Greg McKinzie

This essay reviews the perspectives presented in two recent volumes, The Mission of the Church: Five Views in Conversation and Four Views on the Church’s Mission. The author explains and critiques each author’s approach in light of the double criterion of trinitarian theology and pragmatic consequence. The essay concludes by plotting the diverse perspectives in a graphic synopsis that highlights the need for a dialectical understanding of the church’s participation in God’s mission.

The recent publication of two books on the mission of the church provokes this essay, in which I will review both volumes and suggest a synoptic view of the perspectives they present. The first book—The Mission of the Church: Five Views in Conversation, edited by Craig Ott—features chapters by Stephen B. Bevans, Darrell L. Guder, Ruth Padilla DeBorst, Edward Rommen, and Ed Stetzer.1 The second book—Four Views on the Church’s Mission, edited by Jason S. Sexton—features chapters by Jonathan Leeman, Christopher J. H. Wright, John R. Franke, and Peter J. Leithart.2 Singly, each is a useful introduction to the multidimensional theological dispute about mission. Together, they complement each other, providing a fuller vision of the issues at stake. Before reviewing each work, I will briefly lay out the context of the question that both books aim to answer: What is the mission of the church?

This question has not arisen in a vacuum. Indeed, the question itself is problematic in view of the historical and theological shifts that have precipitated the current discussion. The title of this essay employs a Latin phrase that has come to symbolize the major fault line in the discussion: missio ecclesiae (the mission of the church) is distinct from missio Dei (the mission of God).3 The conceptual differentiation, which emerged in contemporary missiology from an effort to relocate the church’s mission in God’s own life and work, ironically betokens the great difficulty of articulating just how, in practice, the church’s life and work relates to God’s. For all the theological heft of the claim that the mission is God’s, churches must still give an account of what they do and, in particular, how that relates to God’s mission. In my view, the importance of this task can be measured in proportion to the church’s ability to go on doing whatever it will do in the name of its mission, regardless of any reference to God’s mission. In other words, if the claim that the mission is God’s makes no difference for what the church does in “mission”—if the church would go on doing the same things in any case—then we have yet to understand how missio ecclesiae and missio Dei truly relate.

This is a properly theological problem, not only in that missio Dei is a trinitarian doctrine but also in that whatever one might say about the mission of the church, the crux of the matter is that one must account for God’s being and act. Mission is theological all the way down; if not, “the mission of the church” ceases to be either really mission or really of the church. The criterion with which I read these essays on the mission of the church, then, is thoroughly theological. At the same time, my criterion must be practical: at the end of the day, mission is an event. Mission happens. This happening, this mission, in the life of the church must be related to God’s own mission. Yet, although I say practical, I do not say mission is a practice, or even an action. Rather, by practical I mean pragmatic, in the philosophical sense—as in, concerned with the question, “What concrete practical difference would it make if my theory were true and its rival(s) false?”4 To speak of the mission of the church is to grapple with imminent realities pertaining to God, the church, and the world and their actual interactions on the ground. With this double criterion I turn to my reviews.

The Mission of the Church

Craig Ott’s introduction to the discussion is quite useful despite its brevity (or perhaps because of it!). It provides historical context for the discussion by way of a brief overview of the Mainline Protestant/Ecumenical, Roman Catholic, Evangelical, and Eastern Orthodox perspectives to follow. These “approaches” are respectively labeled “prophetic dialogue” (Bevans—Roman Catholic), “multicultural and translational” (Guder—Mainline Protestant), “integral transformation” (Padilla DeBorst—Evangelical), “sacramental vision” (Rommen—Eastern Orthodox), and “evangelical kingdom community” (Stetzer—Evangelical). Each author addresses the others’ perspectives in short response chapters at the end of the book.

Ott does not attempt to mediate, synthesize, or extrapolate—his role is to frame the discussion and select the participants. These decisions are significant, however, as both the strengths and limitations of the book hinge on the contributors’ answers to the issue as Ott frames questions about it: “How are we to understand the mission of the church?” becomes “What precisely is the missionary nature of the church? What are those purposes for which God sends the church into the world, and how is the church to fulfill them? In what ways is the church to be an agent or sacrament of God’s redemptive purposes for the world?” (ix–x). Not only does the meaning of alternative answers arise from the particularity of the authors’ perspectives, but one’s overall view of the problem is a function of which perspectives are included and excluded. The selection of respondents sheds light from different angles, which perhaps also draws attention to the other angles that are absent in this volume (and to the benefit of reading it alongside the other volume reviewed here). It matters a great deal, for example, that Ruth Padilla DeBorst brings both a Majority World and a female perspective. Likewise, the inclusion of Catholic and Eastern Orthodox perspectives in answer to a question that has taken shape in a primarily Protestant and Evangelical context is of consequence. Space is always limited, and such decisions are never easy, precisely because we must question them once they are made. As it stands, I find the range and quality of perspectives Ott has assembled to be quite compelling.

In the first chapter, Bevans concisely articulates the prophetic dialogue approach that he has developed extensively elsewhere. Those familiar with Bevans’s work will quickly recognize that one of the book’s achievements is the distillation of extensive literature into fairly concise chapters, which in turns makes comparison on key points far more convenient. The economy of each author’s contribution does not oversimplify their perspectives but rather helps to unclutter them. Bevans is clear from the first sentence that the question is how “to think about and engage in the Triune God’s mission of salvation in creation and history” (3). Prophetic dialogue is a synthesis of mission “as participation in the life and mission of the Triune God,” “as engaging in the liberating service of the reign of God,” and “as the proclamation of Jesus Christ as universal Savior,” (4) which Bevans takes to correspond to Orthodox, Ecumenical, and Evangelical emphases. In this sense, he has already attempted to account for the major streams of thought that the other chapters will represent, even if they do not fall exactly along the lines Bevans assumes.

The greatest strength of the prophetic dialogue approach is its dialectical nature, what Bevans calls “Catholicism’s ‘both-and’ character” (5). Mission is both prophecy and dialogue but also both a way “to think about and engage in the Triune God’s mission” (3) and a way “to think about and practice mission” (5). As my trinitarian-practical criterion suggests, the ability to maintain the latter tension (God’s mission and the church’s practice) is vital. It remains to be seen just how Bevans does so. The prophecy–dialogue tension is the chapter’s main thesis, of course. Mission is “a kind of continuum with dialogue on one side and prophecy on the other. Each context determines where the emphasis will be placed as the church engages in its missionary work” (9). On one side of the continuum is dialogue: “a basic attitude, indeed a kind of spirituality that underlies every aspect of mission”—“our basic stance is openness, an attitude of respect, listening, and docility (i.e., teachableness)” (6). On the other end is prophecy: “mission is ultimately about sharing the good news of God’s reign with the peoples of the world” (7). Yet, prophecy is a holistic endeavor, both nonverbal and verbal. On the one hand, it is “incarnated in the witness” (7) of Christians, so that “church communities are signs of the already present reign of God and give testimony to the merciful, life-giving, and true God revealed in Jesus” (8). On the other hand, Christians also “speak forth a message of encouragement and hope” and “speak out in all sorts of ways against the evil in society” (8). This essential tension established, Bevans summarizes “six elements or practices of mission, each of which has a dialogical component and a prophetic one” (10). The titles of these are fairly straightforward if one keeps in mind Bevans’s Catholicism: (1) witness and proclamation; (2) liturgy, prayer, and contemplation; (3) justice, peace, and the integrity of creation; (4) interfaith, secular (and ecumenical) dialogue; (5) inculturation; and (6) reconciliation.

Bevans next turns to “Trinitarian Foundations,” followed by “Scriptural Foundations.” By his own admission, the latter—passages from Luke and Paul that Bevans takes to illustrate mission as prophetic dialogue—need further work. I will focus here on the way he unpacks the claim made under the former heading that “much more deeply, the practice of prophetic dialogue is the full participation in God’s trinitarian life and mission” (13). This turns out to be an essentially pneumatological claim. Bevans develops it in relation to the Spirit’s general presence and work in creation and history and special presence and work in the person and work of Jesus of Nazareth. The culmination of this line of reasoning is that the

dialogical nature of God was revealed especially in Jesus’s death and resurrection, where God’s love for the world was poured out fully and then shared abundantly with Jesus’s disciples as they are called to participate in God’s very mission through the pouring forth of God’s Spirit upon them (see the whole movement of Acts, and especially Acts 2). God’s saving and redemptive purposes in creation and history, accomplished in a creative prophetic dialogue, had been worked out in the history of Israel and in the ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Through the Spirit, the church became God’s agent, God’s partner even, in fulfilling God’s saving purpose. (14)

The agency or partnership of the church—the church’s action in mission—relates to God’s presence and action in the word “through the Spirit.” Furthermore, this relationship is predicated on the “nature of God” revealed in Jesus, which is Bevans’s unique spin on social Trinitarianism: “God not only practices prophetic dialogue in God’s saving presence and action in creation and history; God is in God’s very self a communion of prophetic dialogue. In baptism, Christians are plunged into this communion and are called to share God’s life of dialogue and prophecy within the created world and in human history” (14–15). Participation in God’s mission through the Spirit is, then, realized sacramentally. In turn, the church itself becomes sacramental—in the words of the Vatican II document Lumen Gentium, “the church is ‘like a sacrament or as a sign and instrument both of a very closely knit union with God and of the unity of the whole human race’ ” (15).

In the second chapter, Guder lays out his multicultural and translational approach. He begins by referring to “the broadly affirmed consensus on the missio Dei as the central and comprehensive definition of the church’s purpose and action” (22). Of course, the very existence of the book to which Guder is contributing brings the claim of consensus into sharp doubt. The fact is that despite the ubiquity of reference to missio Dei among a broad field of traditions (in part because of Guder’s own work), there is no single definition of God’s mission, much less a consensus on how such a definition would clarify the church’s mission. That is precisely the problem and the book’s raison d’etre! To say, as Guder does, that “this priority of God’s mission locates the church within God’s purposes and ongoing activity in human history, and it constitutes an implicit critique of approaches to the church and its mission that make the church an end in itself” (22) falls far short of specifying what those purposes and that ongoing activity are and just how the church might be located “within” them. I do not dispute the claim that many serious mission scholars share this “sense of theological priority” (22), but as consensus goes, it is threadbare.

Fortunately, what the reader is looking for instead of a claim to consensus is what Guder ultimately has to offer: his perspective on what it means to say the church’s mission is located within God’s mission. His answer is an essentially Barthian one: “Witness is the biblical concept that draws together all the strands of the church’s purpose and action” (22). The adjectives multicultural and translational modify Guder’s conception of witness, which he also glosses as contextualization: “the vastly complex process by which the witness of the called and sent community is formed for particular cultural contexts so that the witness mandate is faithfully carried out from one cultural setting to the next” (22). The critical point, however, is that the Barthian notion of witness serves to mark an absolute hiatus between the work of God and the witness of the church. God does the work—the church merely witnesses to it. Even the act of translation is the work of the Spirit: “it is the Spirit’s empowering work to enable the articulation of the gospel in every culture, as it is translated by faithful witnesses carrying out the apostolic mission” (23). This is as close as Guder comes to discussing the mission of the church in terms that might be called a thick account of divine-human cooperation. Thus, the reader will not find in Guder’s contribution the kinds of phrases to describe the work of the church that crop up in other chapters, such as “continuing Jesus’s mission in the world” (Bevans, 15), “extension of Jesus’s ministry” (Padilla DeBorst, 44), or “manifest and advance God’s kingdom on earth” (Stetzer, 92), much less the divine-human synergism of Orthodox theosis (Rommen, 79–80). All the church does is witness, with its concomitant acts of translation.

Furthermore, the emphasis in Guder’s perspective falls on the nature and identity of the church rather than its action—he would rather say that the church is missional than that the church does mission. Hence, he characterizes the multicultural and translational approach through a missional interpretation of the Nicene marks of the church—the adjectives one, holy, catholic, and apostolic. I leave the assessment of the particulars to the reader. The upshot, in any case, is that when apostolic refers to “the apostolic mission of making the gospel known through the formation of witnessing communities” (24) and catholic refers to the “multicultural character of the missional church” (25), then “the holiness of the church is reoriented toward the actual practice of empowered missional witness” (30). The phrase “actual practice of empowered witness” might give one hope that some specification of what the church does to witness will be forthcoming. But Guder continues:

The work of the Holy Spirit from Pentecost onwards has been to equip the human and often frail company of God’s people to carry out their vocation. Their holiness then consists of all that God’s Spirit does in, with, and through them to ensure that “grace that is reaching more and more people may cause thanksgiving to overflow to the glory of God” (2 Cor. 4:15). Just as the church is not an end in itself but the divinely called instrument of God’s saving mission, the spirituality of the Christian person and the Christian community is also not an end in itself. This equipping for holiness . . . serves both the apostolicity of the missional church and its practiced catholicity by drawing the church ever more deeply and comprehensively into the service of God’s healing mission. (30)

What does the service of God’s healing mission entail? Guder does not say. Even as the discussion of holiness turns to “the discipling of the ethnicities,” (31) the discussion oddly lacks a subject. Who does the discipling and what does the activity consist of? Guder responds, “In effect, the Gospels demonstrate what discipling actually consists of: learning Jesus by living with him, listening to him, imitating his actions, and memorizing his teaching” (32). Oddly, these are all the actions of the disciple, not the discipler, as though discipleship were a do-it-yourself process, confirming again Guder’s reticence to specify what one does in apostolic mission. Indeed, he suggests that “gospel witness works itself out” through “the formation of witnessing communities” (32). The formation of communities with missional characteristics results in witness working itself out. This is ultimately in keeping with Guder’s Barthian conception of witness, but I find it striking that the formation of the church is the real work in view here—an observation that perhaps explains why Guder is so emphatic that “the church is not an end in itself but the divinely called instrument” (30). It is easy to take the church for an end in itself when the most concrete missional action in view is the formation of the church.5 Guder’s prefered metaphor for the church “within” the mission of God—instrument—is indicative of the passivity that his perspective seems to assume.

For Guder, witness is a consequence of the church’s existence as the church, and the church’s existence is missional because witness is its consequence. The only question is whether the witness of the missional church is contextualized. The multicultural and translational approach to mission entails the contextualization of the local church’s witness; the mission of the church is to be formed contextually.

In the third chapter, Padilla DeBorst advocates an integral transformation approach. Of the perspectives represented in the two volumes reviewed here, Padilla DeBorst’s is both the only female voice and the only Majority World voice. Some readers may also find it noteworthy that both Padilla DeBorst and Stetzer identify as Evangelicals. Whereas Bevans, Guder, and Rommen each represent distinct, major Christian traditions, Ott features two Evangelical alternatives. Giving integral transformation its own place correctly signals the approach’s distinctiveness, however. I will return to the contrast between Padilla Deborst’s and Stetzer’s perspectives once I have discussed both.

The chapter does a nice job of surveying the historical context of the approach’s development within the Evangelical mainstream, particularly among Latin American missiologists. The integral transformation approach challenges the “Western, dualist, socially unengaged, and otherworldly looking Christianity” (50) that twentieth-century Evangelical missions in particular promulgated. It is, above all, a holistic approach to mission, not given to the excesses of either Evangelical conversionist church planting or Latin American liberation theology. Somewhere between these two major influences, participation in God’s mission “has to do with the transformation of human life in all its dimensions, not only the individual or sacred, but also the social and secular” (52).

Theologically, Padilla DeBorst contends that her approach’s “grounding is trinitarian, having to do with God’s kingdom, Jesus’s life and ministry, and the ever-present work of the Spirit” (44). Thus, “mission lived as an extension of Jesus’s ministry” (44) has a trinitarian structure: “mission is carried out by all the people of God who recognize they are empowered by the Holy Spirit to follow Jesus in living into the kingdom of God in their everyday lives” (61). “Prophetic embodiment of the gospel” (58) is the phrase that perhaps best captures this vision of imitating Jesus’s participation in God’s mission, by the power of the Spirit, by “being, doing, and saying” (44) expressions of God’s reign. The integral transformation approach puts flesh on the bones of Guder’s contextualized witness, insisting that “through the work of the Spirit, the church is called to prophetically embody the good news today” (59).

Ultimately, God’s mission is “integral redemption: that all people may enjoy the life in abundance that God intends through Jesus Christ and the power of the Holy Spirit” (52). To say, then, that “the vocation of the church in history is derived from God’s mission (missio Dei)” is to say that the church’s mission is to be, do, and say what “carries out” that integral transformation—by the power of the Holy Spirit. In my analysis, this is a usefully practical expression of what the church does in mission. Furthermore, it is appropriately qualified by a trinitarian framing. Nonetheless, the burden of the trinitarian qualification falls on the church’s imitation of Jesus, so it is not evident how a truly trinitarian theology animates the integral transformation account of the church’s mission. How is the ongoing missio Dei conceived, and how does the church’s being, doing, and saying relate? Bevans’s attention to God’s triune life and the church’s union with God is an illuminating contrast.

In the fourth chapter, Edward Rommen lays out a sacramental vision approach from the Eastern Orthodox perspective. Appropriately named, sacrament—especially the Eucharist—is at the heart of this perspective, but it is a vision of sacrament rooted in an understanding of salvation as theosis—“becoming increasingly and finally completely like God in his personhood and character” (71). “We understand the primary task of mission,” says Rommen, “to be personally introducing Christ to those who do not yet know him so that they, through faith, can enter into communion with him and begin the journey to salvation” (69). In short, communion leads to salvation, so the mission of the church is to be the place where communion is made possible.

Mission is profoundly church-centered from this perspective, in the sense that the sacraments are administered in the assembly of the church. Although church members are “dismissed into the world as witness of what they have seen,” the invitation to “come and see” is the essential paradigm of mission (77). Positively, the sacramental vision approach prioritizes relationship over information in evangelism: “Whatever else it might be, the mission of the church involves the facilitation of a personal encounter with the Lord of life, Jesus Christ” (78). This sacramental encounter, however, can only happen in the context of the church’s authorized celebration of the Eucharist. There is a significant tension here: on the one hand, those to whom the presence of Christ is mediated through the Eucharist can “extend the liturgy into the non-ecclesial or pre-ecclesial world around them,” but on the other hand, the real saving encounter with Jesus only takes place “in the eucharistic assembly” (81).

The upshot of this construal is that church planting is extremely important, but only those with the apostolic authority to administer the Eucharist can plant legitimate churches. That is, “ecclesial authority or legitimacy” (87) is a matter of apostolic succession. This stricture seems to be what typically causes Protestant missiology to screen out Eastern Orthodoxy more even than it does Catholicism. The concern for both apostolic legitimacy and sacramental encounter—Rommen usefully coins the phrase “ecclesio-sacramental integrity” (84)—certainly characterizes the sacramental vision’s unique approach to mission.

Yet, the chapter’s more interesting distinctive, in my view, is the place of theosis. It constitutes a major addition to the book for two reasons. First, Rommen’s discussion of theosis relies more substantively on a trinitarian theology than any other perspective. Here, the social trinitarianism of John Zizioulas plays a major role. Regardless of the conflict between classical and social views of the Trinity (fueled in part by Zizioulas’s work), Rommen foregrounds the potential of trinitarian theology for fleshing out one’s view of the church’s mission.

Second, the chapter reveals how the sacramental vision puts limits on the missional implications of theosis.6 For Rommen, theosis is an understanding of the consequence of mission (i.e., salvation), not an understanding of mission itself. Rommen explains the distinction with reference to the Eucharist. If sacrament is not rightly administered, “the special manifestation of Christ is not present” (84), without which theosis is not sustained. The special presence—Christ himself available in the Eucharist—that nourishes theosis is, in other words, precisely what is lacking outside the context of ecclesio-sacramental integrity. In contrast, the theology of missio Dei typically conceives of mission as, in some way, attending to the saving presence of God in the world beyond the church assembly. Thus, the presence/absence binary in the sacramental vision approach marks the key difference between theosis as salvation and theosis as mission. Rommen almost finds a mediating position in his discussion of the maturity (i.e., progress in theosis) necessary to “introduce Christ to someone else”:

It is only the mature believer who is in a position to initiate communion in a field of human-human presence by being fully present to others. The very act of inviting becomes a form of humble service, an unmistakable expression of love, given and received in complete freedom. It includes the ability to challenge another person’s beliefs while at the same time showing oneself to be a servant; the ability to direct attention to Christ’s presence in the witness’s own life without focusing on the self; and the ability to call the other to an abandonment of self-love while demonstrating a self-emptying love of other. (86)

The presence of the witness allows the witness to direct the other’s attention to Christ’s presence in the witness’s life. This comes close to a claim that Christ is present in the missional encounter with the other, but inviting-to-assembly is still the operative paradigm. How could it be otherwise, when the presence of Christ in the witness’s life is only derivative of Christ’s special Eucharistic presence? The implications of theosis as union with Christ still need to be worked out missiologically, and the inclusion of the sacramental vision approach greatly enlivens that possibility.

In the fifth chapter, Ed Stetzer articulates the evangelical kingdom community approach. Stetzer, the Executive Director of the Billy Graham Center for Evangelism at Wheaton College, undoubtedly represents the American mainstream Evangelical understanding of the church’s mission: “God’s people are to participate in the divine mission to manifest and advance God’s kingdom on earth through the means of sharing and showing the gospel of God’s kingdom in Jesus Christ” (92). The crux of this definition is its notion of the divine mission: manifestation and advancement of the kingdom. Thus, although Stetzer begins with the same ecumenical missio Dei concept from which Guder works, God’s mission is essentially an objective task, not a trinitarian reality. Notwithstanding Stetzer’s assertion that “sending is part of [God’s] very nature,” his emphasis falls squarely on the idea that “God has a mission”—a “purpose,” “agenda,” and “plan” (97–99). This to-do is what the church undertakes when it participates in God’s mission.

The accent falls, therefore, on the agency of the church. Indeed, this is an intentional, corrective move: “While evangelicals have been helped by recognizing that, by and large, mission belongs to God, they have not forgotten that God calls the church to be the primary agent in his mission” (92). There is a pneumatology at work that softens this claim: “The church is born as a result of the Spirit’s mission, and the Spirit empowers the church for its mission as it participates in God’s mission” (105). Nonetheless, “God’s mission is to advance his kingdom” (100), and “Scripture bears witness that God advances his kingdom in this age through the lives of people” (103). The role of the church as the primary agent of the kingdom is the key distinctive of Stetzer’s perspective.

How, then, does the church know it is fulfilling God’s purpose? As with Padilla DeBorst’s approach, imitation is key. Stetzer characterizes imitation as “joining in Jesus’s mission,” which includes saving and serving. Saving refers to personal evangelism and church planting. Serving refers to works of justice and acts of mercy. While this might look like the holism that Padilla Deborst wants, the approach aims to correct the tendency of ecumenical missio Dei theology to be overpowered by modernist ideologies (capitalism, Marxism, etc.), to which Stetzer adds “the social gospel, liberation theology, and solidarity with the poor.” He adds, “These movements all but supplanted mission with social action by defining kingdom—and how kingdom is bigger than the church—primarily as societal transformation” (106). His warning demonstrates the extent to which mainstream Evangelicalism, in contrast to that represented by Padilla DeBorst, is still reacting to the perceived threats of theological liberalism, even to the extent that Stetzer would identify “solidarity with the poor” as a movement that supplants mission.

Assuming my trinitarian-practical criterion, the obvious strength of Stetzer’s perspective is its ability to satisfy the practical dimension. By objectifying mission as God’s agenda, the evangelical kingdom community understanding of mission has no problem specifying what the church does in mission. Unfortunately, by the same token, it obscures God’s triune agency and reduces participation in God’s mission to “advancing the kingdom,” however Evangelicals might define that work. A useful contrast arises from setting the evangelical kingdom community approach alongside the others in this volume: the church’s agency may be conceptualized in relation to God’s purpose or in relation to God’s being. Focusing on the former tends to obscure God’s own agency. A stronger focus on God’s being tends to foreground God’s agency and thereby problematizes the church’s mission in the way that missio Dei theology should—particularly for those traditions that have frequently engaged in a kind of kingdom building that retrospectively looks like imperialism. Stetzer, who is aware of this tendency, ends the chapter by appealing to Newbigin’s “sign and instrument” language. It is not clear to me that the passivity of this rhetoric does justice to the strong agency the rest of the chapter portrays or that it is sufficient to counterbalance the reality of Evangelical missions that the chapter accurately represents.

The brief response chapters that follow extend the discussion in inconsistently useful ways. Some of the responses are a masterclass in ecumenical dialogue, demonstrating both graciousness and critical engagement. At the same time, there is a significant amount of reiteration. At other points, the authors make productive additions. Bevans, for example, goes into further discussion of the Trinity. Padilla DeBorst makes more of the uniqueness of her perspective as a Latina. And Stetzer makes clearer that, in his view, holism does indeed lead to the neglect of evangelism. Overall, I was satisfied with both the quality and selection of the approaches in The Mission of the Church. There were, however, some gaps in the discussion that the next book helps fill.

Four Views on the Church’s Mission

Typical of a volume in Zondervan’s Counterpoints Series, the scope of Four Views on the Church’s Mission is narrower than the preceding work. Sexton calls it “an intra-evangelical conversation seeking to bring mission and church more closely together” (12). Hence, the book bears out the observation—already signaled by the two Evangelical authors and the Evangelical editor of the former work—that the debate about mission is nowhere livelier and more diverse than among Evangelicals. Perhaps surprisingly, the Evangelical approaches in Four Views map onto the gamut of approaches already discussed. Rather than overloading the Evangelical corner of the table with nuance, Sexton hosts a conversation that demonstrates how Evangelicals fall along the entire spectrum and fill it out.

Sexton’s introduction specifies the major problematic dimensions of Evangelical missions (corporatism and colonialism), identifies the main theological problem (the gap between the being of the church and the doing of mission), and summarizes the key to the whole discussion (“whether mission is an expansive thing or a reduced thing” [13]). The four views are respectively labeled “soteriological mission” (Leeman), “participatory mission” (Wright), “contextual mission” (Franke), and “sacramental mission” (Leithart). Each contribution is followed by short responses by the other three authors.

In the first chapter, Leeman represents the soteriological mission view that contends “the threat of God’s eternal wrath is the most urgent matter of all” (30). It is “probably fair to label me the book’s fundamentalist,” he says, though the chapter is full of finesse. Leeman parses “narrow mission” and “broad mission,” making a place for both. “In a phrase, the broad mission is to be disciples or citizens, and the narrow mission is to make disciples or citizens” (20). He characterizes this distinction as two separate biblical storylines, the kingly and the priestly. “The kingly story suggests that the church possesses a broad mission: to image God in everything; to live as just and righteous dominion-enjoying sons of the king” (26). Here there is room for justice and mercy in mission. In the priestly story, “God has authorized churches to mediate his judgments in the declaration of salvation and in the separation of a people unto himself in spite of all their sins and rebellion. Narrowly speaking, then, the mission of the church, in some sense of that word, is to make disciples by declaring or mediating God’s judgments, which it does through gospel proclamation, baptism and the Lord’s Supper, and instruction” (29). Narrow mission, therefore, is evangelism and church work.

It is a relief to see such nuance, but ultimately Leeman’s is an exercise in prioritization. The issue is urgency: “At this moment of redemptive history, what does humanity most urgently need to be saved from?” (21). The point is that “our answer will impact what we think the church is sent to do” (22), and the holistic answer is wrong. The need to be saved “physically, politically, economically, and socially” is not as urgent as the need to be saved from God’s wrath. Leeman gives this prioritization an eschatological explanation: “the local church was uniquely designed and established for this stage of redemptive history to do ‘elevator work,’ ” which entails lifting kingly callings (vocational image-bearing) from the old-creation timeline that ends with the second coming of Christ to the new-creation timeline that continues into eternity. Regenerate kingly callings thus become broad mission through the “elevator work” of priestly narrow mission. In other words, there can be no broad mission without narrow mission first; the church must make disciples if anyone is to be disciples.

In order to see what Leeman is doing, it is vital to understand the implications of his eschatological model. Unregenerate kingly callings cease with the second coming—and with them, logically, the suffering and injustice caused by human sin. God will deal with those problems when the time comes. In the meantime—in this stage of redemptive history—the church’s priority is to get people on the elevator and up to the regenerate life that continues beyond the second coming. Hence, “the church’s goal is not to transform the world but to live together as a transformed world, and to invite the nations in word and deed to the Transformer” (43). This scheme makes me think that when Leeman complains about the “holistic camp” creating a strawman of a disembodied view of the afterlife (23), he protests too much. The issue for missional holists is not whether dualists believe in bodily resurrection but whether their eschatology makes priestly “elevator” ministry essentially an exercise in escapism.

Evaluating the practical dimension, the soteriological view delineates quite specifically what the church is to do in mission—in fact, that is its sole concern. It is, however, theologically blinkered. The triune mission simply is not in view, and this results in an inability to see how the church might participate in God’s ongoing redemptive and transformative work in the world. I commend Leeman’s more balanced approach to matters of justice and mercy and his understanding of discipleship as, in some sense, mission. These strengths point toward a deeper and wider vision of the church’s participation in God’s mission. And, given the sheer number of Evangelicals who engage the church’s mission on the terms Leeman articulates, our array of perspectives on the church’s mission would have been badly incomplete without this chapter.

In the second chapter, Wright’s participatory mission view condenses his influential characterization of the church’s mission through a narrative biblical theology. He explains: “If we are to understand the mission of the church, then, we must understand the overarching biblical narrative within which the church participates as, on the one hand, the people of God in the present era between the first and second coming of Christ and, on the other hand, the people of God in spiritual and theological continuity with Old Testament Israel: in short, as those in Christ and thereby also in Abraham” (65). To this end, Wright deploys a narrative hermeneutical strategy that has become well-known and widely accepted among Evangelicals—the portrayal of the biblical stories as a drama that unfolds in discrete acts. By foregrounding the theme of mission in each act, he develops “a fully biblical understanding of the mission of God’s people” (73). In the current act, therefore, the church is “to live within the Bible’s own story and participate in its great unfolding drama. Mission is not merely a matter of obeying God’s commands (such as, for example, the Great Commission—vitally important as that is), but of knowing the story we are in and living accordingly, bearing witness to the mighty acts of God (past and future)” (77). This insistence on a thick biblical account of mission has been a major missing element to this point.

Furthermore, as the lead architect of the Cape Town Commitment (the major document that emerged from the Third Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization), Wright’s perspective significantly supplements Padilla DeBorst’s and Stetzer’s. Both place a great deal of the burden of discerning the practical meaning of participating in God’s mission on imitation of Jesus’s life and ministry. Wright broadens the basis of this discernment considerably, in that “how we are to live, and what we are mandated to do as God’s people in the world, are constantly rooted in the facts of who God is and what God has done” (65–66)—meaning, the whole story of God’s being and doing revealed in the biblical narrative (although, a major critique of Wright is that he starts with Abraham rather than reading from Gen 1 forward). This broadening also entails an unequivocal evangelical holism in common with Padilla DeBorst and in contrast with Stetzer (and, of course, Leeman). Wright distills “a truly holistic and integrated understanding of mission” into three domains:

- Cultivating the church through evangelism and teaching, colaboring with Christ to see people brought to repentance, faith, and maturity as disciples of Jesus Christ.

- Engaging society through compassion and justice, in response to Jesus’s commands and example, to love and serve, to be salt and light, to be “doers of good.”

- Caring for creation through the godly use of the resources of creation in economic work along with ecological concern and action. (81)

The strength of Wright’s corrective to dualism is that it is based neither on proof-texting nor on ideological imposition but on a carefully, openly argued interpretation of the trajectory of the whole Bible.

The problem that Wright’s approach presents is that participation in God’s mission is clearly participation in the drama, not participation in the triune missio. Therefore, Wright sees participation in mission as essentially a function of the church’s identity as God’s people by virtue of their place in the narrative: “God has called into existence a people, in the midst of all the nations of the earth, to participate with God in his purposes for the world—‘coworkers with God,’ as Paul put it. This does not mean that we do everything God does. God is God, we are not. But it does mean that our understanding and practice of mission must reflect in some way, however imperfectly and provisionally, the comprehensiveness of God’s biblically revealed actions, concerns, commands, promises, and intentions” (90). In this view, being coworkers with God proceeds on a distinction between what God does and what the church does rather than a notion of participation in that divine action. The phrase “reflect in some way” is key. The church’s mission is some sort of reflection of God’s mission. Wright’s vision of God’s being and doing is big and rich because it is robustly biblical, but the concept of the church’s participation in God’s mission is, once again, reductively imitative. A more trinitarian approach is needed to push beyond this limitation. In my view, however, Wright has advanced the conversation by clarifying the problem: we need a narrative biblical approach to a trinitarian account of participation in God’s mission or a trinitarian interpretation of a narrative biblical account of participation in God’s mission—or both at once.

In the third chapter, Franke offers a contextual mission perspective in many ways continuous with that of Guder, his colleague in the Gospel and Our Culture Network. Franke’s focus is also contextual witness, though in a less Barthian key. Newbigin’s voice echoes loudest, culminating in Franke’s explanation of what it means that the church “is sent into the world by the triune God for the purpose of bearing witness to the gospel as a sign, instrument, and foretaste of the kingdom of God” (118). Appropriate to Newbigin’s legacy, this chapter is attuned to the cultural and sociological (hence contextual) dimensions of participation in God’s mission but also to the trinitarian dimensions. Indeed, of all the authors reviewed in this essay, Franke goes the farthest toward identifying and confronting the theological dilemma head-on: the problem with the “consensus” on the missio Dei “is that, while it served to inseparably link the mission of the church with participation in the mission of God, it did not lead to specification with regard to the precise nature of the church’s participation in that mission” (108).

Furthermore, he develops the problem by reference to contextual complications:

In keeping with the pattern of this sending, the mission of the church is intimately connected with the mission of God in the sending of Jesus and the Spirit. The church is called to be the image of God, the body of Christ, and the dwelling place of the Spirit in the world as it represents and extends the good news of God’s love for the world as a sign, instrument, and foretaste of the kingdom of God. However, given the local and particular nature of the church in its various manifestations throughout history, culture, time, place, the expression of this mission is always contextual and situated in keeping with the commission to bear witness to the ends of earth. (112)

Thus, when Franke says the mission of God is, in short, “love and salvation,” he is suggesting that “the salvific mission is rooted in the self-giving, self-sacrificing love of God expressed in the eternal Trinitarian fellowship and made known in the created order through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ” (114). To participate in love and salvation is to participate in the trinitarian fellowship—the missio Dei—further expressed in the world through the sending of the church. Franke therefore develops the metaphors of sign, instrument, and foretaste in terms of the image of God, the body of Christ, and the dwelling place of the Spirit, which is to say, as christological and pneumatological conceptualizations of participation in the triune life. In regard to the image of God, Franke is attentive to the New Testament notion of being “in Christ,” which he discusses in connection with “following the pattern of Jesus” (119–21). As the body of Christ, “the church is sent into the world and called to continue the mission of Jesus in the power of the Spirit” (121), which is particularly “to participate in the temporal, here-and-now activity of liberation” (123). And as for being the dwelling place of the Spirit, Franke highlights the eschatological peace that characterizes the community of the Spirit and its worship. Though all of these could be developed further biblically and theologically, Franke points to the potential of such development for clarifying in trinitarian terms just what participation in God’s mission might be and how attempting to do so without reference to context is futile.

Frustratingly, the primary weakness of Franke’s approach is precisely its ambiguity about what contextualization is. “All are called,” concludes Franke, “to do their part in the mission of God in accordance with the particular social and historical circumstances in which they are situated and the gifting of the Spirit” (133). It is disappointing that none of the authors in The Mission of the Church represent the tremendous missiological resources that have developed out of the imperative to contextualize mission work. It is almost bizzare that the one author in Four Views on the Church’s Mission who makes much of context also ignores those resources.7 This is a significant failure to meet the practical dimension of my criterion.

In chapter four, Leithart’s sacramental mission perspective casts the church’s mission in sacramental terms. A major premise of this argument is that discussions of mission routinely ignore the importance of the sacraments for mission. Footnote 10, which begins, “Not all writers on mission neglect the sacraments” (156), goes on to undermine this premise to a great extent. Nonetheless, Leithart’s viewpoint is a valuable, if peculiar, contribution to the overall discussion.

Humanity’s problem as Leithart reads the biblical story is that, after Adam and Eve were exiled from the Garden of Eden, “human beings no longer had access to the presence of God” so that although they continued to rule, “they no longer ruled as the companions of their Creator” (159). “That is the setting in which God set out on his mission to restore humanity, and his goal was to restore humanity to fellowship that would produce godly dominion” (160). Like Wright, then, Leithart takes the biblical story to construe “mission” as the goal of God. In this scheme, he casts Abrahamic “flesh-cutting [i.e., circumcision] and altar-building [i.e., sacrifice]” (162) and the Mosaic “rhythm of life and liturgy” (163) as sacramental—having to do with drawing near to the presence of God. Following the ministries of John the Baptist and Jesus, the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper both proclaim and effect the restoration of humanity. Moreover, the baptized “who feast on the body and blood of Jesus are empowered by the Spirit as witnesses” (164). The conclusion toward which this construal drives is that “purification and meal, baptism and the Supper, have been centerpieces of the mission of God and the life of the people of God since the beginning. . . . God’s mission is to restore the original harmony of liturgy and life, and . . . this intention comes to a focus in the Christian sacraments” (165).

There are strong connections between Leithart’s Protestant sacramental mission approach and Rommen’s Orthodox sacramental vision approach. Indeed, Leithart provides another important pathway to an understanding of theosis in relation to mission. Both sacraments entail “union with Christ” and “participation in Christ” in theologically profound ways (166–67).

Leithart’s contribution also pushes the discussion toward an overtly political theology that has been largely lacking in the discussion so far. In his view, the reunion of humankind in Christ is at the heart of the church’s mission: “she is sent to the world to disciple all people groups by baptizing them, teaching them the commandments of Jesus, and welcoming them to the table of the Lord. In this, the church is God’s instrument to fulfill his mission to reunite the human race” (168). But this unity is of overtly political significance; it constitutes a political body: “Unity is a goal of the mission of the church. We proclaim the gospel to gather people from every tribe and nation into one new humanity that is the church. But pursuit is also a dimension of the political activity of mission. By maintaining unity or reestablishing broken fellowship, the church comes to visibility as the contrast society, as a unified humanity in a world of fragmentation and coerced unity” (174). In my view, missional ecclesiology literature encompasses two prominent political bents, the separatist and the activist. Leithart’s notion of a contrast society leans toward the separatist. This balances his earlier conception of the basic human problem in terms of dominion, though in the end he discusses political leaders discipled by the church, as well as a broad cultural mission, all of which leans toward the activist bent. A complete discussion of the church’s mission would be better served by a strongly activist viewpoint and a strongly separatist viewpoint, but Leithart at least raises the issue.

Sexton offers a brief concluding chapter that recasts the discussion retrospectively in terms of “being and acting.” The limited viewpoints of four Anglophile males with British PhDs, as well as the authors’ ecclesial traditions, come into view momentarily. The primary concern, however, is how the question “What is church?” relates to what the church does in mission. Sexton points toward the issue but offers little in response. I will pass over the response sections of each chapter in order to offer a concluding synopsis. However, I note that although no author makes a major shift in response to another, the discussion is not inconsequential, and the multiple responses makes for a livelier discussion than the format of The Mission of the Church manages to generate.

A Synoptic View of the Nine Perspectives

A side-by-side comparison of such a diverse set of perspectives is difficult for a number of reasons. The most difficult problem is that any comparison is dealing in limited, subjective representations rather than proportionate scales of difference. Nonetheless, I offer below a taxonomy of the approaches as one (admittedly impressionistic) way to advance the conversation these books have curated. Limited as these viewpoints are to primarily white, Western males, another difficulty is that there is no way to compare for socio-cultural variables. How do the diverse perspectives (minority, feminist, majority-world, etc.) that have become so important for contemporary theological method conceive of the church’s mission? Here I can only note the problem. A third difficulty is that each perspective brings some unique contribution to the table, which can only be evaluated in comparison with other perspectives in terms of its absence. For example, the sacramental perspectives make a sort of absolute addition to a discussion that otherwise ignores the sacraments, but it is not particularly useful for evaluating other positions that may simply take for granted the importance of the sacraments for the formation of the missional church (as is likely the case for Bevans, a Roman Catholic). More pointedly, the perspectives that attend to contextualization make a major missiological contribution, which one might consider especially relevant for defining the mission of the church. Still, others might take contextualization to be a matter of method rather than theological substance or just an inevitable process; this makes it hard to determine whether one is more contextual than another. I will limit my taxonomy, therefore, to only two dimensions, in keeping with the criterion I layed out initially: the theological and the practical.

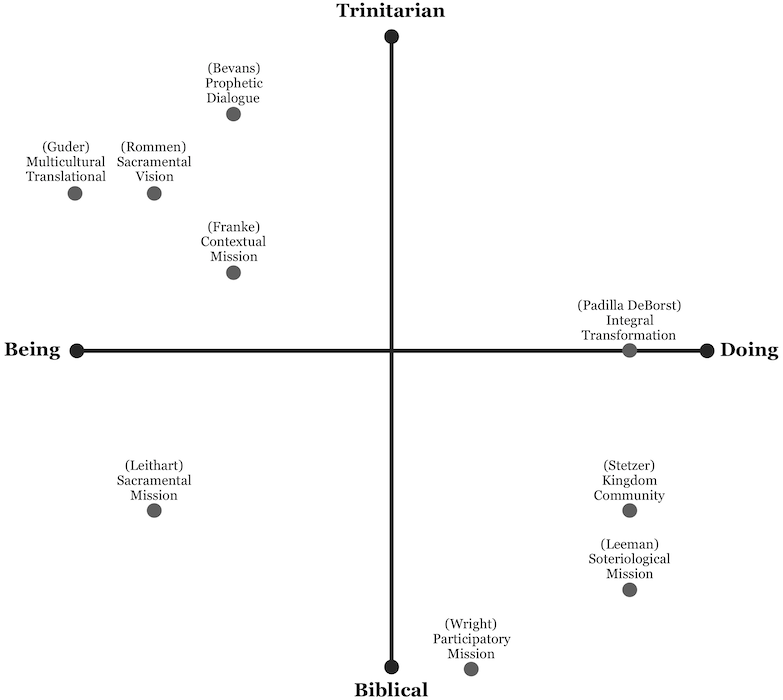

Instead of reducing these dimensions to binaries (theological/not-theological or practical/not-practical), I want to construe them as dialectic axes whose poles are equally good. The poles of the theological axis are Trinitarian–biblical, and the poles of the practical axis are being–doing, represented as follows:

Figure 1: Plotting Perspectives on the Church’s Mission

The purpose of organizing these dialectics visually in this way is, principally, to represent the desired bullseye. A perspective with an equal focus on a trinitarian and a biblical understanding of the missio Dei and an equal focus on the practical aspects of being a missional church and acting in mission would be plotted dead-center, at the intersection of the two axes. The point is not that if one is less trinitarian, then one is more biblical (by no means!), or that if one is more concerned with the being of the church, then one is less concerned with the action of the church. To be as extremely trinitarian and extremely biblical as possible would still put one at the center of the axis. These dialectics are tensive, however, which means that the common tendency is to let one pole overpower the other. I believe this is born out in the chapters I have reviewed, and in the theology of mission generally, but here I can only make the assertion. Again, my plotting of the nine perspectives is hardly objective, but I have read each chapter for the purpose of locating it fairly. While landing at the center of the graph is conceptually ideal, emphasizing any of the poles is good, therefore I intend this exercise to be descriptive far more than critical.

Assuming my plotting is in the ballpark, a few tendencies are evident. Some tend to emphasize a trinitarian/being view of the church’s mission, and some tend to emphasize a biblical/doing view of the church’s mission. Leithart is an oddity in that he emphasizes the being of the church through a strongly biblical approach to the sacraments but is minimally trinitarian in his construal of mission. Generally, the biblical/doing view tends to be more recognizably Evangelical. None, in my reading, do a great job of holding both dialectics in strong tension. No one emphasizes a trinitarian/doing view of mission, which is evidently another expression of the established problem: it is exceedingly difficult to conceptualize mission in a way that makes much of both the actio Dei and the actio ecclesiae. Again, though, landing in the trinitarian/action quadrant is no better than landing in any other. The nexus of the two axes is the ideal tension, in my view, because the biblical and being poles are also important. In this sense, one can see how Leithart is doing overtly corrective work—just not the kind that addresses the question I have prioritized throughout the review.

Certainly, had the authors been aware of the scheme into which I have fitted their perspectives, they might have highlighted other aspects of their understandings. My graphic synopsis is little more than a heuristic device. The really valuable work is that of the authors. If nothing else, it should be all the more evident why reading them together is the best way toward a well-rounded or properly tensive understanding of the church’s mission. We can be thankful for the many perspectives available to the church as we strive to participate in God’s mission.

Greg McKinzie is a PhD candidate at Fuller Theological Seminary and the executive editor of Missio Dei. From 2008 to 2015, he served in Arequipa, Peru, as a partner in holistic evangelism with Team Arequipa (http://teamarequipa.net) and The Christian Urban Development Association (http://cudaperu.org). Greg holds an MDiv from Harding School of Theology and an MA in missions from Harding University.

1 Craig Ott, ed., The Mission of the Church: Five Views in Conversation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016).

2 Jason S. Sexton, ed., Four Views on the Church’s Mission, Counterpoints Bible and Theology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017).

3 This distinction has been a part of the contemporary discussion since Karl Hartenstein first introduced missio Dei terminology in his interpretation of the 1952 Willingen document “A Statement on the Missionary Calling of the Church.” He says, “In a second section, the missionary obligation of the church is comprehensively established. The mission is not a matter of human activity or organization; ‘its source is the Triune God Himself.’ The sending of the Son for the reconciliation of the universe through the power of the Spirit is the cause and purpose of mission. From the ‘missio Dei’ alone comes the ‘missio ecclesiae.’ Thus, the mission is placed in the widest possible framework of salvation history and God’s plan of salvation.” Karl Hartenstein, “Theologische Besinnung,” in Mission zwischen Gestern und Morgen, ed. Walter Freytag (Stuttgart: Evangelischer Missionsverlag, 1952), 62; my translation.

4 Douglas McDermid, “Pragmatism,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: A Peer-Reviewed Academic Resource, https://iep.utm.edu/pragmati.

5 This reading is confirmed by the list of nine “trajectories” in the final section of the chapter, all of which are practices internal to the church. I do not doubt that Guder would approve of concrete actions in “the service of God’s healing mission,” but in terms of analyzing the chapter and its implications alongside other construals of the church’s mission, it is evident that not specifying such actions is a dimension of his answer to the question Ott has framed.

6 In particular, this provides an informative contrast with Michael Gorman’s recent appropriation of theosis in relation to the missio Dei in Becoming the Gospel: Paul, Participation, and Mission, The Gospel and Our Culture Series (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015).

7 See A. Scott Moreau, Contextualization in World Missions: Mapping and Assessing Evangelical Models (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2012), for a recent overview.