Is renewal possible? Is there hope? Are there ready ears to hear the message of God’s prophets? What patterns of renewal are being proposed? Anthony Wallace’s classic theory of revitalization movements provides a framework for examining the potential renewal of Churches of Christ. In the contemporary context of cultural disintegration, three paradigms of renewal compete. Among them, faithful presence and gracious hospitality is the counter-cultural model of missional renewal that reflects the life of Jesus.

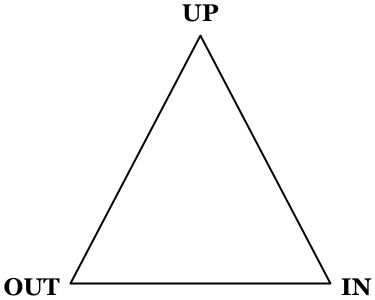

The simplest definition of a missional church is an UP – IN – OUT diagram that illustrates the life of Jesus. He lived UP—in relationship with his Father; he lived IN—in relationship with his chosen followers; and he lived OUT—in relationship with the hurting world around him. Jesus modeled this three-dimensional living when he prayed all night before selecting his twelve apostles (UP), brought them into community (IN), and then went out to minister with them (OUT) (Luke 6:12–19). Likewise, God desires that his people live in these relationships.1 The paradox is that living the rhythm of UP, IN, and OUT is not easy, especially in the United States, a nation characterized by fragmentation and individualism.

The simplest definition of a missional church is an UP – IN – OUT diagram that illustrates the life of Jesus. He lived UP—in relationship with his Father; he lived IN—in relationship with his chosen followers; and he lived OUT—in relationship with the hurting world around him. Jesus modeled this three-dimensional living when he prayed all night before selecting his twelve apostles (UP), brought them into community (IN), and then went out to minister with them (OUT) (Luke 6:12–19). Likewise, God desires that his people live in these relationships.1 The paradox is that living the rhythm of UP, IN, and OUT is not easy, especially in the United States, a nation characterized by fragmentation and individualism.

The Cultural Context of Euro-American Missions

Understanding this rhythm of life is immensely important in the United States of America, because social fragmentation and contemporary management models have displaced this spiritually formative mode of living as God’s chosen people.

Fragmentation

Bowling Alone describes North America’s loss of “social capital” beginning around 1960. The book, whose subtitle is The Collapse and Revival of American Community, warns that unless Americans find ways to reconnect with one another, they will experience a deepening impoverishment in their lives and communities.2 In Great Good Place, Ray Oldenburg observes that in suburban USA “a man works in one place, sleeps in another, shops somewhere else, finds pleasure and companionship where he can, and cares about none of these places.”3 Christians within our churches are also experiencing this fragmentation of social capital! Their communities of faith frequently have little connection to their neighborhoods, their work places, and the schools where their children learn.

Management

The American church also suffers from a crisis of leadership. “Our culture, and as part of it the church, has developed into a management-oriented society. We want to manage growth, manage productivity, and manage human resources.”4 Our leaders have inadvertently become organizers of ministry rather than makers of disciples in the context of imitative ministry. Dan Kimball suggests changing our focus on leadership: “Leadership in the emerging church is no longer about focusing on strategies, core values, and mission statements, or church-growth principles. It is about leaders first becoming disciples of Jesus with prayerful, missional hearts that are broken for the emerging culture. All the rest will follow from this, not the other way around.”5 Breen and Cockram prophetically say: “We need leaders who will step out of ‘managing church’ and make discipling others their primary objective. The time has come to humbly acknowledge before God that we have failed to train men and women to lead in the style of Jesus. Whether through ignorance or fear, we have taken the safe option, training pastors to be theologically sound and effective managers of institutions rather than equipping them with the tools they need to disciple others.”6

Our leaders have become organizers of ministry rather than makers of disciples.

I am often in meetings with leaders who have planted or are leading large churches but prayerfully confess that their churches are not sustainable in this fragmented American cultural climate and that many of their members have not developed the rhythms of living as disciples of Jesus.

Reflection on Disintegration and Revitalization

Anthony Wallace’s classic essay on “revitalization movements” helps us evaluate what has been occurring in different streams of Churches of Christ. Revitalization movements are “deliberate, conscious, organized efforts by members of a society to create a more satisfying culture.”7 A society’s leaders deliberately and consciously seek some type of revitalization as tension increases when older paradigms no longer seem tenable. A more plausible, even more satisfying, culture is created out of this organized effort to revitalize a disintegrating culture. These revitalization movements occur during times of widespread stress and disillusionment with existing cultural beliefs.

Despite cultural variations, Wallace perceives that movements follow a remarkably uniform pattern of disintegration and renewal throughout the world.8 He outlines five stages of a revitalization cycle: (1) the steady stage, (2) the period of increased individual stress, (3) the period of cultural distortion, (4) the period of revitalization, and (5) the new steady stage. Some movements fragment and disintegrate during times of cultural distortion because appropriate revitalization does not occur. In this paper I apply Wallace’s stages to different streams of Churches of Christ, explaining what has occurred and is occurring during each stage, and then describe three contemporary models of revitalization.

Some movements disintegrate in times of cultural distortion because revitalization does not occur.

The Steady Stage

I distinctly remember the steady stage as a child living in Iowa. My parents left our Dutch Reform heritage in south-central Iowa and became members of the Churches of Christ. They felt that the Church of Christ was the original church founded on the Day of Pentecost soon after the resurrection of Jesus. Churches of Christ, they believed, followed the Bible while the denominations followed human creeds and customs. They “came to Christ” by following the “five steps of salvation”: hearing the Word of God, believing what it says, repenting of their sins, confessing that Jesus was Savior, and being baptized for remission of sins. They believed they were part of the one true church and fervently evangelized out of this assumption. They studied the Bible topically through a hermeneutic of “command, example, or necessary inference.” I grew up within this environment and, as an undergraduate, led campaigns for Christ from Harding University that reflected these ideologies. I believed what F. W. Mattox once wrote: “The church of Jesus Christ is neither Jewish, Catholic, nor Protestant. It is non-denominational in its origin, worship and organization. It is the body of Christ, functioning according to the New Testament directions, organized according to New Testament patterns and worshipping according to New Testament instructions, extensive enough to embrace in its fellowship all who comply with God’s requirements and who thus become a part of that body.”9

The Period of Increased Individual Stress

Tension rises during the period of increased individual stress. Members have difficulty coping with their traditional perceptions of reality in the midst of changing times. Thus, prophetic personalities propose new, more plausible options.

My graduate professors at Abilene Christian University in 1968–69 were such prophetic personalities. I learned how to read Scripture to discern the author’s intent by exegeting the discourse within its historical and cultural context. I remember a brief, pre-class statement by Dr. Abraham Malherbe when he picked up a Bible by the teacher’s podium and used it to illustrate a typical “Church of Christ” Bible: The wear on the pages illustrated that the book of Acts and General Epistles had been thoroughly used but the Gospels were relatively untouched. I remember thinking, “How am I reading the Bible? What is my hermeneutic?” I recall a similar incident when reading a comment on one of my research papers about a theology of animistic beliefs in Dr. Thomas Olbricht’s class on Philosophy of Religion. He scribbled, “I perceive that you have a deeper understanding of animism than Christianity.” Dr. George Gurganus, the first professor of missions in Churches of Christ, challenged me to plant “indigenous churches” and contextualize the message of the Good News of the kingdom of God. I realized that I had selectively read the Bible rather than allowing it, as a narrative of the work of God, to form my life. How was I to read the Word of God? How was I to reflect the character and mission of my God?

During this time, prophetic voices, like those of Carl Ketcherside and Leroy Garrett, challenged us to rethink our heritage in terms of the original intentions of Stone and the Campbells and called for greater grace and unity. An example is Carl Ketcherside’s sudden and heartfelt conversion on a trip to Ireland.10 Ketcherside had been a major voice within the anti-institutional segment of Churches of Christ. As editor of the Mission Messenger, he argued against the development of Christian colleges and the use of full-time preachers and debated these issues with leaders like G. C. Brewer and G. K. Wallace. However, he experienced a sudden transformation during a preaching trip to Ireland, where he visited the Presbyterian Church where Thomas Campbell preached before his journey to America.

After entering the church Ketcherside noted an old bronze likeness of Thomas with a plaque that read “Prophet of Union.” He planned to speak that evening on Ephesians 2:14: “For He is our peace who hath made both one, and hath broken down the middle wall of partition between us.” Throughout that day the words “For He is our peace” reverberated in his mind. As he spoke that evening, he realized that he was speaking more to himself than to his audience. He returned to Belfast that evening and walked two miles through a strong snow storm to reach the house where he was staying. His thoughts kept returning to Thomas and Alexander Campbell and their goal of restoring the unity of all believers. Convicted both by the words of the plaque and by his own sermon, he acknowledged what he would call his own “sectarian spirit.” As he read Revelation 3 the following morning, Ketcherside was deeply touched by the Lord’s message to the church at Laodicea: “For you said, I am rich, I have prospered, and I need nothing, not realizing that you are wretched, pitiable, poor, blind, and naked” (v. 17). As this forty-three-year-old preacher read the words of Jesus, “Behold. I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come into him and eat with him and him with me” (v. 20), he did something that he had never done. He asked Jesus into his heart! From that moment he had a completely different approach to life, to worship, to Christianity, and to ministry.

He became part of what some called the “progressive movement” that emerged in the 1960s and preached and spoke to Churches of Christ, Christian Churches, and Disciples of Christ.11

During this period of disequilibrium, my hermeneutics and theological convictions were nuanced and shaped through the experience of learning a new culture and language as a church-planting missionary first in Uganda and then among the Kipsigis people of Kenya. Over a 14-year period my wife Becky and I learned in community with not only our American co-workers, Fielden and Janet Allison and Richard and Cyndi Chowning, but also with a maturing national Kipsigis leadership. When the first six people were baptized in a village called Chebongi, across the valley from our home, we realized that something special had happened: We had planted our first church among the Kipsigis! This realization led us to ask some core biblical questions: What is the meaning of church? How does a church live as God’s distinct missionary community in this culture as explained in their language? In response, we spent the next three months studying the book of Ephesians, allowing this missionary letter to shape our model of ministry formation. Over the years we were driven by cultural realities to ask questions that we would never have asked in North America, specifically: How do we communicate the kingdom of God in this largely animistic culture? How do we read Scripture with an ear toward the relationship between God and the gods in the Old Testament, Christ and demons in the Gospels, and Christ and the principalities and powers in Pauline literature so that we teach and minister effectively to those in bondage not only to their own cultural beliefs but also to the power of Satan? Ministry in Africa thus served to de-secularize my Christo-secular heritage!

How does a church live as God’s distinct missionary community in this culture?

When we returned to the United States in 1986, the Churches of Christ were entering a stage that Wallace would call “cultural distortion.”

The Period of Cultural Distortion

During cultural distortion, new options confront old ways as people seek resolutions to the tensions of society. Culture is in a state of flux. Old conceptions are seen as increasingly incomprehensible and continually called into question. Prophets then challenge the assumptions that, in their understanding, fail to reflect the kingdom of God.

Our family returned to the United States in 1986, and I began my teaching ministry at Abilene Christian University during what I would describe as a crucial time in the history of Churches of Christ. A series of books challenging Church of Christ sectarianism were coming off the press. These books called for a new biblical hermeneutic and described an implicitly secular way of living embedded in our forms of religion. The year 1988 was a water-shed year with the publication of Illusions of Innocence by Richard Hughes and Leonard Allen, The American Quest for the Primitive Church edited by Richard Hughes, Discovering Our Roots: The Ancestry of Churches of Christ by Leonard Allen and Richard Hughes, and The Worldly Church by Leonard Allen, Richard Hughes, and Michael Weed.12 Reflecting on these writings, Mark Noll said: “The project they unfold is nothing less than a full-scale, rigorous, and critically informed investigation of the notion of ‘restoration,’ the controlling principles of the Churches of Christ since their inception . . . , that is, attempts to cut back through the corruption built up over centuries in order to recover the pristine purity of Christian faith and practices on the model of the church’s early period.”13

The most prophetic of these publications is The Worldly Church: A Call for Biblical Renewal. The authors assert that the “scandal of the cross” has been replaced by salvation by human obedience, which has secularized the life and activities of what should be God’s covenant community. They write, “The things that matter most to the world often set the agenda for the church. In virtually every age, those who call themselves the church gradually take on the shape and color of the culture, enshrining its idols, sanctifying its values, and blunting the scandal of the cross.”14 The outward forms are adored but the inward essence humanized.

While writing this article for Missio Dei, I was struck by the influence of Leonard Allen’s The Cruciform Church: Becoming a Cross-Shaped People in a Secular World. No other book of a Restoration heritage has so formed who I am! The sections of the book critique (1) the way we read Scripture; (2) the way we view God, (3) the place we give to the cross of Christ, (4) our stance in the “world”, and (5) our portrayal of Christ-like character. Throughout the book Allen asks two significant questions: “ ‘What have we been?’ and ‘What does God through Scripture call us to become?’ Both questions are essential. In the interplay between them we will find new direction and identity.”15 I took Allen’s class framed around this content in 1986 immediately after returning from 14 years as a church planting missionary in East Africa. The class and later the book helped refine the re-theologizing that occurred during my years in Africa and guided me to find my place in God’s mission in North America!

These renewal messages have eroded old paradigms, contributing to the development of a “cultural distortion” during which Churches of Christ are declining. No longer is salvation understood as merely a “five-finger exercise” of hearing, believing, repenting, confessing, and being baptized. Communicating the gospel in searchers’ homes using the Jule Miller Filmstrips, organized around the Patriarchal Age, the Mosaic Age, the Christian Age, God’s Plan for Redeeming Man, and History of the Lord’s Church, seems both inadequate and inappropriate—far too sectarian. Jeff Childers, Doug Foster, and Jack Reese, in The Crux of the Matter: Crisis, Tradition, and the Future of Churches of Christ, define the disequilibrium: “The sense of stability and certainty from the early and middle years of the twentieth century is largely gone. Our papers have polarized, lectureships attract increasingly narrow audiences, and preachers who are influential in one segment of the churches are often unknown or demonized in others. While there is still an amazing consensus on many teachings and practices, you can never be sure about what you’re going to get when you visit a congregation in another place.”16 Thus Churches of Christ, who were the fastest growing religious group in the US during my teenage years, have ceased to grow, have lost their cohesion, and are rapidly declining. Many have began attending more vibrant community and Bible churches that share their developing sentiments. Others have became disillusioned with Christianity and either overtly or covertly have fallen into the secular or even pantheistic ways of living and believing.17

Churches of Christ are declining during a period of cultural distortion.

Wallace writes that if revitalization does not take place, feelings of disorientation will increase with resulting instability leading to gradual cultural disintegration. The populations of disintegrating societies can die off, splinter into autonomous groups, or be absorbed into larger, better integrated societies.18 With this in mind, we ask: Is renewal possible? Is there hope? Are there ready ears to hear the message of God’s prophets? What patterns of renewal are being proposed?

The Period of Revitalization

During this contemporary period, I discern three paradigms for renewal, each having its own theological assumptions and practices. These different, yet sometimes similar, movements are (1) “Return to the ‘Old Paths,’ ” (2) “Organize and Manage,” and (3) “Faithful Presence and Gracious Hospitality.”

“Return to the ‘Old Paths’”

To some the first impulse when facing disintegration and demise is a return to the “Old Paths.” A contemporary proponent is Michael Shank with his book Muscle and a Shovel.19 The book is a testimony of Shank’s conversion from a nominal Baptist heritage to become a member of the Churches of Christ. The journey began when a coworker, based upon the reading of 2 Thess 1:6–10, asked, “Have you obeyed the gospel of our Lord?” Searching for this “gospel” and how to “obey” raised questions about the Sinner’s Prayer, instrumental music, the development of denominations, and the organizational structure of the early Christian church. Shank responded to challenges to the hermeneutics and sectarian orientation of his book by saying: “There should be no arrogance in our brotherhood. Some have claimed that this humble work is trying to bring people back to the 1950s doctrine. Dear friends, I am so sorry for I have missed the mark. I was not trying to bring us back to the 1950s. I was trying to bring us back to 33 AD. Our Lord purchased his one church with his own precious blood.”

“Organize and Manage”

A second, more prevalent, response to disequilibrium is to default to the management impulses of culture and to organize the church for “success.” This model is instinctive, not because of biblical precedent, but because it fits the organizational impulse of North America. The goal is frequently to become a growing megachurch with vast resources and high influence.

Church is envisioned as an organization to be managed rather than a community on mission with God. The focus is on managing projects and events, not personally walking with searchers within neighborhoods and networks and guiding them to become disciples of Jesus. The projects and events are coordinated by a paid staff rather than equipping lay leaders for these ministries. Strategic planning sets the course for the church rather than prayer and fasting and the discernment of God’s leading through the Holy Spirit. A hierarchy, whether formal or informal, is deemed necessary to implement the plans of the church rather than an understanding of the giftedness of all believers. Ministry leaders focus on giving information rather than modeling mission and inviting new Christians to imitate what they are doing. Within this structure the preaching minister becomes the most important leader of the church—the person people come to hear.

On a practical level this “manage and control” approach tends to negate the work of the Holy Spirit. The church plays the role of a vender of religious goods and services and invites people into the organization to receive these blessings. Church success is measured by attendance, bricks, and cash (the ABC’s of successful church growth) rather than the more difficult metric of “being transformed into the likeness of Christ” by reflecting “the Lord’s glory” (2 Cor 3:18). As David Fitch says, “There are Empire builders and then there are planters of the Kingdom and between the two is a huge difference.”

There are seeds of renewal, however, in some of these movements. One example is the Willow Creek Community Church, which published an introspective analysis of the relationship between church involvement and spiritual growth, called Reveal: Where Are We? They discerned four successive stages of spiritual development: (1) exploring Christ, (2) growing in Christ, (3) close to Christ, and (4) Christ-centered. Their findings were surprising: While Willow Creek was effectively helping people come to Christ and take initial steps as Christians (stages 1 and 2), they were not adequately equipping these disciples to grow into mature Christians (stages 3 and 4). Some of the most mature Christians could not find a place for ministry within the church and were looking for alternative communities which emphasized deeper spirituality.20

These shocking realizations led Willow Creek to determine which activities and programs would lead to greater spiritual growth. In the book Move: What 1,000 Churches Reveal about Spiritual Growth they discerned that participation in church projects or events does not predict or drive long-term spiritual growth. While these activities have some influence during the earlier two stages, personal spiritual practices, including prayer and Bible reading, have far more influence on long-term spiritual growth.21

This study suggested four “best practices” for spiritual growth: (1) Rather than providing multiple opportunities for personal involvement, newcomers are provided a “pathway . . . designed specifically to jumpstart a spiritual experience that gets people moving toward a Christ-centered life.” (2) “They embed the Bible in everything. . . . These churches breathe Scripture. Every encounter and experience within the church begins with the question, ‘What does the Bible have to say about that?’” Church leaders model a life based on the answers to that question. (3) “They embrace . . . discipleship values as part of their identity” and hold “people accountable for changing their behavior—for becoming more Christ-like in their everyday lives as a reflection of their faith.” (4) “Best-practice churches don’t simply serve their community. They act as its shepherd, becoming deeply involved in community issues and frequently have members serving in influential positions with local civic organizations. They often partner with nonprofits and other churches to secure whatever resources are necessary to address the most pressing local concerns.” They desire to move from consumer churches seeking to satisfy the felt needs of members to equipping churches “consumed with making disciples.”22

The movement from “organize and manage” to making disciples on mission with God is very difficult. This renewal is possible only when God grasps the hearts of discerning leaders who develop discipling practices that lead to spiritual renewal.

“Faithful Presence and Gracious Hospitality”

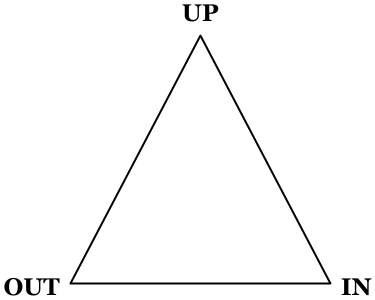

The third response to disequilibrium and demise is “faithful presence” and “gracious hospitality”—a missional response focused on growing as disciples of Christ within Spirit-formed communities with God’s mission flowing through us to the world. Stated simply, disciples are nurtured to live UP in relationship to God; IN in community under God; and OUT on mission with God in both worship gatherings and missional communities. While “organize and manage” reflects the impulses of our culture, “faithful presence and gracious hospitality” are counter-cultural perspectives reflecting the nature of Christ, who “became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14). In describing this response, I define “faithful presence” and then relate these understandings to “gracious hospitality.”

The third response to disequilibrium and demise is “faithful presence” and “gracious hospitality”—a missional response focused on growing as disciples of Christ within Spirit-formed communities with God’s mission flowing through us to the world. Stated simply, disciples are nurtured to live UP in relationship to God; IN in community under God; and OUT on mission with God in both worship gatherings and missional communities. While “organize and manage” reflects the impulses of our culture, “faithful presence and gracious hospitality” are counter-cultural perspectives reflecting the nature of Christ, who “became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14). In describing this response, I define “faithful presence” and then relate these understandings to “gracious hospitality.”

Faithful presence is walking with God, basking in his love and holiness and living by the power of the Holy Spirit. Faithful presence is like marriage in which the husband and wife faithfully care for each other (Eph 5:25) or a family in which parents lovingly care for and nurture their children who then faithfully care for their parents at a later stage of life.

Faithful presence is incarnational: God comes to us in multiple forms and dwells among us. We, in turn, grow to dwell with him.

This presence is illustrated by God’s walking in the Garden of Eden after Adam and Eve sinned, calling out, “Where are you?” (Gen. 3:9).This question is a metaphor of God’s faithfulness: Because he formed us in his nature, he loves us unconditionally, is always coming to us, sacrificed his Son for us, and indwells us through the Holy Spirit.

Faithful presence is illustrated by Moses’ face radiating God’s glory after he dwelled with God 40 days on Mt. Horeb (Exod 34:29-34; cf. 2 Cor 3:7-18) and Moses’ pleading statement to God, “If your Presence does not go with us, do not send us up from here” (Exod 33:15), when the Israelites waiting for him at the foot of the mountain returned to the pagan customs of their Egyptian heritage.

The most explicit expression of God’s presence is Jesus Christ, who came into the world not only to die for our sins but also to show us how to live. This theology of incarnation is encapsulated in the name Immanuel. This Hebrew name עִמָּנוּאֵל (⁽immānû ⁾ēl), meaning “with us [is] God,” consists of two Hebrew words: אֵל ( ⁾ēl, meaning “God”) and עִמָּנוּ (⁽immānû, meaning “with us”). Who then is Jesus? The answer revealed by the incarnation is: Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man in one person. In other words, He is God incarnate. The incarnation of God in Christ shows just how far God is willing to go to identify with those he desires to serve and to save.

Before Christ ascended, he left a promise. “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8). The book of Acts describes the story of the church faithfully operating under the power of the Holy Spirit. The first Gentle church, during a time of prayer and fasting, was commissioned by the Holy Spirit to send out Barnabas and Saul “for the work to which I have called them” (Acts 13:1–4).

Thus “faithful presence” is distinctively Trinitarian. The church lives in relationship with the Father, models the life of the Son, and is being empowered by the Holy Spirit.

James Hunter says that this incarnation

is the only adequate reply to the challenges of dissolution; the erosion of trust between the word and world and the problems that attend it. . . . For the Christian, if there is a possibility for human flourishing in a world such as ours, it begins when God’s word of love becomes flesh in us, is embodied in us, is enacted through us and in so doing, a trust is forged between the word spoken and the reality to which it speaks; to the words we speak and realities to which we, the church, point. In all, presence and place matter decisively.23

As we nurture our souls, we are called to dwell in God’s presence—in our homes, our work contexts, and places of recreation; in our community of faith worshipping in the Spirit and encouraging one another to faithfulness; and in missional communities (or small groups) in specific neighborhoods and networks, inviting searchers to participate with us to experience living in God’s presence. Living in God’s presence is breathing in the Spirit to live cruciform lives as witnesses to the gospel (Rom 1:16–17), distinctively Spirit-filled in our secular, increasingly pantheistic culture!

“Gracious hospitality” forms the character of our communities—both in our worship gathering and in our missional communities. Gracious hospitality leads us to invite people into our lives, to “come and see” the presence of God. John’s Gospel records the enthralling story of two of John’s disciples following Jesus when they heard that he was the “Lamb of God.” Jesus turns and asks, “What do you want?” Not knowing what to say, these disciples respond, “Teacher, where are you staying?” Jesus says, “Come and . . . see,” and they spent the day with him (John 1:35–39). Andrew, one of the two, then called his brother Simon to “come and see” the one that he now knew to be the Messiah. The next day Jesus invited Philip, “Follow me.” Realizing that he had just met the Messiah, Philip told Nathanael that he had “found the one Moses wrote about in the Law, and about whom the prophets also wrote—Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph.” “Nazareth! Can anything good come from there?” Nathanael asks. Philip simply says, “Come and see.” As Nathanael heard Jesus describe his character and how he had seen him under a fig tree before Philip had called him, he declared, “Rabbi, you are the Son of God; you are the king of Israel” (John 1:35–51). With power Jesus invited people into his presence to know and follow him.

“Come and see” is the essence of hospitality. It is inviting people to walk with us—to see if this Christ Way is the right way. “Come and see” means “Come and think, . . . come and examine the evidence, . . . come and follow and change your life.”24 Hospitality is inviting people into our lives to see Jesus. What would happen if the church was known as a community walking in the presence of God?

Four practical changes are needed to support this renewal. First, God is worshiped as sovereign Lord who renews his church through the interceding of his Son and his indwelling Holy Spirit. Second, leaders understand their purpose as ministers who equip God’s people for works of ministry rather than organizers of projects and events. They grow beyond seeking volunteers for church projects to equipping disciples “so that the body of Christ may be built up” (Eph 4:12). Thus the church focused on the mission of God equips and releases her members into God’s mission as illustrated by the Antioch church (Acts 13:1-4). Third, what God has done through the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ must flow through the veins of the church leading to vibrant gospel fluency. Our formerly secular vocabularies must reflect appropriate “words from God.” Fourth, the organization of the church must be simplified. When planting a new church, I suggest three primary structures—a worship gathering for teaching the Word of God, inspiration, and testimony about God’s mission; missional communities in neighborhoods and relational networks who live UP – IN – OUT so that the kingdom of God is locally visible; and missionary youth ministries focused on local middle and high schools. Teaching and nurturing, then, take place through equipped lay ministers within the missional communities of the local church. Thus the church will be equipped to minister personally, heart-to-heart, where members work, play, and live. Note, for example, new churches like the Redland Hills Church, Storyline Christian Community, Gentle Road Church of Christ, and Ethos Church.

The New Steady Stage

The final stage of the revitalization process, according to Wallace, is ideally a new steady stage in which the cultural transformation has been accomplished and the new system has proven itself viable.

It is hard to discern at this time what the new steady stage will be. Since Churches of Christ are locally organized, diversity and fragmentation are the tendency. I doubt that the “Old Paths” movement is sustainable because of its idealistic cultural roots as the “one and only” representation of the early Christian church. The “Organize and Manage” movement seems to be the most prevalent. Often, however, members of Churches of Christ tend to flow through these churches to more “successful” Bible churches, resulting not in a “new steady stage” but a stepping stone to a new heritage.

There is, however, real hope for innovative “organize and manage churches” who are called to intentionally mature disciples to become God’s missionary people. As mentioned earlier, the Willow Creek Community Church has intentionally sought such renewal. Also, Elaine Heath and Larry Duggins in Missional. Monastic. Mainline: A Guide to Starting Missional Micro-Communities in Historically Mainline Traditions envision missional communities that intentionally form at the edges of traditional congregations to prototype the new way of living UP, IN, and OUT within their neighborhoods and relational networks.25 The vital question, thus, is “How many ‘organize and manage churches’ have the spiritual imagination and courage to facilitate renewal?”

“Faithful Presence and Gracious Hospitality” is the most difficult movement of the three paradigms. Like the early Christian church, it relies on the power of the Holy Spirit to take root and flourish. However, like a mustard seed it can morph into “the largest of the garden plants and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and perch in its branches” (Matt 13:31–32).

Thus, answering the question, Is missional a fad?, requires both a personal and communal calling. We must personally, prayerfully nurture our souls to live UP—in relationship with God; IN—in community with other Christians and searchers; and OUT—in mission equipping disciples through imitative practices of prayer, discernment, and mission. Communally, we must live in God’s faithful presence while extending gracious hospitality to those around us.

We must live in God’s faithful presence while extending gracious hospitality.

These practices are easier described than implemented. I confess that during certain periods of my life I advocated for missional living without adequately living as God’s emissary. Accordingly, we must encourage and equip those in our community of faith to practice such faithful presence and gracious hospitality. Finally, this nurturing for missional must occur in our Christian universities and training ministries. Leonard Allen, now the Dean of the College of Biblical Studies at Lipscomb, writes, “I am trying hard at Lipscomb to rethink and refocus the way we train men and women for ministry—particularly with a turn toward making praxis an integral (rather than mostly peripheral) part” of theological education.26

I pray that this article will provide a model to both help us understand ourselves and renew our lives around walking in God’s faithful presence as his missionary people.

Remember this wisdom from T.S. Elliot:

The Church must be forever building, and always

decaying, and always being restored . . . .

But here upon earth you have the reward of the good and

ill that was done by those who have gone before you.

And all that was ill you may repair if you walk together in

humble repentance . . . .;

And all that was good you must fight to keep with hearts

as devoted as those of your fathers who fought to gain it.

The Church must be forever building, for it is forever

decaying from within and attacked from without.27

Dr. Gailyn Van Rheenen served as a church-planting missionary to East Africa for fourteen years, taught Missions and Evangelism at Abilene Christian University for seventeen and a half years, and is the founder of and facilitator of church planting with Mission Alive (http://missionalive.org). His books Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Perspectives, Communicating Christ in Animistic Contexts, and The Changing Face of World Missions (authored with Michael Pocock and Doug McConnell) are widely used by both students and practitioners of missions. He edited Contextualization and Syncretism, a compilation of presentations of the Evangelical Missiological Society. His website (http://missiology.org) provides resources for missions education for local church leaders, field missionaries, and teachers of missions.

† Adapted from a presentation at the Thomas H. Olbricht Christian Scholars’ Conference, Lipscomb University, Nashville, TN, June 8–10, 2016.

1 Mike Breen and Steve Cockram, Building a Discipling Culture (Pawley’s Island, SC: 3dm, 2011), 79–98.

2 Robert D. Putman, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon and Schuster), 2000.

3 Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (New York: Marlowe & Company, 1999), 4.

4 Breen and Cockram, 115.

5 Dan Kimball, The Emerging Church (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003), 248.

6 Ibid., 116.

7 Anthony F. C. Wallace, “Revitalization Movements,” American Anthropologist 58 (April 1956): 279; see also Gailyn Van Rheenen, Communicating Christ in Animistic Contexts (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 1991), 69–77.

8 Wallace, 268.

9 F. W. Mattox, The Eternal Kingdom: A History of the Church of Christ (Delight, AR: Gospel Light Publishing Company, 1961), 351.

10 See Scott Harp, “William Carl Ketcherside: 1908-1989,” http://www.therestorationmovement.com/_states/missouri/ketcherside.htm.

11 Leroy Garrett, “Ketcherside, W. Carl (1908-1989),” in The Encyclopedia of the Stone Campbell Movement, ed. Douglas A. Foster, et al., (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 446.

12 Richard T. Hughes and C. Leonard Allen, Illusions of Innocence: Protestant Primitivism in America, 1630-1875 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988); Richard T. Hughes, ed., The American Quest for the Primitive Church (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988); C. Leonard Allen and Richard T. Hughes, Discovering Our Roots: The Ancestry of Churches of Christ (Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 1988); C. Leonard Allen, Richard T. Hughes, and Michael R. Weed, The Worldly Church: A Call for Biblical Renewal (Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 1988).

13 Mark A. Noll, “Rethinking Restorationism: A Review Article,” The Reformed Journal 39, no. 11 (November 1989): 15.

14 Allen, Hughes, and Weed, 52.

15 C. Leonard Allen, The Cruciform Church: Becoming a Cross-Shaped People in a Secular World (Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 1990), 15. An anniversary edition (ACU Press, 2016) of this book was published and featured at the Pepperdine Lectureship with response essays by Sara Barton, Richard Beck, Lee Camp, Raymond Carr, Randy Harris, John Mark Hicks, Scot McKnight, and Jonathan Storment and a new final chapter entitled “Last(ing) Things.”

16 Jeff W. Childers, Douglas A. Foster, and Jack R. Reese, The Crux of the Matter: Crisis, Tradition, and the Future of Churches of Christ (Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 2002), 116.

17 Gailyn Van Rheenen, “Competing Worldviews: Why Can’t I See the Gospel Like You Do?,” http://missiology.org/4-worldview-types-and-the-hearing-of-the-gospel.

18 Wallace, 270; see also Van Rheenen, Animistic Contexts, 72.

19 Michael Shank, Muscle and a Shovel (Metropolis, IL: Michael Shank Ministries, 2011).

20 Greg L. Hawkins and Cally Parkinson, Reveal: Where Are You? (South Barrington, IL: Willow Creek Association, 2007).

21 Greg L. Hawkins and Cally Parkinson, Move: What 1,000 Churches Reveal about Spiritual Growth (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011).

22 Dave Jacobs, “Resources and Encouragement for Pastors and Church Leaders,” http://davejacobs.net/daves-book-review-of-move-what-1000-churches-reveal-about-spiritual-growth-greg-l-hawkins-and-cally-parkinson.

23 James Davidson Hunter, To Change the Word: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 241.

24 Tim Keller, “Come and See,” accessed July 12, 2013, http://sermons2.redeemer.com/sermons/come-and-see.

25 Elaine A. Heath and Larry Duggins, Missional. Monastic. Mainline: A Guide to Starting Missional Micro-Communities in Historically Mainline Traditions (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2014).

26 C. Leonard Allen, e-mail message to the author, July 9, 2016.

27 T. S. Eliot, The Complete Poems and Plays: 1909-1950 (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Jovanovich, 1980), 101.