view did not immediately deemphasize the church’s role, though more radical elements were already present at Willingen. Instead, it focused upon a more realized eschatology, maintaining that God had already inaugurated his kingdom. The church, then, served not as means to its realization but as proclaimer of its reality.2 Dutch missiologist Johannes Christiaan Hoekendijk developed this line of thinking further. His essential argument was that because the realization of the kingdom in the world is God’s doing, and because the church is not a means to an unrealized eschatological reality, the reasonable conclusion is that mission is God’s work in the world regardless of (and, as history would suggest, often despite) the church. Thus, the humanist perspective became preoccupied with God’s work in the world apart from the church, which proponents naturally understood in terms of humanity’s socio-political concerns.

Though clearly at odds, the traditionalist and humanist views hung together on one major point of agreement: “Mission is ultimately God’s affair.”3 The expression of this fact in terms of “missio Dei” seems especially shaped by the theology of Karl Barth, who first revived the trinitarian idea of missio in 1932.4 In addition, the preliminary report from the U.S. study group hinged upon the doctrine of the Trinity. Thus, the statement that ultimately distills the conference findings reads:

The missionary movement of which we are a part has its source in the Triune God Himself. Out of the depths of His love for us, the Father has sent forth His own beloved Son to reconcile all things to Himself. . . . On the foundation of this accomplished work God has sent forth His Spirit, the Spirit of Jesus. . . . We who have been chosen in Christ . . . are by these very facts committed to full participation in His redeeming mission to the world. There is no participation in Christ without participation in His mission to the world. That by which the Church receives its existence is that by which it is also given its world-mission. “As the Father hath sent Me, even so send I you.”5

It was another document, written by Karl Hartenstein after the conference, that utilized the Latin phrase missio Dei in order to summarize the fundamental idea conveyed by the conference findings:

Mission is not just the conversion of the individual, nor just obedience to the word of the Lord, nor just the obligation to gather the church. It is the taking part in the sending of the Son, the missio Dei, with the holistic aim of establishing Christ’s rule over all redeemed creation.6

Hartenstein clearly wrote from a traditionalist perspective, though his terminology would also be co-opted by the humanist camp in order to signify an idea of mission exclusive of the church’s “taking part” in God’s movement toward the world. Yet, we may note that the dispute was not simply between those who advocated a “social gospel” and those who did not. The “holistic” notion of a kingdom over “all redeemed creation” was integral to the traditionalist view, which made room also for individual conversion, obedience to the word, and the gathering of the church. The issue remained, implicitly at least, one of eschatology and its implications for the church’s instrumentality. That is to say, a critical dialog between eschatology and ecclesiology had begun.7

Considering the concept from another angle, the intersection of trinitarian thought and salvation history was also a major variable for the alternative views of missio Dei. As Hartenstein indicates, the traditionalist view understood the “sending” of Son (and Spirit) to be constitutive of mission. It is that particular salvation-historical datum that qualifies the concept of missio Dei. In contrast, while movement within the Trinity was also basic for the humanist perspective, it was abstracted from the confines of salvation-history.8 According to this understanding, intra-trinitarian movement (missio Dei) continues in the world quite regardless of the particular sendings of Jesus recorded in the Gospels or of the Spirit experienced in the church. Moreover, despite trinitarian language in the humanist camp, without reference to the salvation-historical narrative of Jesus and the Spirit, missio “devolved into an immanent principle of world history” focused on “being, not God’s being” (emphasis original).9 At stake in this convergence of salvation history and Trinity is, again, one’s understanding of the kingdom. Is the establishment of the kingdom that Jesus announced a work that God does in world history apart from the proclamation of Jesus by the church and the power of the Spirit manifest in the church? An affirmative answer caused many to see the socio-political shifts toward a “better” (more humanitarian) world as proper to the concept of missio Dei.

At the risk of oversimplification, these basic observations lay a minimum of groundwork for considering some of the implications that this monumental shift within Western theology entailed. Because the rediscovery of missio Dei is still causing aftershocks in theology and missiology today, tracing the path of these implications will bring us to consider insights that are only now emerging.

In the Wake of Willingen: Implications of the Shift

Relief was the most immediate payoff of recasting missions in terms of missio Dei.10 If the mission is fundamentally God’s, then the church’s failures (e.g., colonialism, ecclesiocentrism) and limitations (e.g., the closure of China) were not cause for despair. Even if, as traditionalists affirmed, the church is instrumental in God’s completion of his mission, it remains God who will complete it. Not only the justification for but also the viability of mission rests upon the sovereignty of God, even in the midst of terribly uncertain circumstances. To cast it more starkly, God’s mission cannot be compromised even when the church is.

A terminological evolution also occurred in the wake of Willingen, and its subtlety continues to beleaguer missiology today. Many began to reserve “mission” for reference to missio Dei and coined “missions” (note the added -s) for the church’s missionary endeavors. The distinction served to express differing concerns, depending on one’s understanding of missio Dei, but for all involved in the conversation it was a necessary result of missio Dei’s conceptualization. Thus, more than merely an antidote for anxiety, missio Dei was a corrective for both colonialism and ecclesiocentrism. “It is inconceivable that we could again revert to a narrow, ecclesiocentric view of mission.”11 As the mission is God’s, God’s agenda is determinative rather than that of colonialism, the church, or anything else. Theocentric missions is the upshot, with the church’s continual self-assessment the corollary. In light of missio Dei, the vital question for churches becomes: Are we on board with God’s mission in any given endeavor, or are we just calling it missions?

Critics have relentlessly leveled one charge in particular against advocates’ lofty claims for missio Dei: “If everything is mission, nothing is mission.”12 There are two different uses of this well-worm adage, and both call to attention important implications for the conceptualization of missio Dei.

First, missio Dei seems to imply an ontological assertion: God is missionary in nature. The corollary is therefore that everything God does is mission. Beyond the fear that this entails a “humanistic” or “social” gospel a la Hoekendijk, the problem with everything being mission is that it “necessarily makes light work of the distinction that Christian theology, because it is rooted in church members’ experience of God, has to make between the incomprehensible activity of God in the world and the redeeming and healing activity of Jesus Christ.”13 Putting it this way, God is admittedly “doing” much more than the salvation-historically limited activity of Jesus and the Spirit in the church. The complaint is therefore semantic: because of the experiential (i.e., epistemological) difference between what are usually called “sustaining” activity and “saving” activity, there is legitimate need to distinguish between the two in our God-talk.

In other words, if God’s “missionary nature” requires that we call everything he does from providence to personal salvation “mission,” what word then will we use for the activity traditionally designated as mission? Of course, this objection does not actually deny that we ought theologically to understand all of God’s activity in terms of his revealed activity (the sending of the Son). Rather, it is a caution against ascribing to God through the label “mission” a variety of activities that are not known to be God’s doing in the same way that God’s people know their own experiences to be his doing.

Second, if everything God does is mission, then mission becomes the proper descriptor of everything the church does in participation with him. “Mission” effectively becomes synonymous with “ministry.” Therefore, many object to the idea that “everything is mission” in reference to the church’s activity. Tormod Engelsviken is representative:

It takes some courage to limit or restrict both the biblical basis and the theological understanding of mission, as well as the practical outworking of it to what is the specifically missionary “intention,” without denying the missionary “dimension” (to borrow the famous words of Lesslie Newbigin) of all the church is doing.14

This seems like another semantic grievance, however, if we are willing to admit that all Christian ministry (“all the church is doing”) has a missionary “dimension” by virtue of its relationship to all that God is doing. Although it is frustrating to our established linguistic compartmentalization, the “discovery” of missio Dei calls the church to speak about all that God does and all that the people of God do in participation with him in terms of the sending of Son and Spirit.

Indeed, the generalization of mission as a theological category was inevitable, for while the conceptualization of missio Dei occurred in the context of classically “missionary” concerns, its trinitarian basis meant that a shift necessarily occurred in theology proper rather than in missiology alone. That is to say, what is true of cross-cultural church work because it is true of God must also be true of every other church work. Whatever we are doing, we are merely participants in what God is doing. If this principle is true, the essential question remains: Is everything God is doing revealed paradigmatically in the missio of Son and Spirit? If so, we can hardly speak wrongly of everything God and the church do by calling it mission.

In contrast to the usual objection, Wolfgang Günther states:

[Missio Dei] offers an umbrella, as it were, under which all the different biblical motives for mission and the corresponding different directions in our churches have their rightful place but are at the same time relativized. God’s mission is so all encompassing that all who take part in it can only ever take up one small part of it.15

These words are reminiscent of David Bosch, the theologian who spelled out the implications of missio Dei for evangelical Christianity in his landmark work, Transforming Mission:

We do need a more radical and comprehensive hermeneutic of mission. In attempting to do this we may perhaps move close to viewing everything as mission, but that is a risk we will have to take. Mission is a multifaceted ministry, in respect of witness, service, justice, healing, reconciliation, liberation, peace, evangelism, fellowship, church planting, contextualization, and much more. And yet, even the attempt to list some dimensions of mission is fraught with danger, because it again suggests that we can define what is infinite. Whoever we are, we are tempted to incarcerate the missio Dei in the narrow confines of our own predilections, thereby of necessity reverting to one-sidedness and reductionism. We should beware of any attempt at delineating mission too sharply.16

It was indeed a risk that Bosch took, in that he dared to accept what missio Dei meant for the nature of the whole church itself: “There is church because there is mission,”17 “it is the missio Dei which constitutes the church,”18 and ultimately, therefore, “Christianity is missionary by its very nature, or it denies its very raison d’être.”19 It follows, then, that we should call all that the church does “mission,” regardless of the risk of misuse it entails or the change of vocabulary it requires.

The shift in theology proper continues to reverberate through the theological disciplines. These aftershocks are proving extremely generative and, reciprocally, refining the concept of missio Dei. As Bosch indicated, ecclesiology was foremost among the fields forever changed for those who would accept the implications of missio Dei. The widespread acceptance that the church, by virtue of missio Dei, is missionary in its very nature has led to a fundamental reorientation of the church’s self-understanding, its motives for participation in mission, and its view of the gospel vis-à-vis the kingdom message of Jesus. This has found expression in the “missional church” movement, which requires a brief explanation of the semantic evolution that produced the term “missional.” Darrell Guder, one of the leading missional church thinkers, explains:

This terminological experimentation is, to be sure, driven by all that we have learned in the twentieth century as we became more aware that the Christian movement was in fact a global reality, a “world missionary community” (Mackay). Understanding this “great new fact of our time” has encouraged the gradual shift away from ecclesial thinking that centers upon the church, especially the Western church, as an end in itself, and instead toward understanding the identity and purpose of the church within God’s mission, subordinate to and focused upon God’s purposes. The term “missional” was introduced in order to foster this more radical way of thinking about the church and, more generally, of doing theology. It was, as we stated in the Gospel and Our Culture network’s research project published in 1998, an attempt to unpack the operative assumption that “the church is missionary in its very nature.”20

Guder notes that the term has begun to suffer a fate similar to “missio Dei” regarding its overuse and subsequent vacuousness. Moreover, “missional” has become “a cliché, a buzz word” in pop Christianity, further diminishing the value of the word for many.21 In fact, that is a problem that confronts the entire missional church movement, as its impulse toward contextualization has caused it to be lumped together with the “emergent church” phenomenon. For many who so freely sling these labels about, “missional” and “emergent” seem merely to connote a culturally relevant or, less flatteringly, a “cool” way to be the church.22

Still, “missional” appears to have finally filled the terminological void over which the semantic arguments above languished. That is to say, the adjective “missional” denotes the “dimension” of the entire church that corresponds to the missio Dei, leaving “missionary” for the properly “sending” activity (“intention”) of the church. More generally, missional is “simply an adjective denoting something that is related to or characterized by mission, or has the qualities, attributes or dynamics of mission. Missional is to the word mission what covenantal is to covenant, or fictional to fiction” (emphasis original).23 Given this development, we might now rather say that God is missional in nature, and therefore the church is missional in nature, reserving missionary for the persons and activities related to the church’s particular sendings.

In any event, the missional church movement is one of the most prominent aftereffects of missio Dei’s rise. In essence, it is the outworking of what it means for a congregation to be sent as the Son was sent in its context, apart from the issue of sending missionaries to other contexts. Ecclesiology has taken a turn for the participatory, thereby challenging ever greater numbers of the church’s members to consider what being a part of this missional body means for their own lives. Becoming part of a church as an end in itself is, thankfully, a dying model in many corners.

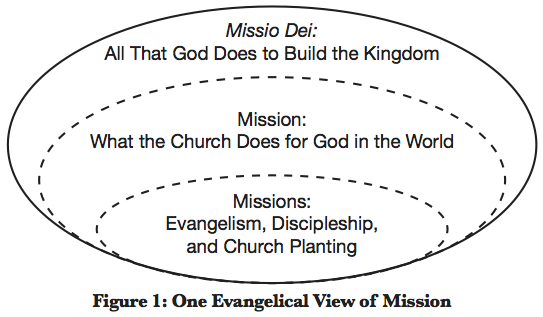

All of this church-talk is naturally taking place within the traditionalist vein of the earlier dichotomy. Church is a working assumption in the ongoing conversation. Sadly, the Church Growth Movement that rose to prominence among traditionalists, in part as a reaction to the secularizing trends of the humanist vein, stayed disconcertingly close to ecclesiocentrism.24 Yet, missional church thinkers represent a long-overdue, grassroots re-convergence of traditionalist and humanist concerns. Many churches have begun to advocate a vision of “shalom” or total well-being on a global, societal scale in conjunction with the church’s vital participation in God’s realization of that reality, which is called the kingdom of God. Figure 1, reproduced from a recent missions textbook,25 is indicative of the way in which evangelical theology is currently resolving the tension between the narrow, traditional use of “mission” on one hand and the somewhat novel understanding of God’s extra-ecclesial work in terms of “mission” on the other.

This represents a critical shift from a dialectic to a synthetic understanding of missio Dei, progress beyond the initial conflict that stood at the heart of the formula. While a holistic understanding of missio Dei was present in embryonic form in the theology of many Willingen participants, the dichotomy that emerged subsequently between traditionalists and humanists prevented its acceptance on a broad scale. We are now beginning to see a church-wide discovery of the whole mission of God, exemplified in Jesus’ total witness to the in-breaking reality of the kingdom.

Another potentially monumental shift is evident in the current discussions of missio Dei. It is a move to a substantive teleology, signaling a step beyond the early intersections of ecclesiology with eschatology and salvation-history with Trinity. This shift is reflected in a subtle, albeit natural, change in the usage of “mission” in English-language missiological discussion, which echoes broad cultural usage of the term:

Many organizations talk about their mission. There are missions to explore space, diplomatic missions, mission statements of businesses, and fact-finding missions. All of these rely on the core idea of mission—the sending of someone or something to do a job.26

While many have explained mission in terms of an over-simplified etymological notion of “sending,” the emerging sense of mission in contemporary usage is focused on the purpose, goal, or aim—in short, the telos—that drives the sending. It has been common to refer to “God’s purposes” in the discussion of missio Dei. For instance, Hartenstein’s initial formulation cited above refers explicitly to the “holistic aim” of participation in the sending of the Son; a conceptual union of Trinity and telos. Recently, however, teleology is becoming constitutive of the meaning of the missio Dei itself. In other words, while the sending of the Son is still paradigmatic and determinative for mission, and while the historical conceptual development discussed above still stands behind today’s ubiquitous reference to “God’s mission,” the concept of missio Dei has broadened theologically beyond discussion of the Trinity.27 This is distinct, however, from the humanist camp’s abstraction of “sending” from the Gospel accounts in order to generalize it as a universal principle. It is, instead, a theological reflection upon the reason for the sending of the Son—that which stands behind and fuels the mission. In summary, to speak of the missio Dei is to denote its purpose.

In a way, the movement to a less exclusively trinitarian idea of God’s mission is an echo of the much-debated historical discord between the formal disciplines of Biblical and Systematic Theology. Mission seems to have presented itself as a contender for the ever-elusive “center” that Biblical Theology seeks, yet it is with tremendous difficulty that Trinity, the pinnacle of Systematic thought, should serve as such.28 The purpose manifest in missio Dei, however, is proving most promising. Thus, Christopher J. H. Wright’s watershed work, The Mission of God, puts mission to work for Biblical Theology, contending that the biblical narrative’s “whole worldview is predicated on teleological monotheism” (emphasis added).29 “The Bible presents to us a portrait of God that is unquestionably purposeful,” says Wright, and mission is best understood as “a long-term purpose or goal that is to be achieved through proximate objectives and planned actions.”30

On this basis, Wright sets out to develop and employ a “missional hermeneutic,” which is the latest significant upshot of missio Dei.31 While Wright’s is the first major monograph on the subject, he is notably preceded by Richard Baukham’s outline of a mission-centered narrative hermeneutic, which has a substructure justifiably described as teleological, in that “a metanarrative of this kind has a definite future goal towards which it moves.”32 These attempts at constructing a missional hermeneutic are merely another manifestation of the affirmation that “everything is mission.” If mission is an adequate conceptual category for all God’s activity, it naturally follows that we may read the entire narrative of Scripture through the lens of God’s purposeful movement toward his ends. Moreover, “missional” becomes the descriptor for the framework that holds together all the theological disciplines in proper relation to God’s agenda, which ultimately gives them their significance and which they serve.33

A teleological definition of mission naturally raises the question of what God’s telos is. Even assuming that “the kingdom” is the goal, as much of the literature appears to do, our subsequent description of the kingdom continues to be subject to a variety of interpretations, as it was from the beginning of missio Dei’s emergence. But this is not the place to begin exploring the many possible articulations of God’s purposes for the world. For now, suffice it to note this most recent step in the conceptual evolution of missio Dei.

Conclusion

What began as a contextually driven search for answers has led to one of the most significant theological developments of our time. There are perhaps other concepts that could have functioned to recenter the church in a similar way. Yet, it was immersion into the global vision that world missions uniquely engenders that called the church to account in the middle of the last century. In that sense, the conceptualization of missio Dei is itself another affirmation that mission is the mother of theology.

It was the need to reconsider what it means to be sent as the Son was sent, in his way for his purposes, that afforded a renewed theocentrism, a chastened ecclesiology, and a reframing of “everything” in relation to God’s being and act revealed in the sending of Son and Spirit. Undoubtedly, whenever a single formula attempts to designate what “everything” is about there must be tremendous repercussions. Many will continue to feel that missio Dei and its adjectival neologism “missional” are too provincial, too entrenched in the special concerns of missiology, to provide an adequate framework for “everything.” In the ensuing dialogue about the adequacy of our words, it is vital to remember that terminology is not what is truly at stake. Rather, it is the need somehow to speak about the concepts that should shape Christianity’s very worldview. Our capacity to obfuscate essential theological tenets is undisputed; our tendency to see ourselves and our world wrongly, undeniable. Whatever words we choose, we must not fail to speak about who God is in light of the sending of Jesus and the Spirit and what that means for everything we are and do.

Glossary of Key Words

colonialism – n. (a) the expansion of influence from one society to another with the aim of control, whether by literal colonization or by political and cultural domination; (b) specifically referring to the expansion of Western civilization during the 18th-20th centuries

ecclesiocentrism – n. (a) literally, church-centeredness, i.e., the placement of primary importance upon the church; (b) in missiology, the view that Christian mission has its source, sustenance, and culmination in the church

eschatology – n. (a) the theological study of the “end” (eschaton), referring to the “last day” as envisioned in the biblical narrative; (b) realized eschatology refers to the realization, to one degree or another, of end events in the present time, as in the realization of the kingdom of God in human history

humanist view – n. in this paper, the perspective of those who understand missio Dei to refer to a principle of God’s action in the world without necessary reference to the sending of Son and Spirit, thus affording humanity’s social and political agendas preeminence in the description of God’s mission

missio Dei – n. (a) a Latin phrase literally translated as mission of God or sending of God, the meaning of which varies depending upon the theological disposition of the speaker; (b) originally, the sending of the Son and Spirit; (c) in other usage, the principle of God’s immediate involvement in the improvement of the human situation through secular political and historical processes; (d) in recent English usage, the purpose or goal of God

missional – adj. (a) describing something that is related to God’s mission in an essential way; (b) often connotes the corrective assertion that something should not be understood apart from God’s mission, as in “missional church”

missionary – n. (a) a sent person; (b) in traditional usage, a person sent to carry out the purposes of God or the church, usually cross-culturally; adj. (c) of or related to persons sent, as in “missionary endeavor”; (d) sometimes used synonymously with missional, where the notion of being sent in the usual sense is absent, as in “the church is missionary is it very nature”

missions – n. (a) the church’s work of “sending,” whether near or far, for the purpose of participation in God’s mission, synonymous with mission work, as in “domestic missions” or “domestic mission work”; (b) sometimes synonymous with missio ecclesiae, a Latin phrase literally translated as mission of the church, which denotes the categorical difference between the church’s activity and God’s activity; (c) sometimes reserved for particular activities such as evangelization and church planting

salvation history – n. (a) a concept developed in Biblical Theology to express the relationship between secular history and history as the Bible tells it in terms of God’s saving acts; (b) denotes the continuous, epochal account of God’s work in history understood by virtue of particular moments of redemption or revelation recorded in the Bible; (c) functionally synonymous with postmodern usage of “biblical narrative” or “metanarrative,” which express a unified story not in terms of modernist “history” but in terms of a worldview that places all history in relation to its particular epistemological claims

teleology – n. (a) the theological study of purpose (telos); (b) specifically, the study of the purposes of God, especially in relation to his mission

theocentrism – n. (a) literally, God-centeredness, i.e., the placement of primary importance upon God; (b) in missiology, the view that Christian mission has its source, sustenance, and culmination in God

traditionalist view – n. in this paper, the perspective of those who understand missio Dei to define mission as particularly God’s, though never without reference to the church’s participation in that mission, thus maintaining the church’s traditional instrumentality

Greg McKinzie (http://gregandmeg.net/greg) is a missionary in Arequipa, Peru, where he partners in holistic evangelism with Team Arequipa (http://teamarequipa.net) and The Christian Urban Development Association (http://cudaperu.org). He is a graduate (MDiv) of Harding Graduate School of Religion. He can be contacted at gemckinzie@gmail.com.

Bibliography

Ahonen, Tiina. “Antedating Missional Church: David Bosch’s Views on the Missionary Nature of the Church and on the Missionary Structure of the Congregation.” Swedish Missiological Themes 92, no. 4 (2004): 573-89.

Bauckham, Richard. Bible and Mission: Christian Witness in a Postmodern World. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003.

Bosch, David J. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. American Society of Missiology Series 16. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1991.

Engelsviken, Tormod. “Missio Dei: The Understanding and Misunderstanding of a Theological Concept in European Churches and Missiology.” International Review of Mission 92, no. 367 (October 2003): 481-97.

Flett, John G. “Missio Dei: A Trinitarian Envisioning of a Non-Trinitarian Theme.” Missiology: An International Review 37, no. 1 (January 2009): 5-18.

Gospel and Our Culture Network. “eSeries No. 2.” The Gospel and Our Culture. http://www.gocn.org/resources/newsletters/2009/01/gospel-and-our-culture.

Guder, Darrell. “Missio Dei: Integrating Theological Formation for Apostolic Vocation.” Missiology: An International Reiview 37, no. 1 (2009): 63-74.

Günther, Wolfgang. “The History and Significance of the World Mission Conferences in the 20th Century.” International Review of Mission 92, no. 367 (October 2003): 521-37.

Kinnamon, Michael and Brian E. Cope. The Ecumenical Movement: An Anthology of Key Texts and Voices. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997.

Moreau, A. Scott, Gary R. Corwin, and Gary B. McGee. Introducing World Missions: A Biblical Historical and Practical Survey. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004.

Neill, Stephen. Creative Tension. London: Edinburgh House Press, 1959.

Richebächer, Wilhelm. “Missio Dei: The Basis of Mission Theology or a Wrong Path?” International Review of Mission 92, no. 367 (October 2003): 588-605.

Wright, Christopher J. H. The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2006.

1 Bolded terms are defined in a glossary at the end of this article.

2 Wolfgang Günther, “The History and Significance of the World Mission Conferences in the 20th Century,” International Review of Mission 92, no. 367 (October 2003): 529.

3 Ibid.

4 Wilhelm Richebächer, “Missio Dei: The Basis of Mission Theology or a Wrong Path?” International Review of Mission 92, no. 367 (October 2003): 590.

5 Michael Kinnamon and Brian E. Cope, The Ecumenical Movement: An Anthology of Key Texts and Voices (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 339-40.

6 Quoted in Tormod Engelsviken, “Missio Dei: The Understanding and Misunderstanding of a Theological Concept in European Churches and Missiology,” International Review of Mission 92, no. 367 (October 2003): 482.

7 Tiina Ahonen, “Antedating Missional Church: David Bosch’s Views on the Missionary Nature of the Church and on the Missionary Structure of the Congregation,” Swedish Missiological Themes 92, no. 4 (2004): 576-77.

8 Ibid., 578-79.

9 John G. Flett, “Missio Dei: A Trinitarian Envisioning of a Non-Trinitarian Theme,” Missiology: An International Review 37, no. 1 (January 2009): 10.

10 Günther, 530.

11 David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission, American Society of Missiology Series 16 (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1991), 393.

12 Stephen Neill, Creative Tension (London: Edinburgh House Press, 1959), 81, quoted in Bosch, 511.

13 Richebächer, 591.

14 Engelsviken, 484.

15 Günther, 530.

16 Bosch, 512.

17 Ibid., 390.

18 Ibid., 519.

19 Ibid., 9.

20 Darrell Guder, “Missio Dei: Integrating Theological Formation for Apostolic Vocation,” Missiology: An International Review 37, no. 1 (2009): 65.

21 Ibid.

22 Such connotations are certainly not what the theological leadership of these movements intends.

23 Christopher J. H. Wright, The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2006), 24.

24 The history of the split between traditionalists and humanists as it played out in the International Missionary Council and other gatherings, the “moratorium” on missions among liberals, the emergence of the Church Growth Movement among conservatives, and many other pertinent concerns cannot be addressed fully in this brief introduction to the concept of missio Dei.

25 A. Scott Moreau et al., Introducing World Missions: A Biblical Historical and Practical Survey (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004), 73. This way of presenting the terminology is problematic for the simple reason that missio Dei is very often translated as “the mission of God” in English literature. It is confusing, therefore, to use “mission” exclusively for “what the church does.” Likewise, “missions” for many means simply “what the church does,” leaving no special terminology for “evangelism, discipleship, and church planting” over against other acts of witness and service. Yet, the impulse among conservatives to define missions only in terms of those three aspects is still strong, and we may understand the diagram as a helpful compromise. In any case, the authors are right when they say, “. . . at least for now among evangelical writers, knowing how a particular person uses a term is more important than knowing what the term means in the larger discipline of missiology” (ibid.).

26 Ibid., 71.

27 There is still a good deal of work being done vis-à-vis trinitarian theology, and it remains the necessary starting point for the conceptualization of missio Dei. See, e.g., Mark Love’s article in the present issue, which calls the trinitarian conceptualization of missio Dei into new territory. Nonetheless, a broadening has undoubtedly occurred, with the result that trinitarian theology is no longer the only realm in relation to which missio Dei is rightly defined.

28 Biblical Theologians often consider doctrinal formulations such as the Trinity to be suspect on the grounds that they are read into the text (particularly the Old Testament), preventing proper exegesis. In contrast, mission as an expression of the teleological shape of the whole biblical narrative seems to some to be more native to the text.

29 Wright, 64.

30 Ibid., 23.

31 E.g., see the important work being done on missional interpretation at the Gospel and Our Culture Network (http://www.gocn.org/resources/newsletters/2009/01/gospel-and-our-culture).

32 Richard Bauckham, Bible and Mission: Christian Witness in a Postmodern World (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003), 16.

33 Guder, 66-69.