Partnership is a way of describing the goal of mission, not a strategy for reaching a mode of mission in which collaboration is no longer necessary. This vision of partnership is essentially relational. As an introduction to the multifaceted missiological conversation about partnership, the authors narrate their experience in order to reflect upon the characteristics of the relationships that true partnerships in God’s mission comprise.

One Story about Partnership (Greg)

“Didn’t you say you wanted to work yourself out of a job?”

I had just asked Jeremy, my coauthor presently, if his newly formed mission team would consider joining our existing work in Arequipa, Peru. The two families that had been sent to Arequipa initially were beginning to imagine what our next step might be, and it had suddenly occurred to us that God was providing a path we hadn’t pondered: a second wave of Team Arequipa field workers.

Jeremy’s question was the response to our invitation that I had been hoping for. We were looking for coworkers who would be sensitive to the concerns about dependency and sustainability that had guided our mission work from the beginning. And since Jeremy, along with a few other prospective teammates, had visited Arequipa as students shortly after our arrival, they had heard us speak passionately about our intentions: to foster Peruvian leadership from day one, to prioritize the sustainability and reproducibility of the church on the basis of exclusively Peruvian resources, and, ultimately, to work ourselves out of a job as quickly as possible.

Yet, at that moment, though I was hoping for the question, I was not quite ready to answer it. Instead of working ourselves out of a job in about ten years, as we had projected, we had begun to imagine a transition at about six years that would move the church’s relationship dynamics toward an even stronger emphasis on partnership than we were able to achieve as “pioneer” missionaries. At the moment Jeremy asked me what had changed, all I knew was that working ourselves out of a job was no longer the goal. In fact, the idea seemed strange. It was the deepening of partnership, not the end of partnership, that would mark the maturation of new Peruvian Christians.

There are good reasons for thinking the way we did at first, not least that we were trained to cultivate indigenous (“four-self”) churches. This ideal involves financially, organizationally, evangelistically, and theologically independent churches—because dependency is its abiding concern. As well it should be. Nonetheless, the Western church’s need for repentance and caution in cross-cultural missions is compatible with a biblical theology of partnership, in which independence is not the end game. We’ll say more about this below; for now, back to the story.

The first few years of work in Arequipa were marked by strategic decisions meant to serve the sustainability and reproducibility of the local church’s life. We imagined the new Christians carrying on faithfully should the foreign missionaries suddenly (or eventually) depart, and we attempted to develop the habits and expectations that would serve that vision. We opted for a simple church lifestyle that would be feasible without the ongoing injection of foreign money and ministry: home or public-space gatherings, inclusive deliberation and decision making, hospitality- and family-oriented evangelism, and active recognition of all the gifts of the body. But the most important decision was not strategic. It was the result of a gift given to us by those who trained us—those who had participated in an anguished, decades-long discussion about the paternalism and ethnocentrism that shaped the attitudes of Western missionaries. That gift was a different starting place, a different disposition, a presuppositional humility rooted in keen self-awareness. In short, we are privileged to be the spiritual children of people who had already repented. The most important thing we did, therefore, was decide to be completely transparent about our dependence on our new brothers and sisters. We decided to be sincere as missionaries who knew that what once was considered strength—money, options, and US Americanness in general—was actually our weakness.

Of course, we were subject to the same cross-cultural difficulties as anyone else. The gift we inherited as young twenty-first-century missionaries was not immunity to our own cultural blindness or even better techniques for dealing with it. It was, rather, a disposition of confession: we were not only aware of and struggling with the implications of implicit US imperialism, economic disparity, and basic ethnocentrism; we also shared these difficulties openly with the Peruvians who heard us speak the gospel. We confessed our concern for the power dynamics that typically exist between Peruvians and North Americans, wealthy and poor, uneducated and educated. We confessed that our initial decisions and preferences as church planters might be detrimental to the church in the long run. And we confessed that we knew no other way to navigate such treacherous waters except by dependence on our Peruvian family.

Cross-cultural encounters engender awkwardness, even for the most adept communicators. Transparency, which is uncomfortable even in one’s own culture, adds a considerable complication. Therefore, openness about our uncertainty and vulnerability made for some disconcerting conversations, to say the least. Calling attention to the social dynamics in the room (and in the city and country) was sometimes like airing a family secret that everyone was trying to forget, as if ignoring it would make it untrue. Altogether, it was a trying way to make disciples and form churches. But it made possible something our strategic decisions could not: sincere spiritual friendships.

The power dynamics and social scripts that dominate our lives are as good as inevitable in most mission contexts, be they cross-cultural or not. These are the realities of our complicated relationships. Although we can grow in perceptiveness and learn to exercise wisdom, there are no strategic switches that, once flipped, free us from such complications. Nonetheless, in the frenzy to find the most effective practices, missionaries can overlook the fact that these issues are about relationships at root. God forbid I be taken to say that we should all just befriend each other. Best practices are the best we know to do, and we should do our best—unquestionably. But it was not a strategic insight that led to our decision to invite more foreign missionaries into the Arequipeño church despite our initial intentions. Sincere relationships changed our minds.

Our dear Peruvian friends, on whom we depended and who depended on us, were not abstractly a church on the way to indigeneity and self-realization. They, and we, were the church in Arequipa—a mixture of gringos and Peruvians, local and global, urban and urbanizing, with different gifts and different stories of God’s grace. We were partners in the kingdom, all of us, and it was no longer possible to imagine that the ideal somewhere beyond our faithful friendships and turbulent shared life was an artificial notion of “the Peruvian church” uncomplicated by the presence of foreign Christians.

So when Jeremy asked why we weren’t trying to work ourselves out of a job any more, what I didn’t have the words to say was that it had turned out the church wasn’t a project deemed to be complete once it was wound up and running on its own; the church was my friends and partners in the kingdom. The invitation was not to come take over “the missionaries’ job” but to become members of the church in Arequipa—spiritual friends with the disciples there.

The Rest of the Story (Jeremy)

About a year later, I arrived in Arequipa with my wife, Katie, for a two-month stay. We had a long list of questions. Answering them meant doing some of our own research. It meant asking the Team Arequipa field workers lots of questions. It also meant talking to the existing church about a future partnership.

The church was meeting as three groups in three different homes at the time, so we met with each group over the course of three Sundays. My question on behalf of the new families thinking about moving to Arequipa was simple: Do you want us to come? With one followup question: If you invite us to Arequipa, may we partner with you? I explained that we had been invited to consider moving to Arequipa by the missionaries, but that in the long-term we would be working with the Peruvian church. It would start with a slow learning phase, adapting to the culture and becoming functional in the language, all the while depending on friendly Peruvians to guide us through this new city. It would mean bearing with us through all the early bumps and missteps as we inched our way to making actual contributions to the work. It was only right to ask the Peruvian church if they wanted this.

They said yes.

Our transition began in 2014. Four new families moved to Arequipa over the course of the year. In early 2015, the original two missionary families moved away. As my wife and I approach our one-year mark in Arequipa, it strikes me just how dependent we’ve been on the Peruvian church for our entire learning phase.

Our relationship dynamics with the church are different from those of the original missionary families, because we came in as learners not only in terms of language and culture, but also in terms of church. The Peruvian church members are the experts when it comes to the Spanish language and Peruvian culture, and they are the experts when it comes to the life and mission of the Arequipeño church. We have the advanced theology degrees, and our sending churches designate us as “missionaries.” The Peruvian church, however, has a years-long head start on what it means to be a Christian community in Peru’s second-largest city. Despite the intentions and great effort of Team Arequipa’s first field workers, this is not a dynamic that they could have experienced. The power dynamics inevitably leaned in the missionaries’ favor. After six years, they had begun to experience interdependence and partnership, with unavoidable limitations. Their departure and our arrival set the stage for a deepening and maturing partnership—one we got to start experiencing during year one.

It strikes me just how natural the move toward interdependence has been. While some inevitable power dynamics still exist, our dependence on the Peruvian Christians up to this point is undeniable. As we build relationships with the local church, we are recognizing one another’s giftedness and reflecting on mission in light of who is a part of the church. We shared in vision-casting as a church. We wrote a mission statement together. Now we are partners, dependent on one another to live out our piece in the story of God’s mission in Arequipa. This is partnership. And we are just getting started.

Partnership in our story means being a member of the church in Arequipa and sharing a mission. We are experiencing partnership within our first year on the mission field, with plenty of years left in our commitment to see how it plays out. That’s the gift this transition has given us. There are and will be growing pains. What we’re experiencing on a small scale with just a few Peruvian church leaders will require patience and perseverance as the church grows. Relationships are beautiful and messy. This beautiful messiness is at the heart of God’s mission, and we look forward to sharing in it as interdependent US American and Peruvian Christians for years to come.

An Emerging Vision of Partnership

At times partnership seems like a way of discussing a cluster of issues in missions including sustainability and dependency, colonialism and globalization, long-term and short-term strategies, contextualization and indigeneity, and the professionalization of ministry. Each of these issues merits our undivided attention in its turn, but does integrating them as partnership contribute something more to our understanding? Reflecting upon the implications of our limited experience as Millennial missionaries, our essential observation is this: partnership is about relationships, so the character of our relationships in mission is what matters. Partnership is a relational category that forces the church to place each of its constituent conversations in the context of real relationships. We would like to suggest five relational characteristics that describe an emerging vision of partnership: such relationships are missional, organic, sincere, psychologically interdependent, and enduring.

Missional

God’s mission is the foundation of Christian theology. Churches build on this solid ground when they envision partnership as the intersection of the universal church’s participation in God’s mission and a trinitarian understanding of relationship. The sending of the Son and the Spirit that extends to the sending of the church constitutes our basic understanding of participation in mission. Concomitantly, the relationship of Father, Son, and Spirit into which the whole church is drawn by the reconciling love of God for the world constitutes our basic understanding of collaboration in mission. Two major conclusions about partnership emerge from the intersection of participation and collaboration.

First, all Christians are equal participants in mission. This is the essential truth of partnership. The mission being God’s, no participant claims ownership, and all participants stand on level ground. Furthermore, all participants are gifted by the same Spirit. Charles Van Engen states it beautifully:

In mission we are all co-workers—co-workers with God and co-workers with one another—on a global scale. Think of what this perspective could do to change church and mission relationships between older churches and newer missions in areas like Latin America, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, Africa, the Pacific—and places like Los Angeles, where I live. Regardless of how long our churches may have been present in the land, if we truly saw one another as mutually gifted co-workers in God’s mission, our perceptions of each other and our partnership relationship with one another could be transformed.

Second, all collaboration in mission—the purposes for which God sends the church—is partnership. Long-distance, intercongregational (or interinstitutional) relationships are usually in view in the missiological conversation about partnership. The relationship of long-term missionaries with the church members they disciple (as in our narrative) is rarely construed as partnership—much less the relationship of one church with another or one disciple with another in the same local context. Our difficulty seeing foreign missionaries as partners with national disciples is a vestige of paternalism, both a symptom and a continuing cause. But our difficulty recognizing partnerships as partnerships within a single, monocultural context exposes the theological mistake at the heart of the whole discussion: we do not see these relationships as partnerships, because partnership is a missiological concept, and we fundamentally do not understand these relationships as collaboration in mission.

Our narrative in the present article highlights the extent to which partnership in our experience has been about our collective gifts shared humbly in local mission, despite the cross-cultural complexities of our relationships. In this situation, we also mediate another type of partnership—that of our sending churches with local Peruvian churches. These two partnerships are practically very different, and it is reasonable to ask if the same sorts of relationships are in view. In turn, this question implies an even sharper one: do local, monocultural partnerships really belong in the same discussion with international partnerships? To hint at the underlying apprehension, we can put it like this: If everything is partnership, maybe nothing is partnership.

For those who deny the missional nature of the church, this apprehension must linger. But for those who affirm both that all Christians are equal participants in mission and, consequently, that all collaboration in mission is partnership in the missiological sense of the word, our narrative accentuates two implications. One, insofar as cross-cultural missionaries identify with their host culture, they become partners with disciples in their mission context by humbly sharing gifts in the same way that disciples in a common “home” context become partners by humbly sharing gifts as collaborators in mission. In other words, the ways that foreign missionaries deal with paternalism and relational complexity in cross-cultural situations turn out to be the same ways that Western churches must deal with the failure to see themselves as God’s missional people: by reimagining all of their relationships as fully mutual collaboration in mission and transforming them through practices of self-awareness, vulnerability, sincerity, submission, confession, repentance, and forgiveness. Two, insofar as partnership rightly entails the kinds of relationships that long-term, cross-cultural missionaries have the opportunity to form, the types of partnerships that are unable to foster such relationships deserve serious scrutiny. In other words, affirming that the same sorts of relationships should be in view across the spectrum of partnerships, the church must ask whether a given partnership qualifies as collaboration in mission according to its theological sense—and if not, whether it can be transformed or must be dissolved.

A lesser implication also deserves mention: partnership is not best limited to a discussion of financial arrangements. Money, to be sure, complicates relationships, especially cross-cultural ones formed in the aftermath of colonialism. Yet, the church’s theological imagination does not begin with money and resources. We need to relocate the important conversation about money in missions within a robust missional theology of partnership. Only then can the priority of God’s purposes guide our financial decisions.

Organic

Relationships do not develop simply because a mission strategy document says a missionary should build relationships or because two churches structure an agreement carefully in a memorandum of understanding. These sorts of structures can serve partnerships. Indeed, they have been the substance of many. Formal arrangements can, however, only imitate the kind of relationship that God’s life reveals and inspires; they are artificial. Relational partnerships are characterized by a process of growth; they are organic.

Relationships can mature, but like all organic life, they need time to develop. An artificial partnership, by contrast, attempts to put into place mechanisms that will ensure it starts and runs smoothly. The mechanistic metaphor is not inherently bad, of course, but it exposes the expectation that partnership will function as a whole (perhaps requiring adjustments) rather than maturing and eventually bearing fruit.

Furthermore, for partnerships to develop organically, partners must set aside their predetermined agendas so that each others’ input can set the course of the relationship. An organic relationship does not simply conform to preconditions, even theoretically sound ones. It is like the legend of the wise university architect who waited for students to wear paths in the grass in order to pave the sidewalks along those naturally occurring routes. It does little good to plot out the sidewalks in advance, even if they would be more linear, more logical, more cost-effective, or more timely. Often partners in mission attempt to plot the way forward without walking together for a time in order to discover the path. The journey along that preconceived pavement ends up being an exercise in insincerity. It is not the way the partnership would have gone had it been allowed to find its way organically.

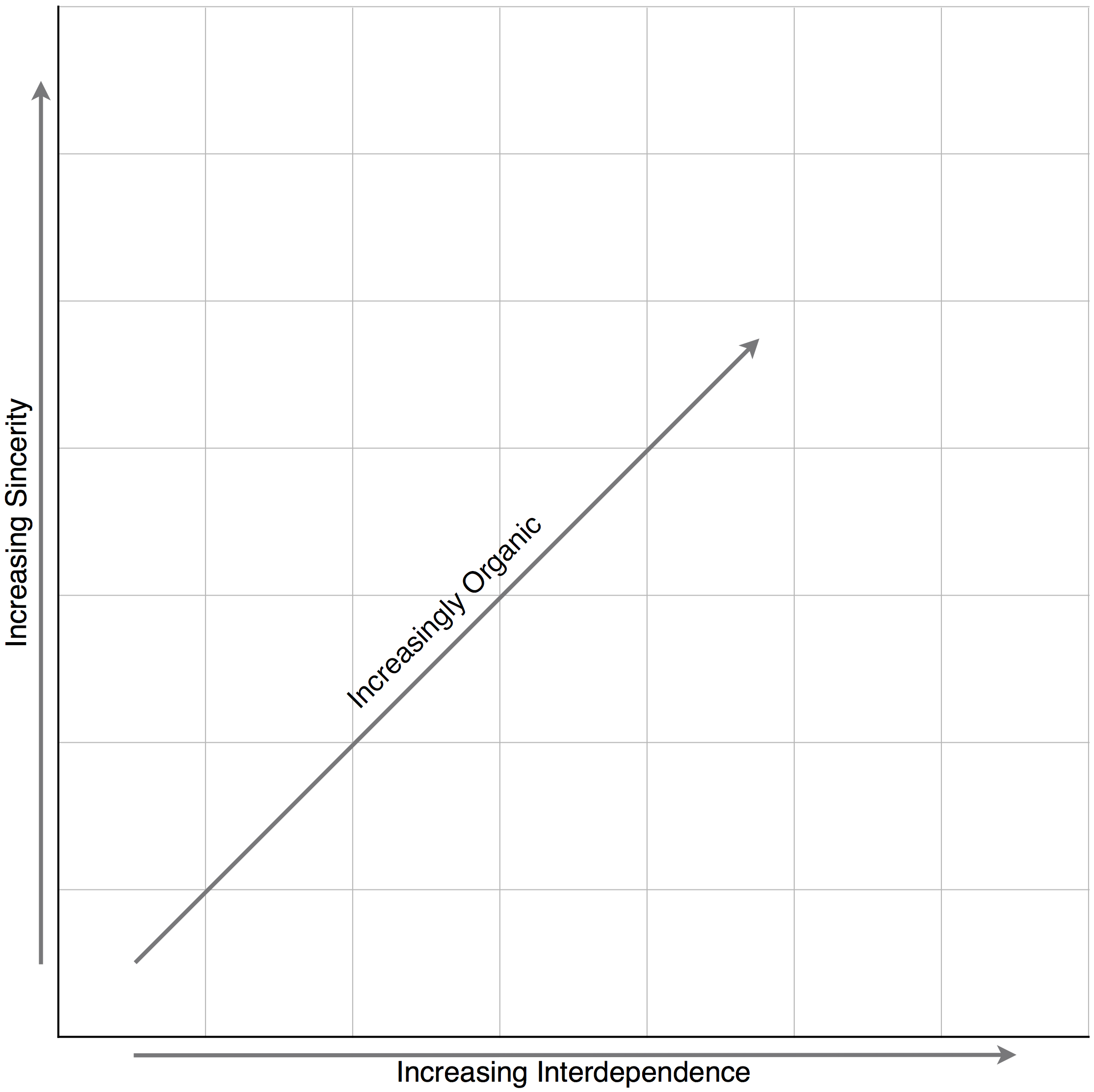

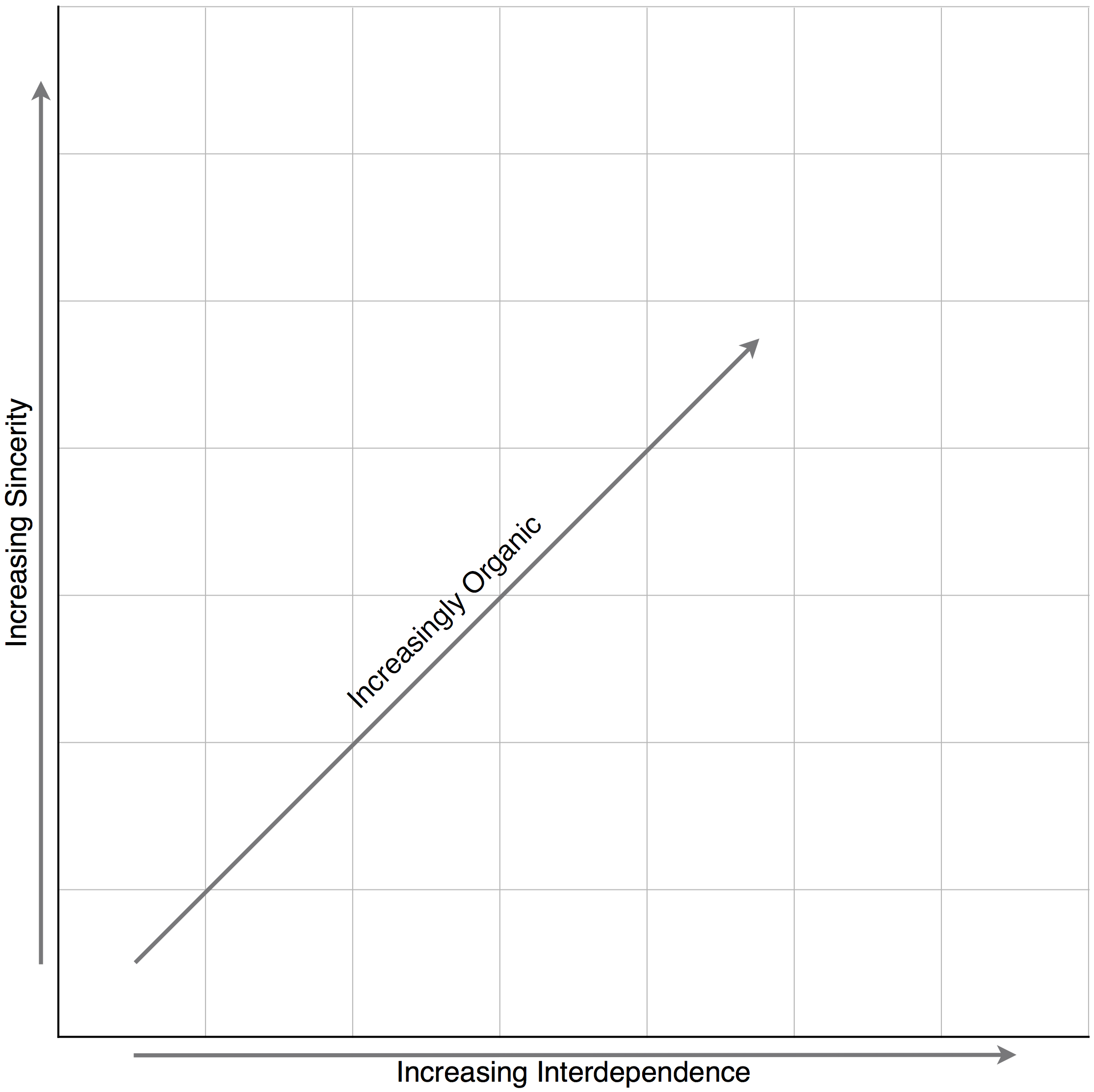

Taking interdependence as one coordinate for organic partnerships and sincerity as another, we can depict the degree to which a partnership is organic as a correlate of the two:

Figure 1

This invites a fuller understanding of what sincerity and interdependence entail in a missions partnership.

Sincere

The practice of identification, rooted in an incarnational theology of ministry and an increased anthropological acuity, remains one of the greatest gains of twentieth-century missiology. The burden of acculturation rests upon those who are sent, whose purpose is to relate meaningfully. Communication is one dimension of this purpose, but it is too limited to speak only of cross-cultural communication. While the observation that “everything that people do communicates” is comprehensive enough to get us to relationships through the back door, it is better to reorient the idea: relationships depend on good communication. Identification serves a relational end. The limits of identification, then, also have to do with our cross-cultural relationships—namely, their sincerity.

William Reyburn wrote a classic essay entitled “Identification in the Missionary Task,” in which he explores the limits of identification. Reyburn does not see these limits as cause for despair, of course, but as part of an apologetic for closing the relational gap as much as possible: “The basis of missionary identification is not to make the ‘native’ feel more at home around a foreigner nor to ease the materialistic conscience of the missionary but to create a communication and a communion.” This communion—koinōnia in New Testament terms—is the relationship of reconciliation that we seek. An important question remains, however: If identification serves the relationship, doesn’t sincerity about the limits of identification characterize the authentic relationship rather than signaling its inability to overcome some sort of obstacle? We do not approach mutuality by dissolving otherness but by embracing it.

Partnership, then, should be characterized by the identification that cultivates communication, but that communication ultimately serves the relationship by virtue of its forthrightness and transparency. Sincere partners do not attempt to communicate an image of themselves that hides their weakness (or their strength). It is a basic relational failure to feign invulnerability:

When missionaries don’t allow others to help them, they deny those others their dignity. In refusing to admit that they hurt and need help and support, missionaries effectively deny those of the host culture the chance to see themselves as people who have something to offer the missionaries. Relationships developed with this weighing them down will be one-dimensional because the missionary only gives and the indigenous people only receive.

Beyond this essential mutuality, it is especially important for Western Christians not to downplay the dynamics their cultural identity entails. They carry (whether they wish to or not) a latent imperialism and a great deal of privilege. Their confession and dependence on Majority World partners’ advice about how to deal with these complications not only affirms the partners’ dignity but creates a relationship that can deal with its complications openly and directly (in culturally appropriate ways). Where this sort of authenticity exists, a space opens for “sincere love” (1 Pet 1:22; philadelphian anupokriton) to do its work.

Interdependent

The view of foreign missionary presence that looks forward to the exit and absence of foreign resources, be they human or financial, often seems like a gradual (less abrupt), local version of the infamous “moratorium on missions” advocated in the late twentieth century. Robert Reese has recently shed light on the intention of the call for the moratorium. It was not, contrary to popular belief, a call for the end of Western participation on global missions. The author of the call for the moratorium, John Gatu,

recognized that independence was the way to true interdependence. Gatu saw the moratorium as allowing space for African leaders to take the reins of leadership without oversight. This was not, as some feared, an escape into isolationism, but a means of creating true interdependence.

The Western claims of interdependence at the time were deeply problematic, and Gatu believed a period of independence (free of “partnership”) was necessary for African churches to achieve the ultimate goal of interdependence with Western churches, a goal he shared with many who reacted against his proposal. This is a helpful clarification, but the question remains whether this sort of “independence” is a necessary precursor to authentic partnership.

Various streams of developmental psychology have theorized a three-stage progression in human relationships: dependence, independence, and interdependence. If cognitive and psychosocial models of relationship are an apt analogy for partnership in mission (as the language of interdependence in missiological discourse suggests), then we should understand the progression through independence to interdependence on those models’ terms. The bottom line of a sprawling interdisciplinary conversation is this: dependence, independence, and interdependence are a matter of self-construal (a view of the self in relation to others). Independence is not a matter of breaking free from the dependent relationship in order to exist apart from it but of a changing perception of the continuing relationship that results in new attitudes and behaviors. Because partnerships are human relationships, it is right to understand independence as a prerequisite for interdependence, but it is wrong to suggest that independence consists of the temporary dissolution of the relationship.

One particular insight from these psychological understandings of relationship is vitally important. The self-construal that leads to a developmental transition is not one-sided. Both parties must see the relationship differently, and it is especially the responsibility of the non-dependent party to perceive the dependent party’s emerging independence. Likewise, it requires leadership in an independent relationship to initiate a transition to interdependence. The implication for missions partnerships is that the Western church’s failure has not been its presence but its inability to construe itself differently in the relationship, as other than the provider of otherwise nonexistent abilities and resources. A missional theology of partnership, in which all God’s people are mutual partners, can heal this relational disease:

Paul’s concept of the gifts of the Spirit calls us to encourage an environment of mutuality and complementarity among the members. This involves a climate in which all members of the body together may participate in God’s mission of world evangelization. The concept of the gifts of the Holy Spirit, looked at globally, moves us toward wanting to foster healthy forms of interdependence, avoiding the creation of unhealthy dependencies. As David Bosch writes,

The solution, I believe, can only be found when the churches in the West and those in the Third World have come to the realization that each of them has at least as much to receive from the other as it has to give. This is where the crux of the matter lies. . . . We know that in ordinary human situations, genuine adult relationships can only develop where both sides give and receive.

Understandably, when Western churches fail to perceive themselves and their Majority World partners as independent, much less truly mutual, the reaction will be a call for the end of the relationship. This is a psychologically normal reaction in a developmentally stunted relationship. Furthermore, when this happens, it is unfair for Western churches to claim that all they want is interdependence and to criticize the reaction as isolationist. The call for a moratorium (in the broad sense or in the local strategic sense) is a response to the experience of an entrenched relationship. To borrow biblical language for one specific relationship, it is akin to divorce as a response to hardness of heart, which is an essential unwillingness to change (Mark 10:5).

Nonetheless, although the reaction is understandable, it will not do to redefine independence in these terms or to imagine that the temporary dissolution of missions partnerships is a step toward truly interdependent partnerships. That is not the way healthy relationships develop. Independence is a matter of mutual psychological development rather than literal isolation, and this process is what gives meaning to the relational descriptor “increasing interdependence.” The church should therefore capture a vision of partnerships as characteristically developing toward interdependence and seek to initiate the mutual changes in self-construal that will lead through independence to interdependence. Only then will partnerships bear the fruit of sharing all our gifts one with another for the sake of God’s mission.

Enduring

The final characteristic of our emerging vision of partnership is its enduring nature. Churches have too often treated partnership as merely a means to an end, such as planting churches or overcoming dependency. Indeed, some find it important to emphasize that “partnership per se is not the point.” And perhaps the missional characteristic of our vision aligns with this idea. Yet, even to say partnership is a means to God’s ends does not quite communicate the most wonderful thing about it.

Partnership is the reconciliation of God’s image bearers and, therefore, is itself the end. God’s purposes are not abstract tasks to be completed but a state of reconciliation with God and one another as participants in enduring purposes. To speak of partnership in mission, then, is to envision the reconciled body of Christ fully engaged in mission. This is what God is ultimately after—his reconciled image bearers carrying out together the work for which they were made. Partnership is eschatological. As such, it invites our present participation in a future reality. At present, it is a foretaste, not the consummation we await. We fitfully struggle for sincerity and slowly grow in maturity. But we do not give up hope, because our partnerships are born of God’s mission and in turn herald God’s enduring promise of renewed relationships.

From 2008 to 2015, Greg McKinzie served in Arequipa, Peru, as a partner in holistic evangelism with Team Arequipa (http://teamarequipa.net) and The Christian Urban Development Association (http://cudaperu.org). Jeremy Daggett joined the work in 2014. Greg and Jeremy are both graduates (MDiv) of Harding School of Theology, editors of Missio Dei, and fanatics about amazing Peruvian coffee (http://drinkluminous.com). Jeremy continues to collaborate in Arequipa, and Greg is a PhD student at Fuller Theological Seminary.

Bibliography

Cross, Susan E., Pamela L. Bacon, and Michael L. Morris. “The Relational-Interdependent Self-Construal and Relationships.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78, no. 4 (April 2000): 791–808.

Drath, Wilfred H., Charles J. Palus, and John B. McGuire. “Developing Interdependent Leadership.” In The Center for Creative Leadership Handbook of Leadership Development, 3rd ed., edited by Ellen Van Velsor, Cynthia D. McCauley, and Marian N. Ruderman, 421–27. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010.

Gaines, Stanley O., Jr., and Deletha P. Hardin. “Interdependence Revisited: Perspectives from Cultural Psychology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships, edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and Lorne Campbell, 553–72. Oxford Library of Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Greenfield, Patricia M., Heidi Keller, Andrew Fuligni, and Ashley Maynard. “Cultural Pathways through Universal Development.” Annual Review of Psychology 54 (2003): 461–90.

Guignon, Charles. On Being Authentic. Thinking in Action. London: Routledge, 2004.

Hodgins, Holley S., Richard Koestner, and Neil Duncan. “On the Compatibility of Autonomy and Relatedness.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22, no. 3 (March 1996): 227–37.

Johnson, Jean. We Are not the Hero: A Missionary’s Guide to Sharing Christ, not a Culture of Dependency. Sisters, OR: Deep River Books, 2012.

Komives, Susan R., Felicia C. Mainella, Susan D. Longerbeam, Laura Osteen, and Julie E. Owen. “A Leadership Identity Development Model: Applications from a Grounded Theory.” Journal of College Student Development 47, no. 4 (July–August 2006): 401–18, http://stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/LID-Model.pdf.

Lindholm, Charles. Culture and Authenticity. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008.

McKinzie, Greg. “What We Talk about When We Talk about Partnership.” Missio Dei: A Journal of Missional Theology and Praxis 6, no. 2 (August 2015): 5–10.

Moreau, A. Scott, Gary R. Corwin, and Gary B. McGee. Introducing World Missions: A Biblical, Historical, and Practical Survey. Encountering Mission. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004.

Myers, Bryant L. Walking with the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development. Rev. and updated Kindle ed. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2011.

Pocock, Michael, Gailyn Van Rheenen, Douglas McConnell. The Changing Face of World Missions: Engaging Contemporary Issues and Trends. Encountering Mission. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005.

Reese, Robert. “John Gatu and the Moratorium on Missionaries.” Missiology: An International Review 42, no. 3 (July 2014): 245–56.

Reyburn, William D. “Identification in the Missionary Task.” In Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: A Reader, 3rd ed., edited by Ralph D. Winter and Steven C. Hawthorne, 449–55. Pasadena: CA: William Carey Library, 1999.

Taylor, Charles. The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Van Engen, Charles. “Toward a Theology of Mission Partnerships.” Missiology: An International Review 29, no. 1 (January 2001): 11–44.