Beginning publication in 1967, Mission was envisioned as “a journal of controversy” that would challenge the post-war rationalistic approach to theology that had developed within Churches of Christ in the 1950s and 1960s. With a younger, more worldly audience in mind, Mission operated at the intersection of Restoration theology, social evolution, and cultural diversity by addressing “grinding human needs” related to equity, poverty, peace, and political trust. Negative reactions to Mission’s direction highlighted the transition of Churches of Christ from a radical sect to a mainstream American religious institution. This process included a renewed appreciation for fundamentalism by conservative church leaders and the conflation of the political left with their theological opponents. In response to such criticisms, Mission turned from its original commitments to the “weightier matters” of social justice and instead exhausted its energies detailing more mainstream theological subjects.

In Mission’s September 1986 issue, public relations consultant and early Mission contributor, Walter E. Burch, reflected on what he called the journal’s “20-year odyssey.” Thinking out loud, he wondered how best to measure the importance of the publication’s voice within the Churches of Christ. Had Mission significantly influenced the fellowship? And if so, how? Had Mission advanced its proposals in a responsible manner? Was there enough depth to Mission’s original themes to sustain the enterprise? Should Mission itself become part of the mainstream institutional apparatus within the Churches of Christ?1

Unfortunately, with the publication of Mission’s final issue coming just fifteen months later, the opportunity for such a self-appraisal would not be fully realized. Still, for scholars, analysts, and other interested parties, Burch’s thoughts provide a practical framework through which to assess Mission’s legacy, especially regarding the sustainability of the journal’s initial features. While discussions touching on race relations, social justice, the anti-war movement, and political ideology received extensive coverage during Mission’s first several years, attention eventually shifted toward more traditional theological subjects and away from the “grinding human needs” of equality, poverty relief, world peace, and political trust.2

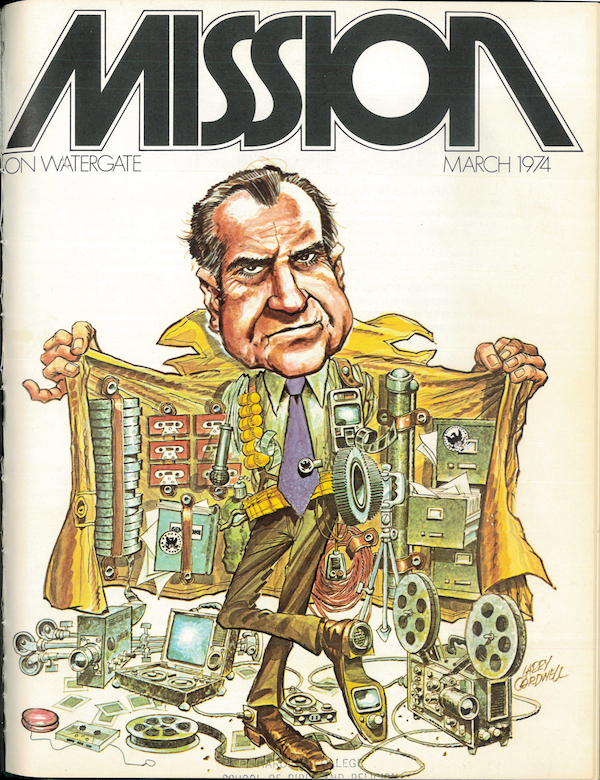

The apogee (or nadir, depending on one’s perspective) of Mission’s venture into questions surrounding such sociopolitical affairs was its March 1974 edition—“On Watergate.” The issue included a cover page editorial cartoon highlighting the personal corruption of Richard Nixon and that of his administration.

Figure 1: Cover of Mission (March 1974)

Figure 1: Cover of Mission (March 1974)

Perry C. Cotham, political science professor at David Lipscomb College (now Lipscomb University), referred to June 17, 1972—the date of the Watergate burglary—as possibly the “date of the death of both American public idealism and unwavering faith in her public institutions and officials.” Arguing that there was an inherent logical relationship between political action and its resulting moral implications, he encouraged Mission’s readers to “place [the Watergate] crisis in the context of genuine Biblical morality.” Cotham criticized both the Churches of Christ for the absence of such discussions in the fellowship’s publications and Nixon for moralizing on issues such as “faith, trust, belief, and spirit” that emphasized “pietism” over “Christian social ethics.” Worried that an uncritical reception of Nixon’s ‘theology’ by many Christians was “ ‘rendering unto Caesar’ more than [was] his due,” Cotham called for both a private morality (piety) and a public one (social ethics). He concluded, “Christian ethics are essentially social ethics—one cannot truly be in right relationship to God unless he is in right relationship to his fellowman.”3

Reader response was sharp. Thomas Langford, former Mission contributor, described the March cover as “tasteless,” “offensive,” and a violation of New Testament teachings about the relationship between the Christian and the government. While acknowledging that censure of Nixon’s behavior was warranted, Langford considered the issue’s cover to be “beneath the dignity” of what he called “redemptive Christian judgment.” One outspoken reader denied that the Nixon administration’s activities were “more sinister than anything previously encountered in this country” and chastised Cotham for going “to tasteless extremes to buttress [his] untenable position.” Still another, accusing Mission’s editors of participating in “a dishonest charade,” expressed grief “that [Mission] felt called upon to unleash [its] liberal political philosophy” on its diverse readership. Reflecting on first-century Christianity in a manner typically associated with twentieth-century restoration theology, one reader countered: “My gut level reaction to the whole political content of the issue is that we have come a long way, baby, since the time when Christians could fear God and honor the king—even when the king was Nero (or Nixon?).” Finally, one complained that she had just renewed her subscription for three years to what amounted to a “political propaganda sheet”—“We get that everywhere we turn, but we look to Mission for a change, for encouragement, to learn more about Jesus and to draw closer to God.”4

While the number of subscriptions to Mission had grown to over 3,000 by the end of its first year of publication and had risen steadily thereafter, the March 1974 issue would permanently marginalize the paper, beginning with an immediate decline in readership. Such a “negative response,” according to Robert Randolph, “indicated the shape of political sentiment in Churches of Christ.” While conservatives at large had never developed a significant taste for social justice, even progressive leaders had seemed to lose interest. Both had made themselves at home in an American subculture defined by conservative politics and a rejection of avant-garde activism. To survive in this prevailing environment, Mission turned aside from its roots of aggressive social commentary and instead focused on matters relating to so-called “Christian journalism.”5

These sorts of expectations for a more conventional approach to political theology would continue to gain traction within the fellowship in the years that followed. For example, two decades after the publication of Mission’s final issue, Church of Christ minister David A. Hester in his book Tampering with Truth: The New Left in the Lord’s Church6 argued for the favored status of conservative partisan politics within the Churches of Christ. While not representing a genuine theological cross-section of twenty-first-century thinking among the Churches of Christ, Hester’s approach nevertheless illustrates the influence that right-wing politics has held on the fellowship, especially in the American South.

Specifically, Hester linked leaders of what he called the “New Left” in the fellowship with the “extreme radical causes” of those on the political Left who had come of age in the 1960s. By conflating the two groups, he blurred the lines between theological matters and social ones, highlighting the extent to which many in the Churches of Christ had come to equate conservative politics with theological orthodoxy. Hester expressed this explicitly by describing what he saw as the uncanny resemblance between American political liberals and their theological counterparts in the Churches of Christ. In the process, he cataloged rather precise policy positions he deemed inappropriate for the faithful American Christian—opposition to the Vietnam War and support of black nationalism a generation earlier, as well as contemporary perspectives favoring more progressive social and economic policies than those that had been championed during the Reagan administration.7

Hester’s quarrel with “the New Left” extended to its historiography as well. He charged liberal scholars with practicing what he described as “revisionist history”—a supposed reinterpretation of the past in support of a so-called radical agenda. In the process, he also lauded conservative attempts to simply record, as he put it, “what actually happened.” His analysis revealed the incongruity of a conservative rejection of serious self-reflection within the Churches of Christ and Mission’s desire to create a culture of relevance in the fellowship by reassessing Scripture in view of ever-changing cultural dynamics.8

This friction is detected in Hester’s contempt for what he believed the Sixties had come to symbolize—namely, a departure from traditional civic and religious values. For example, he derided the attention given to the decade by historian Richard Hughes in Reviving the Ancient Faith: The Story of Churches of Christ in America.9 “In his 448-page work, Hughes devoted three chapters to the decade of the 1960s!,” Hester complained. In criticizing even the title of the monograph, Hester wryly observed that Hughes had in fact done “the brotherhood an unwitting service” by chronicling its “history of radicalism.”10

However, it was not only conservative church leaders who had rejected such progressive social values. Ironically, even less conventional leaders left the task of Mission behind, as the Churches of Christ prepared to advance into the twenty-first century. For instance, while acknowledging the role of the Churches of Christ in helping to alleviate social challenges in American communities, C. Leonard Allen, Richard Hughes, and Michael Weed in The Worldly Church: A Call for Biblical Renewal expressed concern that “meeting contemporary ‘needs’ ha[d] all but crowded out biblical theology.”11 While Mission had encouraged direct political involvement as a means of accomplishing important theological ends, Allen, Hughes, and Weed, while reflecting fondly on an earlier “radical sectarianism,” warned about the development of “political activism [as] the vital center of Christian faith.”12

Similarly, Mission’s own trustees ultimately exchanged the journal’s original philosophy for temporary survival in a fellowship that had grown comfortable with its place in mainstream American culture. While perceived by its critics as merely an outlet for the “disloyal opposition,” Mission had imposed self-limitations as well, as it evolved from “a journal of controversy” to a publication focused on more customary theological issues.13 Eventually, in announcing Mission’s demise, board president Robert Randolph summarized the periodical’s quixotic struggle to help focus the Churches of Christ on the “weightier matters” envisioned by its original contributors: “The energy for Mission came out of a time of ferment and change. The situation today is different. Things have changed in Churches of Christ and we recognize that much more needs to change. The history of Mission seems to be baggage that hinders us from being part of that change. The initial impulse may well have spent itself in a righteous cause, but it has spent itself nevertheless.”14

While appraising Mission’s legacy, Walter Burch echoed Randolph’s sentiments by describing the cultural environment of the late 1960s as an era of “crisis and promise, of frustration and courage, of ferment and seething discontent, of protest and intransigence.” The notions of crisis and promise also characterized the work of Mission itself. Although the journal had failed to substantially alter the ethos of twentieth-century Churches of Christ, it had rightly called attention to the distinction between missions and mission, as it scrutinized the church’s function in the world at large. Likewise, present-day Churches of Christ find themselves in a time of “frustration” and “discontent,” but with a missional opportunity—to be a fresh, raw voice for faith, good news, optimism, and a healthy restlessness. And the stakes could not be higher. In the words of twentieth-century Swiss theologian Emil Brunner, a favorite of Burch’s: “Where there is no mission, there is no Church; and where there is neither Church nor mission, there is no faith.”15

Brad McKinnon is Associate Professor of History and Christian Ministry at Heritage Christian University (Florence, Alabama). He is contributor to Reconciliation Reconsidered: Advancing the National Conversation on Race in Churches of Christ (ACU Press, 2016) and the George Washington Digital Encyclopedia (http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia).

† Adapted from a presentation at the Thomas H. Olbricht Christian Scholars’ Conference, Lipscomb University, Nashville, TN, June 8–10, 2016.

1 Walter E. Burch, “The Birth of Mission: Remembering the Way We Were,” Mission 20, no. 3 (September 1986): 10–11, 22.

2 Ibid., 10.

3 Perry C. Cotham, “Crisis in American Politics: Reflections on Watergate and the Rest of the Iceberg,” Mission 7, no. 9 (March 1974): 5–6, 11–12, 15.

4 “Forum,” Mission 8, no. 2 (Aug 1974): 28–30.

5 Robert M. Randolph, “Mission,” in The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement, ed. Douglas A. Foster, et al. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 533; “Forum,” 29.

6 David A. Hester, Tampering with Truth: The New Left in the Lord’s Church (Huntsville, AL: Publishing Designs, 2007).

7 Ibid., 6, 14–15.

8 Ibid., 89–90.

9 Richard T. Hughes, Reviving the Ancient Faith: The Story of Churches of Christ in America (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996).

10 Hester, 89–90.

11 C. Leonard Allen, Richard T. Hughes, and Michael R. Weed, The Worldly Church: A Call for Biblical Renewal (Abilene: Abilene Christian University Press, 1996): 8.

12 Ibid, 15.

13 “Focus Group Analysis of Current Condition of Mission Journal,” Walter E. Burch Papers, 1956–2006, Center for Restoration Studies, Brown Library, Abilene Christian University.

14 Robert M. Randolph, “To the Readers of Mission Journal,” Mission 21, nos. 5 & 6 (Dec 1987/Jan 1988): 43.

15 Emil Brunner, The Word and the World (London: Student Christian Movement Press, 1931): 108; quoted in Burch, 10.