Recent contributions to the development of missional hermeneutics are significant, though they indicate that a great deal of unexplored territory remains. This essay offers a model for plotting current themes and emphases among missional interlocutors, on which basis the author proposes an integration of key dimensions of missional theology. In conversation with current missional hermeneutical proposals, the author then develops five theses that signal a trajectory for revisioning the hermeneutical spiral.

Plotting Current Themes and Emphases in Missional Theology

The scholarly pursuit of a missional hermeneutic is presently beleaguered by the ambiguity of the term missional. This is not merely a matter of popular misappropriation; scholars’ diverse uses of missional also obscure its meaning. The resolution of this problem cannot be a condition of the development of missional hermeneutics, since it would undoubtedly become an albatross. Yet, it seems counterproductive to proceed with the discussion of missional hermeneutics when so many remain uncertain about the definition of missional in the first place. An understanding of missional theology in terms of two intersecting continuums—missiological–missional and theory–history—suggests a multidimensional understanding of missional and, in turn, signals the need for a full-orbed missional hermeneutic to develop as a revision of the hermeneutical spiral. Therefore, I begin the discussion of missional hermeneutics by plotting various themes and emphases on the landscape of missional theology.

The first distinction necessary for understanding the current discussion is the difference between missional hermeneutics and missiological hermeneutics. While much of the missional church movement is keenly attuned to the logic of mission, it is not especially missiological.1 Missional in its basic adjectival sense refers to anything having to do with mission, which makes the distinction between missional and missiological questionable. But in the context of the hermeneutical discussion, the concerns of missiology as a discipline on one side and the missional church movement on the other are distinguishable, though overlapping. This is somewhat puzzling, considering the fact that the thought of Lesslie Newbigin is ostensibly the primary impetus behind the missional church movement.2 Newbigin was accomplished as both a cross-cultural missionary and a theologian, and his work holds together elements that have become fragmented among his theological heirs. This fragmentation is partly due to the fact that Newbigin’s application of cross-cultural missiological insights to Western culture inspired intracultural reflection that did not sustain the same degree of cross-cultural acuity as Newbigin’s work. Much of what the discipline of missiology has to offer missional hermeneutics arises from its interest in cross-cultural dynamics. This cross-cultural perspective remains relatively marginal in missional church conversations that are particularly attentive to postmodern Western ecclesiological concerns.3

Because these are not by any means mutually exclusive dimensions, I place them on a continuum:

The missiological end of the continuum focuses more on church missions, which until very recently were typically cross-cultural, and concomitantly on anthropology. The missional end of the continuum concentrates on the theology of the missio Dei and, by extension, the local church’s nature as participants in God’s mission. By intersecting these tendencies with a second continuum, which characterizes another typical spectrum of interests in terms of theoria and historia,4 it is possible to plot a number of missional themes (Figure 2). Though current jargon makes it necessary to label one end of the continuum in Figure 1 “missional,” my intention is to advocate the whole collage represented in Figure 2 as an integrative conception of missional theology and, therefore, as indicative of a multidimensional definition of missional.5

The four quadrants this juxtaposition creates allow us to identify key emphases in different corners of the missional theology world, which I label Doctrine, Ministry, Witness, and Worldview. These, in turn, correspond to prominent missional themes: God’s nature (Trinity), God’s kingdom (purpose), God’s story (narrative), and God’s presence (creation). Finally, each emphasis reflects one of Christianity’s four well-known theological norms: tradition, experience, Scripture, and reason. This model intends to illuminate theological tendencies. Ideally, the missional theologian will live right at the theoretical center, where all themes, emphases, and norms inform each other mutually and thoroughly. And in fact, many missional thinkers work from near the center or even move from quadrant to quadrant. Yet, despite the model’s inability to portray the complexities of reality, I hope it will illuminate some real dimensions of missional theology.

Doctrine

Missional and theoretical concerns combine in the trinitarian theology of the missio Dei. Although much of the fruitful work in this area accentuates the biblical depictions of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit instead of the more speculative ontological concerns that have marked trinitarian theology, the missio Dei is nonetheless a deeply trinitarian doctrine and is therefore rooted in the tradition of the church.6

The aphoristic upshot of the emphasis on the missio Dei is that “the mission is God’s,” which the doctrine articulates over against the church’s often historically self-centered mission practices.7 Furthermore, the missio Dei sheds light on the nature and identity of the church as an extension of the missio. “The classical doctrine on the missio Dei as God the Father sending the Son, and God the Father and the Son sending the Spirit was expanded to include yet another ‘movement’: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit sending the church into the world.”8 Therefore, the church is missional by nature.9 Because missional signals a thoroughly trinitarian theology, the missional ecclesiology that emerges is also trinitarian. Newbigin’s The Open Secret establishes the architecture of a missional ecclesiology: “This threefold way of understanding the church’s mission is rooted in the triune nature of God himself. If any one of these is taken in isolation as the clue to the understanding of mission, distortion follows.”10

Working backward through the missio, the first way of understanding the church is in light of pneumatology: “It is thus by an action of the sovereign Spirit of God that the church launched its mission. And it remains the mission of the Spirit. He is central.”11 This is the “church in the power of the Spirit”:

In the movements of the trinitarian history of God’s dealings with the world the church finds and discovers itself, in all the relationships which comprehend its life. It finds itself on the path traced by this history of God’s dealings with the world, and it discovers itself as one element in the movement of the divine sending, gathering together and experience. It is not the church that has a mission of salvation to fulfil to the world; it is the mission of the Son and the Spirit through the Father that includes the church, creating a church as it goes on its way. It is not the church that administers the Spirit as the Spirit of preaching, the Spirit of the sacraments, the Spirit of the ministry or the Spirit of tradition. The Spirit ‘administers’ the church with the events of word and faith, sacrament and grace, offices and traditions. If the church understands itself, with all its tasks and powers, in the Spirit and against the horizon of the Spirit’s history, then it also understands its particularity as one element in the power of the Spirit and has no need to maintain its special power and its special charges with absolute and self-destructive claims. It then has no need to look sideways in suspicion or jealously at the saving efficacies of the Spirit outside the church; instead it can recognize them thankfully as signs that the Spirit is greater than the church and that God’s purpose of salvation reaches beyond the church.

The church participates in Christ’s messianic mission and in the creative mission of the Spirit.12

Participation in Christ’s messianic mission is the essence of the second way of understanding the church in relation to the Trinity. Two areas of controversy are especially prominent among missional theologians in this regard. One is the nature of participation, which is vitally important because the doctrine of the missio Dei developed in the first place during the twentieth-century church’s agony over its history of ecclesiocentrism and colonialism. Newbigin speaks somewhat unreservedly of the “continuance of [Jesus’] mission.”13 The significance of this is twofold: (1) without the church, the mission “will otherwise remain undone,”14 and (2) the distinction between church and kingdom—which is the most important safeguard against ecclesiocentrism in missional thought—remains blurry. For Newbigin, the church is sent “not only to proclaim the kingdom but to bear in its own life the presence of the kingdom.”15 On the other hand, chapter four of the landmark book Missional Church blocks the over-identification of the kingdom with the church by adopting “representation” of the kingdom as its primary model.16 There is not a tremendous difference between these two careful renderings, but they do indicate a polarizing tension in the discussion of “participation,” which remains the fundamental concept in the missional articulation of ecclesiology in relation to Christology.17

The second dispute concerns the relationship between Christology, missiology, and ecclesiology. Michael Frost and Alan Hirsch set the board with the claim that “Christology determines missiology, and missiology determines ecclesiology. It is absolutely vital that the church get the order right.”18 David Fitch takes issue with this ordering because the epistemological function of the church logically gives ecclesiology precedence.19 But in subsequent work, Frost and Hirsch reconfigure the three topoi less linearly.20 Ed Stetzer and David Putman similarly advocate that all three be “in conversation and interaction.”21 Regardless of details, the point is to note that Christology plays a prominent role in missional ecclesiology, both in terms of participation in Jesus’ kingdom mission and in terms of Jesus and his mission being theologically determinative of the church.

The third and final way of understanding the church is in light of the cosmic purposes of the Father—“God who is the creator, upholder, and consummator of all that is.”22 The cosmic scope of this perspective propels two conversations. The first is about the relationship of God to the world. Mark Love, for example, urges a new understanding of the God–church–world relationship in light of social trinitarian understandings of the Father’s relationship to Son and Spirit:

God is social, each person open to the other. But God is also open—open to history, open to creation, open to the stranger. The same kind of dynamic nexus of relationships that characterizes Father, Son, and Spirit applies to creation as well. The world constituted by a triune God is a participatory drama with multiple characters. As Father, Son, and Spirit, God is not only acting on the world, sending to the world, but God is also for the world, with the world, and through the world. God is no longer a series of one-way sendings in a straight line but a participatory God making room for the other with movement in all directions.23

Therefore:

A missional congregation does not merely take God to the world, but participates in the life of the world expecting to find God more deeply. The nature and shape of mission is not already decided but must be discerned in relation to God’s participation in the world. The resources of the gospel are needed for this work of discernment. Clearly, not everything that appears in the world is an appearance of God’s redemptive concern for creation.24

While the christological viewpoint considers the church’s participation in Christ, this conversation focuses especially on the ecclesiological implications of God’s participation in the world.

The second conversation is an extension of the same idea, but here the trinitarian particulars fade into the background. It is about the work of God in the world outside the church, which moves two directions on Figure 2.25 Moving toward the Worldview quadrant are observations about cultures’ reflection of the imago Dei—the innate abilities of human societies to fulfill the cultural mandate through language, reason, and some measure of creative goodness. Within the scope of doctrinal concerns, I label this (Re)Creational Theology.26 Moving toward the Ministry quadrant are observations about some of the purposes of God, which we might label broadly as “human flourishing,” being fulfilled to an extent through social endeavors such as politics, with which the church may have more or less to do in any given situation (that is, the line between Trinitarian Ecclesiology and Political Theology is fuzzy). Once considered a relatively liberal view of the mission of God, there is now wider acceptance among conservative missional thinkers that God’s creating, sustaining, and re-creating relationship to the cosmos implies the advance of his kingdom purposes in the world, to some degree apart from the church. Trinitarian Ecclesiology therefore wrestles with, on one hand, the formation of a community made in the image of Father, Son, and Spirit who exist as a community in relationship with the world and, on the other hand, the creational relationship of God and world that exists prior to and apart from the church.

Ministry

As we move from the theoretical to the historical on the missional end of the spectrum, a shift of theological priority takes place. Here the accent falls on actualizing participation in God’s mission rather than understanding mission in terms of trinitarian theology. In this quadrant, the kingdom is the major theme, and the experience of participating in God’s kingdom purposes becomes the key theological norm. Praxis and participation converge to emphasize the church’s life in the world, which I label Ministry.27

The theological maxim that governs this perspective is that incarnation is the paradigm. Incarnational ministry models itself on the ministry of Jesus—it is the practical outworking of the christological priority discussed above.28 This means service to and sacrifice for the world—that is, one’s neighbors—which may take many forms but maintains a methodological commitment to relationships of solidarity and humility; hence, incarnation assumes cruciformity. The Ministry perspective understands God’s kingdom purposes especially in light of Jesus’ proclamation of good news to the poor (Luke 4:18) in word and deed through his ministry of healing, liberation, and social inclusiveness and his condemnation of institutional evil.

Such an understanding conceives of the inbreaking of the kingdom over against existing social structures, which leads to two varieties of political theology among missional thinkers. One follows the incarnational paradigm into identification with existing structures in order to transform them. Missional practitioners of this approach involve themselves in and confront existing communities and polities redemptively on their own terms from the inside, in light of Jesus’ teachings (risking syncretistic civil religion). The other variety follows the incarnational paradigm into embodiment of alternative structures. Missional practitioners of this approach establish distinct communities and polities that allow Jesus’ teachings both to contrast prophetically with distorted structures and to display the possibility of radically new forms of life (risking escapist sectarianism). As Craig Van Gelder and Dwight Zscheile state, “At stake is how culture and the world are to be viewed: are they to be viewed primarily in positive terms or in negative terms?”29

Either way, the proclamation of the good news of the kingdom is holistic in the Ministry quadrant. This comes to expression in a number of triadic formulas, which are summed up well in Missional Church: community, servant, messenger; kerygma, diakonia, koinonia; words of love, deeds of love, life of love; the truth (message), the life (community), the way (servant); and being witness, doing witness, saying witness.30 To these we should add Bryant Myers’s paradigm in his watershed volume on holistic developmental ministry, Walking with the Poor. Myers’s work with World Vision International in the majority world has a very different context than most of the American missional church conversation, and his cross-cultural developmental work occasions a sophisticated understanding of holism that complements and expands the formulas above. Myers states: “The gospel is not a disembodied message; it is carried and communicated in the life of Christian people. Therefore, a holistic understanding of the gospel begins with life, a life that is then lived out by deed and word and sign.”31

We must also remember that the gospel message is an organic whole. Life, deed, word, and sign must all find expression for us to encounter and comprehend the whole of the good news of Jesus Christ. Life alone is too solitary. Word, deed, and sign alone are all ambiguous. Words alone can be posturing, positioning, even selling. Deeds alone do not declare identity or indicate in whom one has placed his or her faith. Signs can be done by demons and spirits or by the Holy Spirit. It is only when life, deed, word, and sign are expressed in a consistent and coherent whole that the gospel of the Son of God is clear.32

The holism of the Ministry quadrant, whether in Western or majority world contexts, overcomes the spiritual gospel–social gospel dichotomy that plagued the last century. The closing of this gap owes much to the influence of majority world theologians such as Mortimer Arias, René Padilla, Samuel Escobar, and Orlando Costas, who brought liberation theology to bear upon the Western evangelical conception of mission.33 Through the meaning of praxis in liberation theology,34 the Ministry quadrant comes to life as a discrete theological locus—a place from which to talk about God as we come alongside God in solidarity with God’s creation. Distinct from the doctrinal context of tradition, participation in the kingdom of God creates the praxeological context of ministry experience.

Witness

The emphasis I label Witness is where the historical and the missiological intersect. The biblical story of God’s mission through his people here combines with the history of post-apostolic missiones ecclesiae. On the landscape of missional theology, this is where a narrative account of God’s mission stands tall. A variety of ideas converge in the category of Witness: the biblical authors’ witness to God’s mission in history, the particular stories about God’s witnesses (storytellers) in Scripture (i.e., prophets and apostles), the church’s subsequent role as witness (storytellers), and the church’s place in the ongoing story of God’s mission. Again, the intention of delineating quadrants in Figure 2 is not to suggest that “witness” should be limited to a purely verbal function, as though witness cannot be synonymous with “holistic proclamation” or as though the church’s mission practices have been completely detached from “material” concerns. I wish merely to emphasize the notably testimonial nature of the church’s historical mission practices, especially in relation to Scripture, because it bespeaks a distinctive theological emphasis: proclamation, kerygma, rehearsal of the Script itself.

In the exegetical corner of the quadrant, the chief concern is the historical exposition of what mission is in the Bible, in terms of (1) God’s will and work in the world and (2) his people’s participation in his purposes.35 In the church-missions corner of the quadrant the theological interest is twofold: (1) how the church’s missions cohere (historically and presently) with the biblical witness to mission36 and (2) how the church’s missions shape (historically and presently) its own witness to the biblical story.37 The realization that “mission is the mother of theology” is axiomatic for the Witness emphasis.38 Within the Bible this means both that God’s mission is the story’s plot and that biblical authors wrote as participants in God’s mission, forced to theologize from within the crucible of mission. Within the life of the church this means that the church’s own missional engagement must shape her theology. In this quadrant, the accent lies on the cross-cultural nature of witness as the church engages in God’s global mission, and therefore on missionary practices of translation and contextualization. Intracultural incarnational participation on the missional end of the spectrum (Figure 1) often fails to take into account missiological understandings of contextualization despite frequent discussion of culture.

Worldview

In the missiological and theoretical corner of the graph, anthropology and philosophy overlap in their concern about worldview, though the two fields of study have approached the concept in different ways. From a missional theological standpoint, what anthropologists and philosophers find in their studies is predicated on God’s design and presence in creation. Thus, as the trinitarian description of God’s nature is a reflection of God’s story in Scripture, so God’s self-testimony in creation, which is accessible to reason, is a reflection of God’s initiative in the world, which humankind may experience. God’s self-testimony (i.e., general revelation) is accessible to reason because God has made the languages and correlate worldviews that humankind develops to be adequate for that purpose (the effects of sin notwithstanding). His design of humankind and presence in human cultures (Acts 17:24–28) before the arrival of Christian witness is a prevenient grace that makes translatability the theological assumption of the Worldview quadrant.39

Natural Theology—what people might say about God by virtue of his presence in creation and without reference to Christian tradition or Scripture—is a first cousin of (Re)Creational Theology in the Doctrine quadrant. Here philosophy as a Western mode of discourse combines with other cultural varieties of wisdom, and we note that indeed biblical wisdom literature is steeped in creational theology and borrows wisdom from diverse cultures.40 Thus, Natural Theology in Figure 2 designates the products of the capacity of all cultures’ worldviews to perceive and speak about God.

Where (1) missiology’s concerns for translation of the Witness and the development of culturally indigenous theology combine with (2) this innate capacity, the emphasis falls on worldview transformation. The nature of worldviews as intercultural frames of reference, the products of worldviews as naturally theologically generative paradigms, and the transformation of worldviews in terms of conversion, discipleship, and local self-theologizing are the primary concerns of the Worldview quadrant of missional theology.

Dimensions of Missional Theology

If my plotting of missional theology is representative of actual trends and tendencies, then one major implication of the graph is the need for a more integrated view of missional. While there is certainly nothing wrong with a particular missional thinker developing a single dimension (e.g., cross-cultural communication) or working out of a limited frame of reference (e.g., Western ecclesiology), without reference to the bigger picture the result is often an inadvertently reduced portrayal of the meaning of missional. In the service of a full-orbed missional hermeneutic, therefore, I propose the following outline of dimensions of missional theology. For the sake of brevity, I will expand in footnotes only upon the more opaque ideas.

Missional theology should be:

1. Trinitarian (rooted in the missio Dei)

1.1. Narratively ontological41

1.1.1. Keyed to the relational nature of Father, Son, and Spirit as both community and creator

1.1.2. About participation in the sending (missio)

1.2. Narratively teleological42

1.2.1. Keyed to the purposeful plot of the story

1.2.2. About participation in the drama’s continuation

2. Eschatological (attentive to the already–not yet nature of the kingdom)43

2.1. Anticipatory

2.1.1. Keyed to real experience of the Father’s kingdom in Christ through the Spirit—God’s fulfilled purposes (“first fruits”)

2.1.2. About cruciform (humble, self-denying) participation in authentic transformation on personal, communal, and societal levels (experience of the already)

2.2. Teleological

2.2.1. Keyed to the ongoing inbreaking of the Father’s kingdom in Christ through the Spirit—God’s unfulfilled purposes

2.2.2. About cruciform (dependent, hidden) participation in and yearning for the kingdom’s advance (encounter with the not yet)

3. Cultural (attentive to the incarnation as the paradigm of God’s relationship to human particularity)

3.1. Contextualized

3.1.1. Keyed to translation

3.1.2. About participation in the local context

3.2. Intercultural

3.2.1. Keyed to dialogue

3.2.2. About participation in the global context

4. Praxeological (developed in solidarity with those among whom God is at work)

4.1. Experiential

4.1.1. Keyed to mission as the mother of theology

4.1.2. About spiraling reflection on participation

4.2. Holistic44

4.2.1. Keyed to the reconciliation (Col 1:21), consummation (Eph 1:10), and restoration (Acts 3:21) of all things, therefore to all of life (word and deed).

4.2.2. About participation in all dimensions of God’s mission

The State of Play in Missional Hermeneutics

Explicit mention of Scripture is notably missing from my outline of proposed dimensions of missional theology. Despite Scripture’s place on the graph of missional themes and emphases, I do not place it among the dimensions of missional theology because the analysis of the meaning of missional here only serves as prolegomena to the primary task of developing a missional hermeneutic of Scripture. For those who take Scripture, as I do, to be the ultimate theological norm, the articulation of a missional theology must happen under the authority of God exercised through Scripture, but the hermeneutical question is how this happens. In this section I consider trends in missional hermeneutics in relation to the dimensions of missional theology I have outlined above.

Streams in the Gospel and Our Culture Network

George Hunsberger’s recent mapping of missional hermeneutics is presently the primary point of reference.45 He delineates four “streams of emphasis” in the conversation that has developed among Gospel and Our Culture Network interlocutors:

The Missional Direction of the Story

Hunsberger identifies Chris Wright as the primary representative of this approach. The essence of Wright’s missional hermeneutic is the way in which the purposeful story that Scripture narrates as a whole gives meaning to the parts. This is a narrative model of biblical theology in which “God’s mission” is the plot of the story.

The Missional Purpose of the Writings

Darrel Guder is exemplar for this approach, which has to do with “the purpose and aim of the biblical writings, and the canonical authority by virtue of their formative effect.”46 The point is that the purpose of the original authors, identified as equipping God’s people for mission, provides hermeneutical traction by virtue of their function. The emphasis here is not what texts mean per se but how they equip the church for mission.47

The Missional Locatedness of the Readers

Michael Barram stands out as an advocate of this approach. He focuses on the way that the community’s participation in mission shapes the questions the reader brings to the text. Such missional questions allow the text to speak meaningfully to contextual concerns. But asking properly missional questions depends on the community’s missional identity and consciousness.

The Missional Engagement with Cultures

The final stream comes from the work of James Brownson. Hunsberger highlights Brownson’s interest in the hermeneutics present in New Testament authors’ appropriation of the Old Testament. The missional sense of Brownson’s interest in intertextual hermeneutics “springs from a basic observation about the New Testament: The early Christian movement that produced and canonized the New Testament was a movement with a specifically missionary character.”48

While I find this analysis helpful, I think it is possible to parse some of the various sources’ contributions differently. There are two areas that I believe are especially important to spell out more than Hunsberger’s article does. The first regards exegesis. In Michael Barram’s response to Hunsberger, he continues to push a point he has raised for some time: “In the end, I’m still wondering, I guess, how concrete exegetical methodology relates to the notion of a larger, robust hermeneutic.”49 Yet, in his 2007 Interpretation article, Barram has already spelled out the two most vital points for exegesis:

First, the communities to which NT documents were written owed their existence to a missional impulse in early Christianity. God was active in the world, and the fledgling Christian communities found themselves caught up in that activity. Of course, the doctrinal struggles we find would never have arisen apart from a process of early Christian outreach. Second, the NT texts themselves are in some real sense missiological, inasmuch as they equip their original addressees for the community’s vocation in the world.50

This is the exegetical aspect of the assertion that “mission is the mother of theology.” The formulations of Scripture itself (1) were born of participation in the missio Dei and (2) intended to serve the people of God in that context. Therefore, to attempt to understand their original meaning outside of this “rubric,” as Barram calls it, is a methodological error.

I think it is helpful to distinguish point (2) from Guder’s identification of the purpose of the writings. There is a difference between (a) recognizing exegetically an author’s purpose in order to understand his meaning and (b) sharing an author’s purpose in order to reappropriate a passage’s function in new missional settings. There is a strong connection between the two, but it is still important to make the distinction because of “the value of methodological rigor” in biblical studies.51

For the same reason, Barram’s own “located questions” are beyond the scope of historical exegesis, even though it is true that the questions an exegete brings to the text cannot escape locatedness. That is to say, despite the recognition of locatedness, missional hermeneutics should still struggle to understand the author in his location before turning to the present reader in hers. In that sense, I think missional hermeneutics needs to recognize clearly the significance of the two exegetical points Barram makes but also needs to make it clear that in another sense the answer to his lingering question about concrete exegetical methodology is: Exegesis ought to relate to a robust missional hermeneutic as a part of the hermeneutical spiral (see below), not by becoming fundamentally different methodologically.

The second area that needs more clarity is cultural studies. Hunsberger associates Brownson’s interest in the New Testament authors’ multicultural hermeneutics with missiological models developed in recent years.52 Contrary to this comparison, Brownson himself states:

Missional encounters between people are, almost by definition, cross-cultural encounters. To the extent that this is true, then it follows that a missional hermeneutic is one that sees this cross-cultural encounter as the central context out of which interpretation takes place. This is most closely addressed in George’s third category, which focuses on the location of the reader.53

In other words, it is Barram’s “located questions” that come closest to missiological cross-cultural concerns, not the emphases that Hunsberger labels “engagement with cultures.” It is missiology’s struggle with cross-cultural dynamics that constitute its greatest potential contribution to missional hermeneutics. Barram observes:

Perhaps it should not be surprising that sensitivity to social location is evident in recent missiological studies concerned with the character and function of the Bible. Given the historic and geographic scope of missionary activity, practitioners have explored issues of contextualization and pluralistic readerships for years. For that reason, missiological conversations regarding the process of multilateral and intercultural dialogue may be significantly more developed and sophisticated than analogous developments in biblical studies.54

The point is that Hunsberger conflates two very distinct contributions to missional hermeneutics. One deals with exegetically illuminating biblical authors’ missional hermeneutics, whereas the other deals with the similarity between (a) biblical authors’ hermeneutics and (b) the hermeneutical implications of the cultural dynamics that missiologists have been exploring for some time. Therefore, one rich field of study is the missional hermeneutics of the biblical authors themselves. In other words, mission sheds new light on intertextual interpretation. A very different field of study is that of missiology, especially translation and contextualization.

Theses for Exploring a Fuller-Orbed Missional Hermeneutic

In light of the dimensions of missional theology, Hunsberger’s four streams are helpful but also indicate uncharted waters. As a basis for exploring a fuller-orbed missional hermeneutic, I propose the following theses:

1. Missional hermeneutics examines the listening community’s preunderstanding culturally in terms of worldview.55

In his article “Continuing Steps towards a Missional Hermeneutic,” Michael Goheen writes about the gulf between missiology and biblical studies:

Three developments offer signs of hope for a move beyond this impasse that might help to restore a missional hermeneutic: the development of a much broader understanding of mission that has been expressed in terms of the missio Dei; the challenge to higher criticism of new forms of biblical interpretation influenced by, for example, hermeneutical philosophy; and, the entry into the field of scholars who combined a sophisticated understanding of both biblical studies and missiology.56

Goheen represents the trend in missional hermeneutics of utilizing the theoretical construct worldview where these three developments converge.57 The problem of preunderstanding is basic for hermeneutics.58 It deals with the way that the listening community’s constellation of existing knowledge (both cognitive and embodied) and habits of knowledge-making determines the possibility and limits of new understanding—a discussion that takes its cues from postmodern epistemology.59 So much diversity has marked the conceptualization of worldview in philosophy that some doubt its usefulness. Nonetheless, this has been the case in large part because so many thinkers have found the concept to be useful for systematizing the range of concerns present in the idea of preunderstanding. The worldview concept has continued to evolve, and some of the earlier problems with its usage in philosophy are no longer characteristic.60 Like any proposal, worldview has its critics, but for the purposes of the present overview suffice it to say that worldview is still proving fruitful as a theoretical construct that brings together a number of postmodern epistemological concerns in a systematic way.

Since the rise to prominence of the philosophy of language, there has been significant overlap between philosophy and anthropology, and it is precisely in this area of overlap that missiological anthropologists also advocate the worldview concept. Cultural analysis sheds a different light on worldview, but the complementarity of the two disciplines’ usages ultimately produces an even richer model. Because missional hermeneutics attends to epistemic concerns with intercultural sensitivity, this complementarity becomes clear, and worldview emerges as the best model for examining the preunderstanding of particular communities.61

2. Missional hermeneutics attends exegetically to the nature and purposes of God revealed in particular passages. Particularity here is twofold: in relation to the whole of Scripture and in relation to a passage’s immediate context.

In relation to the whole of Scripture, missional hermeneutics pays close attention to “the reality and inevitability of plurality” already evident in the theology of biblical authors.62 This establishes a fundamental orientation for the listening community that forestalls the tendency to build unity upon uniformity and fosters openness to culturally diverse perspectives. Exegetical attention to particularity also prevents a facile synthesis of the whole of Scripture in terms of “mission,” requiring instead a nuanced approach to missional biblical theology that remains open to the dissenting voices of particular passages.

In relation to context, exegesis should naturally be attuned to language, culture, occasion, genre, style, composition, and the like (the study of backgrounds has always been consonant with anthropology). Yet, exegesis should especially take into account that Scripture’s authors wrote in the crucible of participation in God’s mission. Their own formulations are attempts at contextualization, albeit not, of course, in the anthropological mode of current missiology. But the exigencies of mission did compel biblical authors to perceive and draw out new theological implications and articulate them in contextually and situationally appropriate ways.63 This observation yields two distinct hermeneutical contributions.

First, exegesis that attempts to understand an author’s intention without observing the missional context of the writing will fall short in its descriptive endeavor. One facet of missional hermeneutics, thus, is attentiveness to the biblical authors’ participation in the mission of God in order to understand their meaning. Second, doing exegesis in this light renders the authors’ modes of operation as a paradigm for current missional theologizing. Specifically, (1) the authors’ original purpose was to form readers for mission, and (2) the authors make innovative yet cohesive articulations and determinations in imitable ways.64 Insofar as these modes are paradigmatic, exegesis can provide a hermeneutical direction rather than merely extracting prefabricated conclusions or principles. Hermeneutics should therefore be done in service to God’s mission, imitating as far as possible the interpreters par excellence canonized in Scripture.

Finally, a critical aspect of exegesis in missional hermeneutics is the reconstruction of worldviews represented in particular texts. Here especially there is reservation on the part of biblical scholars who have learned to doubt the validity of searching for a biblical author’s “intentions,” which ultimately falls into speculation about an author’s inaccessible psychology. This skepticism finds considerable support in the postmodern hermeneutical conclusion that texts do not give access to the author’s subjectivity. Together these doubts present a significant challenge to the idea that the worldviews of biblical authors can be reconstructed. Yet, we must note that a number of “criticisms” contribute to worldview reconstruction, often piecemeal, whether they intend to or not. This is because, as the anthropological angle makes clear, worldviews are only accessible through cultural analysis—and biblical studies is not shy about historical cultural reconstruction. For example, the New Perspective on Paul is largely a groundswell of exegetical insight based upon a reconstruction of Second Temple Judaism’s worldview. This amounts to understanding justification, for example, not in terms of Paul’s psychology or subjectivity as an author but in terms of his probable frame of reference as a culturally embedded person.

3. Missional hermeneutics perceives the unity of Scripture in terms of the metanarrative of God’s purposes.

Biblical theology finds its continuity (or cohesiveness) in the metanarrative of God’s mission. This is a story about a particular God moving the plot forward toward a particular purpose. Chris Wright, Michael Goheen, and Craig Bartholomew have been leading proponents of this assertion.65 Scripture per se is not a metanarrative; rather, it gives witness to and reveals one. Its range of genres and diversity of perspectives combine into a whole that implies the metanarrative. It is the job of biblical theology to render that metanarrative. Furthermore, the metanarrative engenders the “biblical worldview.” Yet, “the” biblical worldview assumes the pluralism and diversity that exegesis establishes. As a metanarrative of diversity, it addresses, at least to some extent, the concerns of postmoderns who reject totalizing narratives.66 Brownson states it well:

The challenge is to discover the implicit logic and assumptions that both drive and constrain that dynamism and diversity. If we can identify and render explicit that logic and those assumptions, we may be able to articulate a vision for the coherence of the New Testament that invites a variety of creative readings of the New Testament within a dynamic but coherent framework.67

The diversity of Scripture itself is a record of a variety of cultural worldviews in the process of transformation. The unity of Scripture implies a shared metanarrative among the diversity of cultural worldviews. It is not totalizing, but it is transformative, especially in its teleological nature. All cultures are enlisted in God’s mission from their particularity. The canon exists as an expression of this particular unity.

Though N. T. Wright has not (to my knowledge) identified his work as missional hermeneutics, it demonstrates many of the same operating assumptions and has been influential in the field.68 Specifically, his focus on worldview, narrative, and teleological eschatology suggest a missional hermeneutical sensibility.69 One recent book, Scripture and the Authority of God, is especially conscious of God’s mission.70 The book is an outworking of the now well-known hermeneutical proposal that the narrative thrust of Scripture be appropriated interpretively as a drama in which interpreters improvise an act for which the script is not available.71 Cast explicitly in terms of mission, N. T. Wright’s work suggests that one important facet of missional hermeneutics is the juxtaposition of the crucial missional concept of participation in the ongoing mission of God with the narrative hermeneutical logic of participation in the ongoing story of God’s purposes. Cast in terms of worldview, this narrative hermeneutical logic invites further exploration of the way metanarrative generates worldview and, therefore, culture. In this regard, the connection between Wright’s proposal and Kevin Vanhoozer’s The Drama of Doctrine is important, because Vanhoozer develops his hermeneutics in conversation with George Lindbeck’s The Nature of Doctrine—and therefore with key philosophical and anthropological interlocutors whose work informs worldview studies.72 These are connections that have yet to be thoroughly explored, but the result of that endeavor will be, I suspect, a more complete missional hermeneutics.

Finally, due to disciplinary divisions, biblical theology is usually inattentive to trinitarian theology as such. Nonetheless, the metanarrative is missional not only by virtue of its teleology but also in terms of its leading protagonists—Father, Son, and Spirit. Newbigin too found insight in early postliberalism.73 But he believed that narrative must be “the biblical narrative taken as a whole and in the context of a fully Trinitarian doctrine of God.”74 As a missiologist, though, Newbigin was anything but slavish about trinitarian formulations:

It has been said that the question of the Trinity is the one theological question that has been really settled. It would, I think, be nearer to the truth to say that the Nicene formula has been so devoutly hallowed that it is effectively put out of circulation. It has been treated like the talent that was buried for safekeeping rather than risked in the commerce of discussion.75

This is the point at which my earlier proposal of narrative trinitarianism informs missional hermeneutics. In the discursive, cross-cultural encounters of mission, new listening communities hear the story and speak of Father, Son, and Spirit in fresh ways. Yet, the story is still trinitarian. This is vitally important because the community’s life practices may cohere more or less with this particular story, and when they cohere less, the tendencies discussed above mar participation in mission. The incarnational community may embody a christomonistic, utilitarian story; the charismatic community a dualistic, escapist story; and so forth. A narrative trinitarian spirituality, by contrast, forms the basis for interpreting (performing) the story of God’s kingdom in cruciform and Spirit-led glorification of the Father, rather than triumphalism or ecclesiocentrism.

4. Missional hermeneutics brings the biblical worldview into conversation with the listening community’s worldview.

This thesis implies two fundamental iterations of the dialogical worldview encounter. The first iteration entails basic processes. One is the explication of the biblical worldview through the lens of the listening community’s worldview (preunderstanding), though in conversation with other listening communities involved in mission (diachronically through historical theology and synchronically through intercontextual and intercultural dialogue).76 The other is the explication of the listening community’s worldview (Thesis 1). Beyond the telling of the biblical metanarrative over against the community’s reigning metanarrative, beyond the “absorption” of the community into the biblical story and the improvisational theodramatic performance of the biblical script, missional hermeneutics attends analytically77 to the worldviews that the respective metanarratives generate. This requires a functional model of worldview, which is beyond the scope of this paper. At this point, however, the hermeneutical traction of missiological contextualization studies becomes evident. Nonetheless, there remains significant work to do in the further development of functional worldview models as well as the practical application of such insights in real communities. These tasks must be undertaken, because in order to ask hermeneutically useful located questions it is not enough that the listening community be located; it must discern its location.

The second iteration of the process happens in the listening community’s missional encounters in the world. Here missiological models of communication become relevant, though I am recasting the process in terms of worldview encounter rather than merely translation-communication. Translatability—the commensurability of worldviews—is the operative assumption,78 and linguistic philosophy provides a great deal of insight into worldview encounters, but the operative metaphor is dialogue. The dialogical encounter assumes mutuality, and therefore the goal of transforming worldviews according to the biblical worldview is not unilateral. Rather, the encountered community’s worldview becomes another lens that both provides perspective and requires transformation, and the original listening community finds new interpretive insight in the encounter through identification, empathy, and solidarity. In this sense, the incarnational impulse of Christianity rejects an imperialistic understanding of transforming worldviews and instead seeks to understand transformation mutually as living in dialogue and tension with the distinctiveness of each cultural worldview, while affirming the normativeness of the biblical metanarrative.79

5. Missional hermeneutics assumes that the listening community’s participation in God’s mission is epistemologically relevant.

The hermeneutical fruit of worldview transformation according to the biblical metanarrative is the development of missional forms of life. Forms of life, then, are both what we do in coherence with our worldview (determinations, applications, actualizations) and what we do in correspondence to the reality that our worldview presumes beyond itself. Participation in reality inevitably reforms a worldview. If the mission of God is “the true story, the true myth, the true history of the whole world,”80 it is not just “public truth”81 to be told but also truth in which the community can participate as it listens. This is the epistemology of praxis that missional hermeneutics learns primarily from liberation theology but expands to a wider vision of God’s mission than just solidarity with the poor. In short, forms of life specifically coherent with God’s purposes beyond the listening community reshape the community’s worldview and thereby focus its hermeneutical lens.

To say that missional questions are epistemologically privileged is not to say that they are determinative, nor is it to say that all missional experience coheres equally with the biblical metanarrative. Rather, it is to say that missional hermeneutics affirms that intentional engagement in mission can shed light on the meaning of the Bible’s story of mission. Stated more simply, missional hermeneutics assumes that because the story of the Bible is ongoing, the interpreter is able to participate in it and therefore understand it more completely from the inside rather than merely analyze it from the outside. But because the biblical story is the story of the missio Dei, only participation in the missio Dei as such affords that hermeneutical advantage.

For similar reasons, spiritual disciplines are vitally important to missional hermeneutics, not because they are a tool for accessing transcendental insight or short-circuiting the rest of the hermeneutical process through revelatory ecstasy, but because they are the historical church’s concrete practices of abiding in the Spirit of God—of living in the reality that the biblical metanarrative asserts. Narrative trinitarian spirituality assumes that the missio Dei is currently about God’s Spirit working before, in, and through the church in the world. Thus, if the question is not simply “What would Jesus do?” but “What is the Spirit doing?” then the church needs to reappropriate spiritual disciplines for mission and, specifically, for discernment through missional hermeneutics.82

Finally, ministry is not an end in itself, and the community is not a producer of goods and services—either for itself or “the other.” Service is a lifestyle of communion with God in the world, upon which the listening community reflects. One area of reflection is the experience of God’s redemptive presence (the actualization of human flourishing). Another area of reflection is the experience of God’s creational presence (the insights of cultural difference, in conjunction with Thesis 4). Therefore, the facilitation of practical involvement in mission is a hermeneutical commitment. This leads to practical questions about equipping and mobilizing community members as well as mediating subsequent community dialogue and discernment. Participation also spirals back to Guder’s question regarding passages’ functions in equipping the people of God for mission, providing another hermeneutical handhold.

Conclusion: Revisioning the Hermeneutical Spiral Missionally

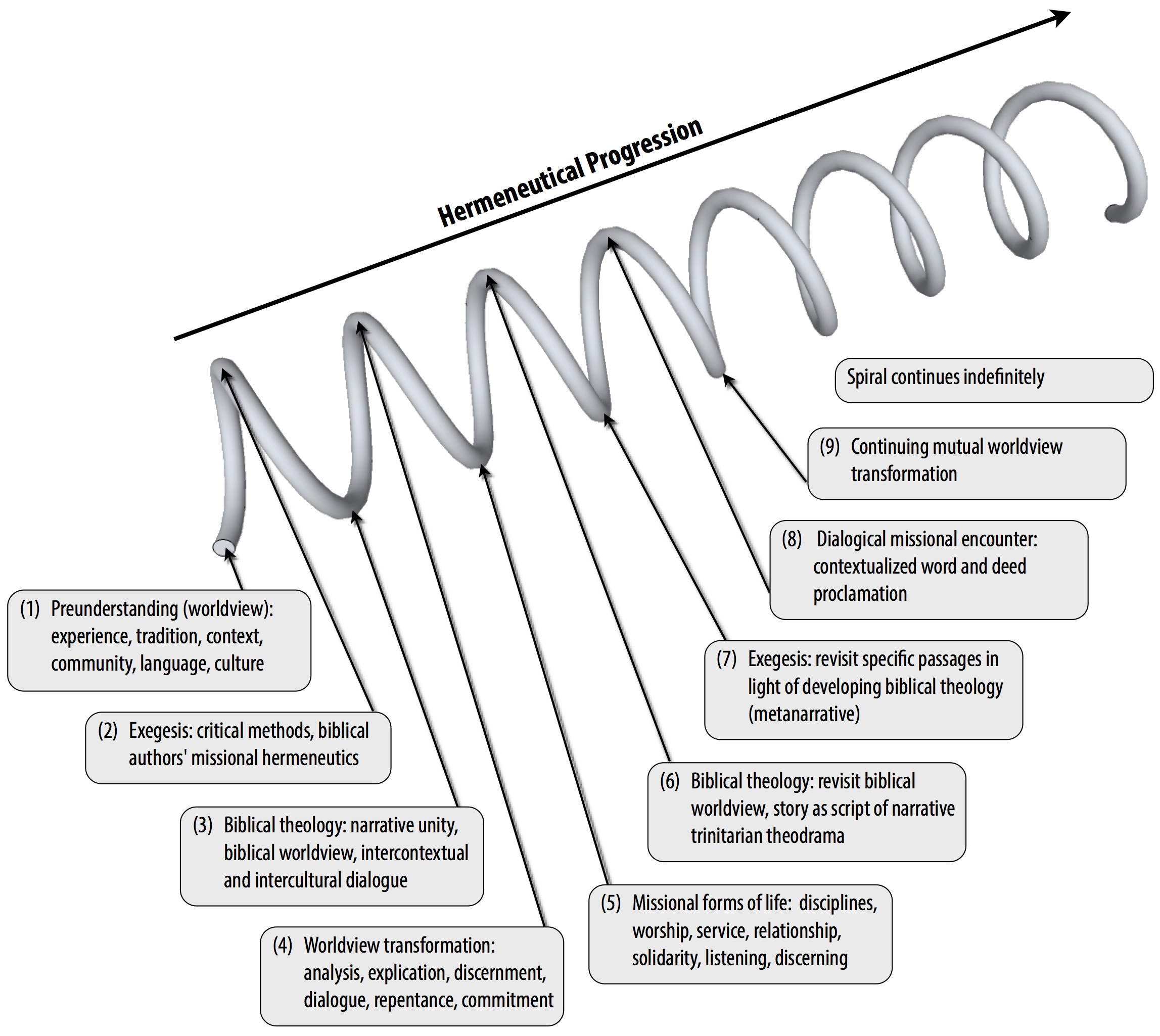

The spiral has proven to be a helpful model for portraying the relationship between established aspects of the hermeneutical circulation. Specific versions of the model are not without their problems. For example, Grant Osborne’s The Hermeneutical Spiral, which presents probably the most influential version, utilizes Noam Chomsky’s transformational grammar in a way that reduces hermeneutics to the extraction and restatement of underlying universal propositions.83 The spiral model itself remains insightful, though, and the missional theses I have proposed here serve as a course correction for some of the major issues with Osborne’s use of transformational grammar, especially in his definition of contextualization.84 As the missional identity and consciousness of the listening community emerges through the transformation of its worldview, the hermeneutical progression assumes a missional direction. This looks something like Figure 3:

For simplicity, I enumerate a sequence of steps, though in the life of a community the hermeneutical spiral is never neat and sequential. It should, however, be progressive, cyclical, and take every part of the circulation to be theologically generative. Ultimately, missional hermeneutics is not sui generis. The missional church must place herself under the authority of God in Scripture, and many of the hermeneutical tools already at her disposal are indispensable to that calling. But the mission of God—the telos—is what determines the progression’s trajectory and, consequently, the hermeneutical means to that missional end. Therefore, I suggest that the hermeneutical spiral revisioned as essentially and thoroughly missional is a model worthy of further exploration.

Greg McKinzie (http://gregandmeg.net/greg) is a missionary in Arequipa, Peru, where he partners in holistic evangelism with Team Arequipa (http://teamarequipa.net) and The Christian Urban Development Association (http://cudaperu.org). He is a graduate (MDiv) of Harding School of Theology and the managing editor of Missio Dei.

Bibliography

Allen, Roland. Missionary Methods: St. Paul’s or Ours? American ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1962 [1912].

Arias, Mortimer. Announcing the Reign of God: Evangelization and the Subversive Memory of Jesus. Lima, OH: Academic Renewal Press, 1984.

Ayers, Adam D. “In Search of the Contours of a Missiological Hermeneutic.” Unpublished dissertation (Fuller Theological Seminary, May 2011).

Barram, Michael. “The Bible, Missions, and Social Location: Toward a Missional Hermeneutic.” Interpretation 61, no. 1 (January 2007): 42–58.

________. “ ‘Located’ Questions for a Missional Hermeneutic.” The Gospel and Our Culture Network. Nov. 1, 2006. http://www.gocn.org/resources/articles/located-questions-missional-hermeneutic.

________. “A Response at AAR to Hunsberger’s ‘Proposals…’ Essay.” The Gospel and Our Culture Network. Jan. 28, 2009. http://www.gocn.org/resources/articles/response-aar-hunsberger-s-proposals-essay.

Bartholomew, Craig G., and Michael W. Goheen. The Drama of Scripture: Finding Our Place in the Biblical Story. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004.

Bauckham, Richard. Bible and Mission: Christian Witness in a Postmodern World. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003.

Bevans, Stephen B. Models of Contextual Theology. Rev. and exp. ed. Faith and Cultures. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2002.

Bosch, David J. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. American Society of Missiology Series 16. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1991.

Brownson, James V. “A Response at SBL to Hunsberger’s ‘Proposals…’ Essay.” The Gospel and Our Culture Network. Jan. 28, 2009. http://www.gocn.org/resources/articles/response-sbl-hunsbergers-proposals-essay.

________. Speaking the Truth in Love: New Testament Resources for a Missional Hermeneutic. Christian Mission and Modern Culture. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1998.

Chung, Paul S. Reclaiming Mission as Constructive Theology: Missional Church and World Christianity. Kindle ed. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2012.

Costas, Orlando E. Liberating News: A Theology of Contextual Evangelization. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1989.

Decree Ad Gentes on the Mission Activity of the Church 2. http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decree_19651207_ad-gentes_en.html.

Escobar, Samuel. The New Global Mission: The Gospel from Everywhere to Everyone. Christian Doctrine in Global Perspective. Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2003.

Fitch, David. “Missiology Precedes Ecclesiology: The Epistemological Problem.” Reclaiming the Mission. http://www.reclaimingthemission.com/?p=187.

Flemming, Dean. Contextualization in the New Testament: Patterns for Theology and Mission. Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2005.

Fretheim, Terence E. God and World in the Old Testament: A Relational Theology of Creation. Nashville: Abingdon, 2005.

Frost, Michael, and Alan Hirsch. ReJesus: A Wild Messiah for a Missional Church. Kindle ed. Grand Rapids: BakerBooks, 2009.

________. The Shaping of Things to Come. Innovation and Mission for the 21st-Century Church. Rev. and updated Kindle ed. Grand Rapids: BakerBooks, 2013.

Goheen, Michael W. “Bible and Mission: Missiology and Biblical Scholarship in Dialogue.” In Christian Mission: Old Testament Foundations and New Testament Developments, ed. Stanley E. Porter and Cynthia Long Westfall, 208–35. McMaster New Testament Studies Series. Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2010.

________. “Continuing Steps towards a Missional Hermeneutic.” Fideles: A Journal of Redeemer Pacific College 3 (2008): 49–99.

________. A Light to the Nations: The Missional Church and the Biblical Story. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011.

________. “The Mission of God’s People and Biblical Interpretation: Exploring N. T. Wright’s Missional Hermeneutic.” A Dialogue with N. T. Wright. Scripture and Hermeneutics Seminar Meeting. San Francisco. November 18, 2011.

Goheen, Michael W. and Craig G. Bartholomew. Living at the Crossroads: An Introduction to Christian Worldview (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

Gorman, Michael J. Inhabiting the Cruciform God: Kenosis, Justification, and Theosis in Paul’s Narrative Soteriology. Kindle ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009.

________. “Participation and Mission in Paul.” Cross Talk ~ Crux Probat Omnia. http://www.michaeljgorman.net/2011/12/12/participation-and-mission-in-paul.

Guder, Darrell L., ed. Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America. Gospel and Our Culture Series. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998.

Guder, Darrell L. “Missional Hermeneutics: The Missional Authority of Scripture—Interpreting Scripture as Missional Formation.” Mission Focus: Annual Review 15 (2007): 106–21.

Hesselgrave, David J. “Syncretism: Mission and Missionary Induced?” In Contextualization and Syncretism: Navigating Cultural Currents, ed. Gailyn Van Rheenen, 71–98. Evangelical Missiological Society Series 13. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2006.

Hiebert, Paul G. Missiological Implications of Epistemological Shifts: Affirming Truth in a Modern/Postmodern World. Christian Mission and Modern Culture. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1999.

________. Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

Hunsberger, George R. “Proposals for a Missional Hermeneutic: Mapping a Conversation.” Missiology: An International Review 39, no. 3 (July 2011): 309–21.

Hunsberger, George R., and Craig Van Gelder, eds. The Church between Gospel and Culture: The Emerging Mission in North America. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996.

Kähler, Martin. Schriften zur Christologie und Mission: Gesamtausgabe der Schriften zur Mission. Theologische Bücherei 42. Munich: Chr. Kaiser Verlag, 1971.

Kirk, J. Andrew. “How a Missiologist Utilizes the Bible.” In Bible and Mission: A Conversation between Biblical Studies and Missiology, ed. Rollin G. Grams, et al., 246–68. Schwarzenfeld, Germany: Neufeld Verlag, 2008.

Kirk, J. Andrew, and Kevin J. Vanhoozer, eds. To Stake a Claim: Mission and the Western Crisis of Knowledge. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1999.

Klink, Edward W., and Darian R. Lockett. Understanding Biblical Theology: A Comparison of Theory and Practice. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012.

Kraft, Charles H. Worldview for Christian Witness. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2008.

Love, Mark. “Missio Dei, Trinitarian Theology, and the Quest for a Post-Colonial Missiology.” Missio Dei: A Journal of Missional Theology and Praxis 1 (August 2010): 37–49.

McKinzie, Greg. “An Abbreviated Introduction to the Concept of Missio Dei.” Missio Dei: A Journal of Missional Theology and Praxis 1 (August 2010): 9–20.

Moltmann, Jürgen. The Church in the Power of the Spirit: A Contribution to Messianic Ecclesiology. Translated by Margaret Kohl. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993.

Moreau, A. Scott. Contextualization in World Missions: Mapping and Assessing Evangelical Models. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2012.

Myers, Bryant L. Walking with the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development. Rev. and exp. Kindle ed. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2011.

Naugle, David K. Worldview: The History of a Concept. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002.

Newbigin, Lesslie. Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture. Kindle ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1986.

________. The Gospel in a Pluralist Society. Kindle ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989.

________. The Open Secret: An Introduction to the Theology of Mission. Rev. ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995.

Osborne, Grant R. The Hermeneutical Spiral: A Comprehensive Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. Rev. and exp. Kindle ed. Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2006.

Padilla, C. René. “Holistic Mission.” In Evangelical Advocacy: A Response to Global Poverty. “Holistic Mission” (2012), 12–24. Papers, PDF Files, and Presentations. Book 9. http://place.asburyseminary.edu/theologyofpovertypapers/9.

________. Mission between the Times. Rev. and exp. ed. Carlisle, England: Langham Monographs, 2013.

Plummer, Robert L., and John Mark Terry, eds. Paul’s Missionary Methods: In His Time and Ours. Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2012.

Powell, Mark. Centered in God: The Trinity and Christian Spirituality. Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 2014 [forthcoming].

Redford, Shawn B. Missiological Hermeneutics: Biblical Interpretation for the Global Church. American Society of Missiology Monograph Series 11. Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2012.

Sanneh, Lamin. Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture. American Society of Missiology Series 13. Rev. and exp. ed. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2009.

Schnabel, Eckhard J. Paul the Missionary: Realities, Strategies, and Methods. Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2008.

Schreiter, Robert J. Constructing Local Theologies. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1985.

Sire, James W. Naming the Elephant: Worldview as a Concept. Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2004.

Stetzer, Ed, and David Putman. Breaking the Missional Code: Your Church Can Become a Missionary in Your Community. Kindle ed. Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 2006.

Thiselton, Anthony C. Hermeneutics: An Introduction. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009.

Van Gelder, Craig, and Dwight J. Zscheile. The Missional Church in Perspective: Mapping Trends and Shaping the Conversation. The Missional Network. Kindle ed. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011.

Van Rheenen, Gailyn. “Syncretism and Contextualization: The Church on a Journey Defining Itself.” In Contextualization and Syncretism: Navigating Cultural Currents, ed. Gailyn Van Rheenen, 1–29. Evangelical Missiological Society Series 13. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2006.

Vanhoozer, Kevin J. The Drama of Doctrine: A Canonical-Linguistic Approach to Christian Doctrine. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2005.

Walls, Andrew F. The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1996.

Willard, Dallas. The Spirit of the Disciplines: Understanding How God Changes Lives. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

Wright, Christopher J. H. The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2006.

Wright, N. T. “Imagining the Kingdom: Mission and Theology in Early Christianity.” Inaugural Lecture. University of St. Andrews. St. Mary’s College (Faculty of Divinity). October 26, 2011. http://ntwrightpage.com/Wright_StAndrews_Inaugural.htm.

________. The New Testament and the People of God. Vol. 1 of Christian Origins and the Question of God. London: SPCK, 1992.

________. Scripture and the Authority of God: How to Read the Bible Today. New York: HarperOne, 2005.

1 This is meant to be a generalization about tendencies. Notable exceptions can be found, for example, in chapters of George R. Hunsberger and Craig Van Gelder, eds., The Church between Gospel and Culture: The Emerging Mission in North America (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996).

2 Craig Van Gelder and Dwight J. Zscheile, The Missional Church in Perspective: Mapping Trends and Shaping the Conversation, The Missional Network, Kindle ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011), 36–39.

3 Ibid., 168–69.

4 I do not intend this terminology to evoke the technical usages developed among the Church Fathers; theoria and historia here respectively denote “reflection” or “contemplation” and “event” or “actualization” in a basic sense, without promoting a “spectator” epistemology on the theoretical end or an empiricist epistemology on the historical end.

5 Adam D. Ayers, “In Search of the Contours of a Missiological Hermeneutic,” unpublished dissertation (Fuller Theological Seminary, May 2011), 18–19, perceptively distinguishes between “mission hermeneutics” (those done in mission), “missional hermeneutics” (those done conscious of God’s and the church’s “mission orientation”), and “missiological hermeneutics” (those done self-analytically through critical disciplines). Since my hope is that missional hermeneutics will become increasingly more missiological, I will use the term missional for the hermeneutics that intends to synthesize all three perspectives’ insights.

6 This sentence serves to highlight my caveat about the descriptive nature of Figure 2. The Doctrine emphasis in missional theology is not necessarily configured in contradistinction from the scriptural concerns of the Witness emphasis; the distinction is purely a description of where current interlocutors place their theological accents. Likewise, placing the theme God’s Kingdom in relation to the theological norm of experience does not serve to make a hard separation from the norm of Scripture. Kingdom is obviously a biblical category. Still, many who emphasize the kingdom in missional theology do so in terms of participation in God’s kingdom as it unfolds in the world beyond and before the church. The theological emphasis of the kingdom theme falls on the experience of participation in God’s kingdom purposes. This is not unbiblical—far from it—but it does reveal a different location on the continuum of theological emphases than that of the narrative theme.

7 Greg McKinzie, “An Abbreviated Introduction to the Concept of Missio Dei,” Missio Dei: A Journal of Missional Theology and Praxis 1 (August 2010): 9–20.

8 David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission, American Society of Missiology Series 16 (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1991), 390.

9 See variously: Decree Ad Gentes on the Mission Activity of the Church 2, http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decree_19651207_ad-gentes_en.html; Lesslie Newbigin, The Open Secret: An Introduction to the Theology of Mission, rev. ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995) 1; Bosch, 9, 390, 519.

10 Newbigin, Open Secret, 65. Van Gelder and Zscheile, 53–4, note that one issue in the seminal work Missional Church remains unresolved in much of the missional church literature:

One is left with a missional church that has two underintegrated views of the work of God in the world in relation to the missio Dei and the reign of God. One view posits a missional church shaped primarily by the message of Jesus and responsible for embodying and emulating the life that Jesus lived. The other view proposes a missional church shaped primarily by the power and presence of the Spirit, who creates, gifts, empowers, and leads the church into engaging in a series of ecclesial practices. Clearly all these authors understood these views to be complementary. But the argument in the book did not adequately integrate the sending work of God in relation to the work of the Son and the work of the Spirit.

The critique offered here does not argue that the authors did not have an understanding of the person and work of Christ or the person and work of the Spirit; evidence is clear that they did. Rather, the point being made is that utilizing primarily a Western view of the Trinity can lead to a functional modalism where the works of the three persons of God become separated from one another.

The point is well made. I suggest, in fact, that many of the themes and emphases I will plot here remain unintegrated or unappreciated, depending on the interlocutor, and should be brought together comprehensively. Taken as a whole, though, missional thinkers are an identifiable group, and between them the “underintegrated” ideas are present—including social trinitarian ideas that balance the Western view. Nonetheless, the authors make a helpful observation that I hope a return to Newbigin’s theological framework can help address.

11 Newbigin, Open Secret, 58.

12 Jürgen Moltmann, The Church in the Power of the Spirit: A Contribution to Messianic Ecclesiology, trans. Margaret Kohl (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993), 64–65; see also 10–11.

13 Newbigin, Open Secret, 47.

14 Ibid., 48.

15 Ibid., 49.

16 Darrell L. Guder, ed., Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America, Gospel and Our Culture Series (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), ch. 4. See Van Gelder and Zscheile, 56–59, for a nuanced account of the diverse views of the kingdom present in Missional Church, which is also relevant to the Ministry quadrant discussed below.

17 In a personal communication, Mark Powell suggested that it is better to speak of “participating in the ongoing ministry of Jesus” instead of “continuing Jesus’ ministry.” For a fuller statement, see Mark Powell, Centered in God: The Trinity and Christian Spirituality (Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 2014 [forthcoming]). This distinction, which emphasizes the present activity of the resurrected Lord, is consonant with Newbigin’s comments on the present sovereignty of the Spirit in mission. Additionally, for Newbigin “continuance” is chastened in terms of cruciformity and therefore hiddenness (Newbigin, Open Secret, 52–55). See also Michael Gorman’s work on the connection between cruciformity, participation in Christ, and mission: Michael J. Gorman, “Participation and Mission in Paul,” Cross Talk ~ Crux Probat Omnia, http://www.michaeljgorman.net/2011/12/12/participation-and-mission-in-paul vis-à-vis Michael J. Gorman, Inhabiting the Cruciform God: Kenosis, Justification, and Theosis in Paul’s Narrative Soteriology, Kindle ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009).

18 Michael Frost and Alan Hirsch, The Shaping of Things to Come: Innovation and Mission for the 21st-Century Church, rev. and updated Kindle ed. (Grand Rapids: BakerBooks, 2013), Kindle locs. 463–64.

19 David Fitch, “Missiology Precedes Ecclesiology: The Epistemological Problem,” Reclaiming the Mission, http://www.reclaimingthemission.com/?p=187.

20 Michael Frost and Alan Hirsch, ReJesus: A Wild Messiah for a Missional Church, Kindle ed. (Grand Rapids: BakerBooks, 2009), Kindle loc. 903.

21 Ed Stetzer and David Putman, Breaking the Missional Code: Your Church Can Become a Missionary in Your Community, Kindle ed. (Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 2006), Kindle locs. 853–97.

22 Newbigin, Open Secret, 30.

23 Mark Love, “Missio Dei, Trinitarian Theology, and the Quest for a Post-Colonial Missiology,” Missio Dei: A Journal of Missional Theology and Praxis 1 (August 2010): 44–45; cf. Van Gelder and Zscheile, 111–14.

24 Love, 46; emphasis added.

25 This is somewhat different than, but related to, Van Gelder and Zscheile’s “generalized secular views of missio Dei and the reign of God,” which they make in distinction from “specialized views” and their preferred “integrated view,” 56–59. In the (Re)Creational direction, a missional interlocutor may focus more or less on the role of God through the Holy Spirit or the role of the church.

26 See Terence E. Fretheim, God and World in the Old Testament: A Relational Theology of Creation (Nashville: Abingdon, 2005), for an incisive biblical account of the relational dynamics between God and creation that pertain to a particularly missional creational theology. See especially pp. 10–13 for a correction to the overpowering redemptive concerns that mark much of the traditional doctrine of creation, thereby distorting a biblical vision of original creation, ongoing creation, and renewed creation.

27 In this usage of “ministry,” I have in mind diakonia according to Jesus’ understanding of his humble, sacrificial relationship to the world (Mark 10:35–45), which carries significant political implications regarding the church’s way of life in the world. For a similar use of diakonia, see Paul S. Chung, Reclaiming Mission as Constructive Theology: Missional Church and World Christianity, Kindle ed. (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2012), Kindle locs. 3536–44.

28 For a positive assessment, see Van Gelder and Zscheile, 114–15; but see pp. 106–7 for an important critique of christomonism “under the guise of an incarnational approach” and the instrumentalism that incarnational missional approaches often evince.

29 Van Gelder and Zscheile, 60. I agree that this is a major, perhaps the major, discrepancy among missional church thinkers. Very similarly to the point I make above, they state:

Newbigin had focused on the church’s role in the engagement of “gospel and culture,” a focus that was also the initial conversation for the first decade of the GOCN. An important implication of this perspective shift [away from culture] in Missional Church is that much of the missional literature today fails to adequately engage the complex interaction between the gospel and our culture(s). It tends to follow the logic of the approach of a sending God. This logic conceives of the world as something “out there” into which the church is being sent. The church’s embeddedness in culture is left unexplored, and the reciprocal interactions between church and culture are left unexamined. (61)

This is essentially the point of the distinction I draw between missional and missiological.

30 Guder, Missional Church, 102.

31 Bryant L. Myers, Walking with the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development, Rev. and exp. Kindle ed. (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2011) Kindle locs. 6316–18.

32 Ibid., Kindle locs. 6330–34.

33 Mortimer Arias, Announcing the Reign of God: Evangelization and the Subversive Memory of Jesus (Lima, OH: Academic Renewal Press, 1984); C. René Padilla, Mission between the Times, rev. and exp. ed. (Carlisle, England: Langham Monographs, 2013); Orlando E. Costas, Liberating News: A Theology of Contextual Evangelization (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1989); Samuel Escobar, The New Global Mission: The Gospel from Everywhere to Everyone, Christian Doctrine in Global Perspective (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2003), ch. 9.

34 Anthony C. Thiselton, Hermeneutics: An Introduction (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 261, states the technical definition clearly and succinctly:

“Praxis,” Berryman urges, is not merely “practice” in opposition to theory, but theory and practical conduct based on theory. The term is often misused to mean merely “practice” in Christian circles, and its philosophical and technical origins in Aristotle, Hegel, Feuerbach, Marx, and Sartre are often forgotten. Richard Bernstein helps us to put the record straight. Marx uses the term when he observes in his eleventh thesis on Feuerbach: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it” (italics in original). In practice this involves a going out of oneself and a commitment to God and our neighbor.

35 The exemplar here is undoubtedly the bulk of Christopher J. H. Wright, The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2006).

36 Roland Allen, Missionary Methods: St. Paul’s or Ours?, American ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1962 [1912]), establishes this field of study. Recent works in the tradition of Allen’s work include Eckhard J. Schnabel, Paul the Missionary: Realities, Strategies, and Methods (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2008) and Robert L. Plummer and John Mark Terry, eds., Paul’s Missionary Methods: In His Time and Ours (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2012).

37 In other words, how the missionary contextualizes the message. A. Scott Moreau, Contextualization in World Missions: Mapping and Assessing Evangelical Models (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2012), presents a thorough picture of the field at present.

38 Martin Kähler, Schriften zur Christologie und Mission: Gesamtausgabe der Schriften zur Mission, Theologische Bücherei 42 (Munich: Chr. Kaiser Verlag, 1971), 190, quoted in Bosch, 16.

39 Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture, American Society of Missiology Series 13, rev. and exp. ed. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2009), chs. 1–2; see also Andrew F. Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1996), ch. 3.

40 Chris Wright, 441:

We turn now to a section of the biblical canon that is often neglected in books about the biblical foundations for mission (as it often has been in books on biblical theology in general also): the Wisdom Literature. For here we find within the Scriptures of ancient Israel a broad tradition of faith and ethics built on a worldview that employs the wide-angle lens of precisely this whole-creation and whole-humanity perspective.