Drawing on qualitative interviews with the Makua-Metto people of Mozambique, the author develops a curriculum addressing the topic of poverty. The contextualized approach considers poverty as a system and makes use of local solutions. The article includes a diagram illustrating the causes of poverty and two series of narratives linked by the metaphor of games to demonstrate Makua-Metto behavioral norms of people in poverty and those living free from its deepest effects.

The father smiled as his son leaned forward to listen. These two men live in a remote village in Mozambique, and during a single growing season they will produce all the corn, cassava, and beans that their family will consume for the rest of the year. The son is a motivated young man who makes money by cutting and selling wood. Both of the men are followers of Jesus, but while the father has been engaged with the church from the beginning, this is one of the first times I’ve seen the son really perk up and show interest in the topics we have been addressing among their small cluster of churches. Today, as we sit in the shade on my porch, we’re talking about poverty: what it is and the practicalities of overcoming it. And today, this young man is really paying attention.

When our mission team first moved to Mozambique in 2003, it was one of the poorest countries in the world. And although in recent years our host country has begun to climb up the development scale, the vast majority of our friends still live in abject or absolute poverty. In 2014, Mozambique ranked number 178 out of 187 in the UN’s Human Development Index (Haiti and Afghanistan rank ten and nine spots higher, respectively). Over seventy percent of the population lives in “multidimensional poverty,” and over eighty percent lives on less than two dollars a day. Statistics like these are both mind-boggling and misleading because the situation in Cabo Delgado, the province where the Makua-Metto people are most concentrated, is even worse. They live far from the economic advancement concentrated in the country’s capital, and the rare person here with a job earning more than two dollars a day supports his or her immediate family and many extended relatives.

In an attempt to begin understanding what it means to respond effectively to poverty in this region, I searched for helpful resources. Unfortunately, it seemed that most books on poverty in the developing world fall into one of two categories. There are the books that attempt to help rich Westerners understand poverty. And then there are books that advocate a specific strategy, often giving the impression that their single solution is the silver bullet. Our mission team has attempted a handful of initiatives with varying degrees of success, but I now believe that in our attempts to address absolute poverty meaningfully in this context one of the most important things we do is present it as a system whose complex solutions must involve the Makua-Metto people’s own cultural understandings.

After doing qualitative interviews about poverty with Makua-Metto people (both Muslim and Christian) and triangulation of the data in small groups, I found that even though their dominant cultural pattern is defined by absolute poverty, there are a subset of practices and perspectives that, if adopted by a wider group, could bring real, lasting change. I presented my findings mostly in rural church clusters but also in a variety of settings, from a high school debate club to a women’s business seminar, and I found that four pieces of the material on poverty among the Makua-Metto people were particularly appreciated and warrant sharing with a broader audience. My hope is that this article will provide people working with the poor in different contexts with ideas for helping those they serve to find effective ways to escape the pull of poverty.

The first half of this article considers Old Testament texts that resonate with our predominantly Muslim setting in northern Mozambique, while the second half illustrates an approach to poverty as a system and concentrates on using local solutions. In the beginning section, we look at how the book of Genesis can orient this discussion of poverty. My belief that God’s word has something meaningful to say about this topic comes from a conviction that the Creator is ultimately displeased when his creatures live in absolute poverty. In the second part, we look at formative biblical texts for Israel as a community that are essential in teaching about poverty in northern Mozambique because they encourage participants to move beyond a motivation of mere wealth accumulation and see poverty alleviation as a way of living in line with God’s desire for a whole community. In the third section, I offer a diagram that illustrates the factors and causes of poverty and wealth as part of the same system. The final part, and the material on poverty that most resonated with Makua-Metto participants, uses the metaphor of contrasting games and a narrative structure to show how the rules of absolute poverty play out in daily life in this context and contrast them with real patterns of life exhibited by those free from the system of absolute poverty.

Starting at the Beginning: The Book of Genesis and Defining Poverty in Text and Context

In conversations about absolute poverty with our Makua-Metto friends, it was important to begin by defining terms. The Hebrew Scriptures have a rich vocabulary for describing the poor and their situation. There are “between five and seven Hebrew root words from which derive terms that occur more than 200 times in the Bible to describe the poor and poverty.” Recognizing the extensiveness and variety of poverty language in the biblical text as well as in their own everyday speech was encouraging to Makua-Metto participants as they saw its relevance in both contexts. This process of defining relevant words in their language always provokes spirited conversation as they distinguish between ohuva (general term for suffering), masikini (term used to describe disabled or physically handicapped people), ntiriki (derogatory term for a fool or mentally deficient person), and atthu oveveya or wolwa (two terms that refer to laziness). Encouraging each group to name and define these keywords helped participants feel ownership of the process and recognize how the ways they already speak about absolute poverty provide clues for revealing its causes and effects.

During these discussions there has been quick agreement with the following statement:

Poverty is one of humanity’s biggest problems. It is often a result of social corruption, war, physical or economic disaster, or personal irresponsibility. Its underlying cause is sin, usually committed against those affected by it, and not by themselves. It is a painful, fearful, hopeless, and vulnerable way of life due to exploitation, isolation, lack of choice, and powerlessness.

Naming the direct and indirect connections between poverty and sin fits well within the Makua-Metto worldview. In order to begin thinking well about the gigantic challenge of poverty and humanity’s place in this world, it is helpful to point back to the beginning and revisit God’s intentions for creation over against the damaging consequences of sin. In that story, we learn (at least) three things relevant to a study of poverty.

First, the creation account defines our role. Genesis 1:27–31 shows God empowering and entrusting the first humans to work as stewards, beings who would prosper and multiply as they care for the earth. As Douglas John Hall notes:

The role of Steward is an honored one. In the literature of the Old Testament, the Steward is a servant but not an ordinary servant who simply takes orders and does the bidding of others. . . . He is a rather superior servant, a sort of supervisor or foreman who must make decisions, give orders and take charge. . . . The Steward is one who has been given the responsibility of management and service of something belonging to another, and his office presupposes a particular kind of trust on the part of the owner or master [who is usually a king or ruler].

This concept resonated with my Mozambican friends as they recognized that in this text we are not given an exalted status (such as a king), and neither are we attributed a lowly position (as slaves, for example). Instead, the creation account shows us that we were given the important steward role, a place of honor that falls under a still greater authority. Since the sin of the first humans was to usurp the authority of the true King of creation, an important step in addressing the core causes of poverty is returning to and accepting our role as stewards.

Second, the narrative reveals our proper rhythm. In the creation account we find God modeling the rhythm of work and rest that we are to follow (Gen 2:1–3). God chooses to rest and sanctifies the day as a Sabbath. The creator exemplifies a healthy pattern for his creatures: six days of work and one day of rest. When human pride and sin trips us and causes us to fall out of step—either into working all the time, “like a machine” as one Mozambican participant observed, or into laziness—then we have drifted away from God’s intended rhythm of life.

Third, this text reminds us of our responsibility. It is significant to note that work is a provision built into creation, not “a result of the Fall.” We are created to be hard-working stewards. While Gen 3:17–19 tells us that sin caused the work we do to be harder, it certainly does not negate the value of our work or indicate that our responsibility to work is a consequence of sin. The truth is that labor is a part of life as God intended it.

Beyond the reframing of humanity’s role, rhythm, and responsibility in the creation account over against the destructive power of sin, the book of Genesis also provides another story that illustrates orientations that either keep people trapped in absolute poverty or have the potential to enable them to escape it. In Gen 25:19–34, we find the strange account of Jacob and Esau. We are told that when Esau returned hungry from a hunting excursion, he came upon his younger brother cooking a simple meal. Famished, Esau agreed to trade away his birthright for a plate of food. While Jacob certainly could be critiqued for his lack of generosity and accused of “tricking” his brother, v. 34 indicates that Esau was ultimately culpable because he despised his blessing.

Besides birth order, there is a clear difference between Esau and Jacob. Their mindsets are vastly different. Jacob willingly forfeited food because of the promise of a greater gain, while Esau gave up a long-term blessing for a short-term reward. My Mozambican friends see in this story a parable that has similarities to the way Ruby Payne, in A Framework for Understanding Poverty, distinguishes between two types of poverty and their underlying causes:

1. “Generational poverty is defined as having been in poverty for at least two generations; however, the patterns begin to surface much sooner than two generations if the family lives with others who are from generational poverty.” Mozambican participants described this as a family where “it is not possible to find even one schoolteacher.” A young boy grows up learning from his uncles to live lazily and not be ashamed of drunkenness. Esau’s thinking pattern seems most prevalent in generational poverty. His selection of a short-term reward over the long-term gain seriously affected his children generations later, and his is a cautionary tale that illustrates how the consequences of choices we make today for good or bad can powerfully shape the lives of our descendants.

2. “Situational poverty is defined as a lack of resources due to a particular event (i.e., a death, chronic illness, divorce, etc.).” Mozambican participants noted that those in this group can recover faster because they think and act differently. One man wondered at the way these people could “suffer a bad crop, but within a year they are flourishing again. How do they do it?” Jacob’s orientation seems to be a key differentiator for people in this group. In the same way that he accepted hunger in the short term for the promise of a long-term blessing, those who are able to make sacrifices with a greater goal in mind are more likely to find success.

Makua-Metto participants recognized the distinction between these two types of poverty and the mindsets that reinforce them. They agreed that one of the key shifts in order to break out of absolute poverty is to value long-term rewards more than short-term ones. While that change in perspective may be easier to implement on the individual level, how does it work in the context of an African society where the social contract often dictates that the needs of the group are to be given primacy over the needs of the individual?

Thriving as the People of God: Instructions for Israel on Living Well Together

In this section, we will look at how God’s vision for prosperity and perspective on poverty were not limited to the individual level but were part of his objective for all of society. In Exodus 1 and 2 we see how God’s anger at the economic and spiritual oppression of the Hebrew people in Egypt led him to go to great lengths to deliver them. After the exodus, God established a covenant community where the economics of the whole society were carefully considered, and the expectation was clear that God would not accept worship from a people who neglected the poor.

As part of my research among the Makua-Metto, I interviewed Christians and non-Christians to get a broader range of perspectives. On one of these interviews, I sat with a group of Imams and asked them about the causes of poverty. “If we were to think of poverty as a symptom, like a cough,” I asked, “what would be the illnesses that cause it?” Those Muslim religious leaders observed that poverty has three causes in Makua-Metto culture: selfishness, laziness, and corruption. Upon further reflection they concluded that corruption is ultimately the result of selfishness and laziness. So, if poverty is the symptom, then the diseases are laziness and selfishness which often give birth to a further source of poverty, corruption. These three diseases not only cause pain for individuals, but also keep the community from becoming a kind of covenant community similar to the one advocated in Scripture.

In the Old Testament texts, God specifically addressed those three causes of poverty in Israelite society, giving his people a way to protect themselves and their communities from absolute poverty.

1. Safeguards against Selfishness. Selfishness had the potential to manifest itself in Israelite society in a number of forms, so the laws of Moses specifically laid out protections against its impact in terms of land, money, and food. One illustration that resonated with our Mozambican friends was the story of a friend of mine who built a triangular fence around a hand-dug well to keep his grandchildren from falling in. These laws were some of the means by which God created a barrier to protect the people of Israel from falling prey to the effects of selfishness on a societal level. In discussing these texts, we were careful to note that the laws given to Israel are not binding on us as Christians living under human governments today, but the principles and practices they reveal could have value in helping frame a life free from absolute poverty in our current context.

- Land and Jubilee. For the Israelites:

Land meant a future both secure and without anxiety. The viability of each family unit was based on ownership of a piece of land given to it as an inheritance. The Lord provided them with a good land (Deut 8:7–10). More important, land was a trust whose ultimate owner was God.

Since the land belonged to the Lord, it could not be sold permanently. The Jubilee provision meant that after a certain amount of time the land would go back to the original family (Lev 25:8–23). By faithfully implementing this safeguard, Israel would protect many people from falling permanently into generational poverty.

- Money and Debt Forgiveness. In Deut 15:1–11, we find God instructing the community to live in a way that “there will be no one in need among you,” while also still recognizing the reality that “the poor will be among you.” Debt has the power to strangle families, and God calls on his people to be generous in sharing. The haves are called on to help the have-nots, and for their faithfulness in passing on a blessing, they are promised a blessing from God. As Proverbs 19:17 states, “He who is kind to the poor lends to the Lord, and he will reward him for what he has done.”

- Food and Sharing. Israel is to leave food in the fields for the poor to collect (Deut. 24:19–22). Interestingly, the well-to-do are not instructed to give the poor a hand-out; instead they are to allow the poor to gather food on their own. One Makua-Metto friend noted how this provision would allow a person in a difficult situation to continue working to provide food for his family.

2. Lessons about Laziness. The book of Proverbs contains some the best object lessons and illustrations about the impact of laziness. We are told that laziness is more than just a bad habit, it is destructive (Prov 18:9). In the Makua-Metto village context, everyone knows someone whose laziness leads him to delay fixing a leaky roof on his mud hut. That laziness often ends in the destruction of the house. Proverbs 6:6–11 provided the most helpful visual as together we imagined God exhorting a lazy man to look up from his bed and observe a diligent ant passing by. Mozambican participants were able to come up with many examples from their own experiences about the dangers of laziness.

3. Critiques of Corruption. God has no patience for corruption. Proverbs 14:31 states it in this way: “He who oppresses the poor shows contempt for their Maker, but whoever is kind to the needy honors God.”

And the Lord warns people with power not to be corrupt. To those who plot this kind of evil, God promises that he himself will plot their ruin (Mic 2:1–2). To illustrate the destructiveness of corruption and structural injustice, we examined the story of Ahab stealing Naboth’s vineyard (1 Kgs 21). Our Mozambican friends commented on how Ahab’s selfishness and laziness caused him to forget God’s law and follow his wife’s corrupt advice. Queen Jezebel had no respect for God’s laws against injustice. Having grown up as a Sidonian princess, she assumes that kings should be able to take whatever they want and coldly ordered the killing of Naboth so that her husband could take possession of the vineyard. But God did not tolerate this wickedness and injustice; he sent the prophet Elijah to inform Ahab that his family line will be completely wiped out.

A beautiful contrast to that tale of corruption is the example of Boaz found in Ruth 2. Boaz embodies God’s commandments. He has a good relationship with his employees and generously leaves the edges of his fields for the poor. Boaz even goes beyond what is required of him to bless Naomi and Ruth. Boaz is not selfish, lazy, or corrupt, and God is honored through this man’s generosity. God in turn blesses Boaz, and he becomes the great-grandfather of King David (Ruth 4:13–22). Our Makua-Metto friends paid special attention to the way that God wiped out the descendants of corrupt King Ahab but richly blessed the line of Boaz, making it into a line of kings.

Mozambican participants enjoyed layering these instructions, counsels, and stories of selfishness, laziness, and corruption. While time-consuming, surveying these examples helped illustrate the just, covenantal society God intended for Israel. Examining them with fellow believers at this stage was an important step toward looking beyond individual wealth accumulation as the goal and developing their imaginations for truly thriving as a community and living well together. The foundation made from these insights plays an important role in the final section as we look at implementation of day-to-day principles and practices that contribute to a life free from absolute poverty.

Visualizing the Factors and Patterns that Affect Both Rich and Poor

Many Jews in Nazareth and Galilee during the time of Jesus lived under the economic and political oppression of Rome. Some people, by aligning themselves with the empire, benefited financially from the system. The New Testament’s economic and political history is easily relatable for our Makua-Metto friends. Mozambique suffered hundreds of years under Portuguese colonial rule, followed by a war for independence and a bitter civil war. Recognizing this similarity between Jesus’ context and their own seemed to give Makua-Metto participants further confidence to discuss ways that colonialism and war contribute to poverty and economic oppression. They have little difficulty imagining how the situation in the first century could make the poor look at the rich with both scorn (despising the way the wealth was gained) and envy (still assuming that wealth was a sign of blessing).

In leading discussions about absolute poverty with our Mozambican friends, I would walk with them through the Gospel of Luke to hear what Jesus had to say about poverty and money as he addressed both the rich and the poor. We used that backdrop to discuss their own perceptions of the relationship between wealth and poverty. While some people (especially Westerners) assume that there is no connection between the wealth of the rich and the poverty of the poor, many Mozambicans believe that there is a causal relationship: the haves benefit at the expense of the have-nots.

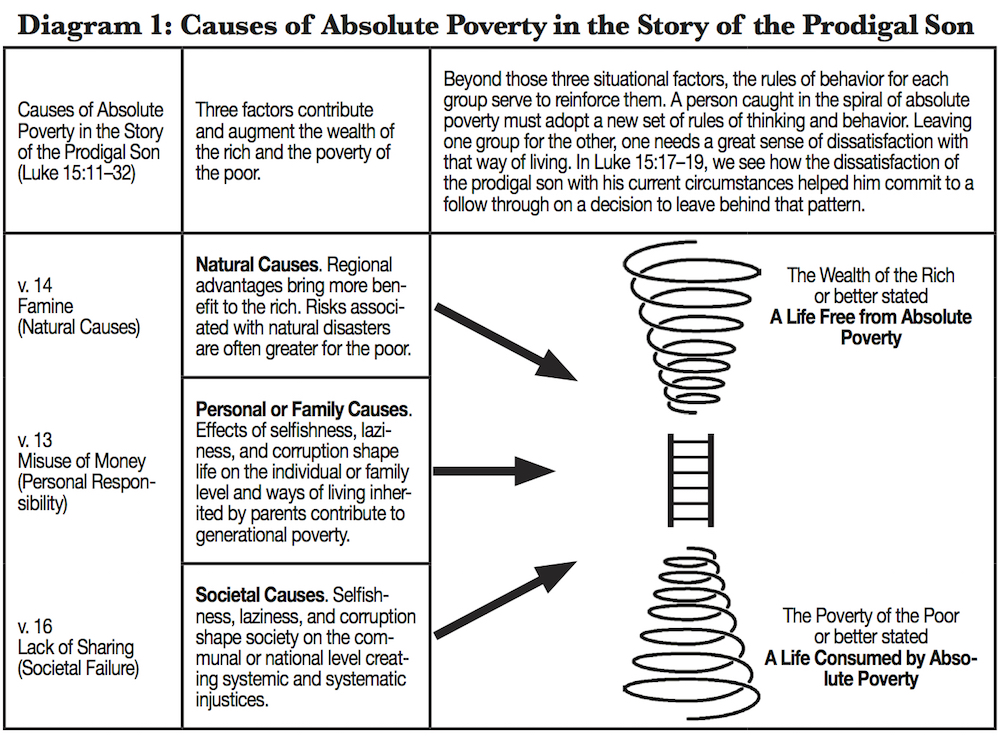

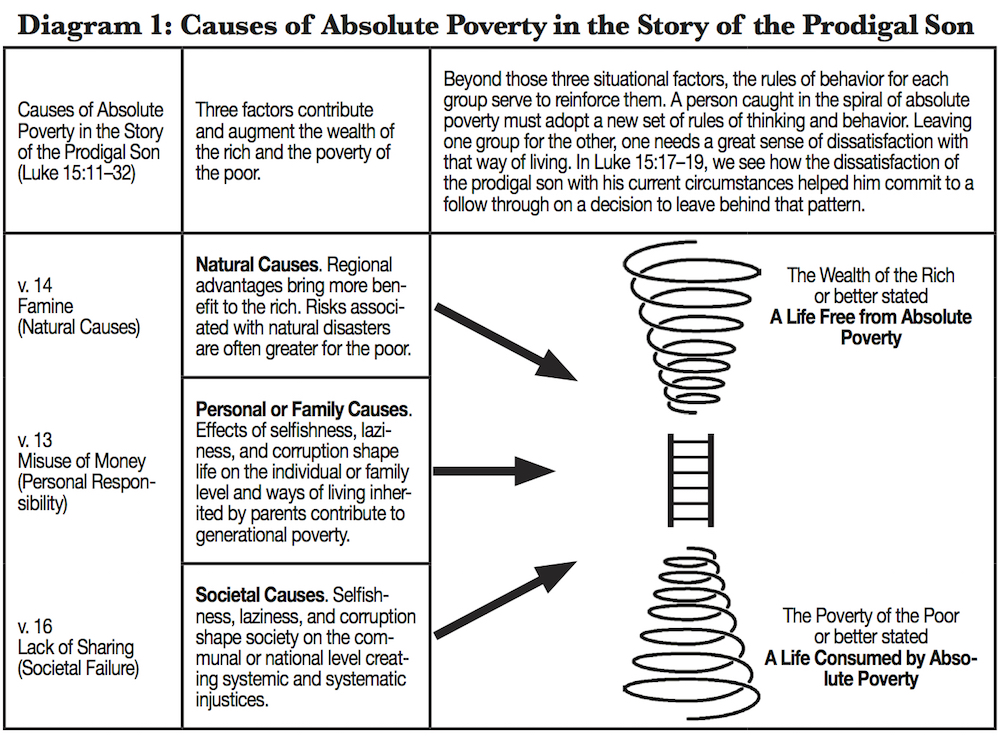

I found that an important step toward locals appreciating local solutions to poverty is their adopting a more nuanced understanding of the tension in the relationship between the poor and the rich. Without such an understanding, Makua-Metto people often give in to resignation and completely attribute their status as poor to fate or the sin of others. Surprisingly, the clues for a deeper perspective on the relationship between rich and poor can be found in the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32). In a fascinating experiment by Mark Powell, Jesus’ story was read aloud to people of different nationalities. Then they were asked the following question: “Why does the young man end up starving in the pigpen?” Most North Americans followed v. 13 and focused on personal responsibility, noting “he squandered his property.” Most Russians concentrated on v. 14, saying that his suffering was due to the “severe famine that took place throughout the country.” Yet, most of the Africans who participated in the experiment described the cause as a lack of sharing: “no one gave him anything (v. 16).” This intriguing study reveals much about our cultural biases, but it also can help us form a more accurate and holistic understanding of the causes of poverty and wealth. I created Diagram 1 to illustrate for our Mozambican friends the situational and behavioral factors that contribute to absolute poverty and a life free from absolute poverty.

Material poverty is attributed in the Christian Scriptures to both “self-imposed and externally imposed factors” depending on the circumstances. So, it is not that “the wealth of the rich” causes “the poverty of the poor” or that they are completely unrelated. Instead, patterns of behavior and natural, personal, and societal factors contribute to both.

Before we move forward, it is important to note that our Mozambican friends see poverty and wealth as affected not only by physical realities but also by the spiritual realm. To address poverty holistically, then, we will also need to name and discuss the powerful spiritual forces that are assumed to be present in the world around them: fate, evil spirits, and God. While space does not permit an exploration of these spiritual forces, it is important to note that a truth that resonated strongly with Makua-Metto participants was this: God especially loves the poor:

Scripture never says that God loves the poor more than the rich. But it does regularly assert that God lifts up the poor and the disadvantaged. And it frequently teaches that God casts down the wealthy and powerful in two specific situations: (1) when they become wealthy by oppressing the poor; or (2) when they fail to share with the needy.

So, corruption, selfishness, and laziness on the part of the wealthy will lead God to come to the poor’s defense. As our Mozambican friends and I sought to understand why God would be most concerned to protect the poor, one specific image was particularly meaningful. We imagined a mother with two daughters. One of her children is twelve years old while the other is only two years of age. If a dangerous dog approached, I asked, which child will the mother pick up and carry to safety? Clearly, she will protect the smaller one, confident that the larger child is more capable and fit to defend herself. While the above diagram and the nuances of the relationship between the rich and the poor were lost on some Makua-Metto participants, the vast majority connected well with the idea that God loves and defends the poor because he knows they need more help and assistance in time of trouble.

Which Game Are We Playing? Discerning and Leaving Behind Poverty Rules

Diagram 1 shows that a life free from absolute poverty and a life consumed by absolute poverty were influenced by external factors. Yet, we also saw that a set of internal rules or patterns of behavior reinforce each group’s status. In this section, we will look at two different games as an analogy with the internal rules found in each system.

Every game has a set of rules that players must follow. Two games with which our Mozambican friends are familiar are soccer and a game Makua-Metto children play called ayessi. In ayessi a bottle is placed on the ground, and one player tries to fill it with sand while a child on either side tries to hit her with a ball. If the child in the middle can elude them and fill the bottle first then she wins. But if she is pegged with the ball before the bottle is full then she has lost. After talking through the rules and objectives of each game with Mozambican participants, I ask them to imagine a person living in a village where everyone only knows how to play ayessi. One day, this man travels to a larger village and finds a soccer match taking place. Confused after watching the players kick the ball for a few minutes, he decides to join the game, runs to the middle of the field and begins filling up a bottle with sand. Then he excitedly jumps up and down, declaring himself the winner. My Mozambican friends laugh when I ask whether this man has won. “No, of course not,” they say, “he was playing one game while everyone else was following the rules of another.”

This game analogy is helpful for considering the hidden rules of poverty in the Makua-Metto culture. In the same way that people learn to follow patterns and rules depending on the kind of game they are playing, they also need to learn to use certain rules depending on the financial game they are playing. If one is playing by the wrong rules, there is no way they can win. Since “generational poverty has its own culture, hidden rules, and belief systems,” one of the most beneficial things we can do is to help people who are enmeshed in their invisible, complex cultural ecosystems discern their context’s rules of deep poverty.

In talking about the hidden rules of absolute poverty in Makua-Metto culture, I affirm that these rules contain good and bad elements. We acknowledge that many expectations and patterns of behavior served people well during Mozambique’s protracted wars, but we also note how in the modern economy these ways of living actually limit people. Very few people are reaping much real advantage from this game.

To teach on the rules of absolute poverty learned through interviews and experiences in this context, I developed the fictional example of a Makua-Metto man named Miguel and his wife, Paulina. They are people like those found in many villages who are stuck in absolute poverty. Their story and the rules of their behavior and practices are divided into three parts: money, work, and relationships.

Absolute Poverty Rules/Practices regarding Money

- Having money in his pocket makes Miguel anxious. He rarely has a realistic plan for his funds, and because of social pressures and expectations, when people ask for money he feels he must share with them. In order to reduce that possibility, he spends funds quickly, often on things that don’t bring much economic advantage. He acts fast so that no one will have a chance to ask him for the money.

- His wife, Paulina, assumes that hard currency cannot really be saved or accumulated (where is a safe place she could put it anyway?). She presupposes that cash is to be used for more immediate needs. She would save money by investing it in a house, a goat or pig, or even as a loan to someone else, rather than save it in the form of currency.

- If opportunities arise in times when the family has no cash, Miguel is not afraid to borrow funds in order to pursue them. Paulina thinks that everyone is in debt, and believes that taking out loans from others is one of the best ways to improve their standard of living. Currently, Miguel has many outstanding debts. Stepping out of his yard and looking around the village he no longer sees neighbors and friends; instead he can only think of the values that are owed to each of them. Ironically, Miguel assumes that debt and financial obligation strengthen relational ties, but the truth is that Miguel consciously avoids his neighbors because these longstanding debts bring him fear and shame.

Absolute Poverty Rules/Practices regarding Work

- This phrase loops in Miguel’s thoughts: “I’m poor . . . it is my destiny . . . there is no reason to work hard.”

- Miguel also thinks that agriculture is not a true profession. He tries to spend as little time as possible in his field.

- As soon as Miguel harvests his crops, he sells much of it to merchants. Unfortunately for Miguel, that is the time that the market is full of corn, and the price of corn is at its lowest. He earns very little, and tragically, a few months later he will buy back the very same corn he grew at a much higher price.

- When the harvest is complete Miguel thinks, “Now, I’m on holiday.” He spends his time lounging around and talking to people. A couple years ago he blew through his family’s earnings buying locally made alcoholic brew with a bunch of his “friends.”

- Paulina makes the following assumption: “Money received from others by means of a request has the same value as the money received in payment for work and services.” What she fails to realize is that asking others for money will obligate her to return the favor in the future. In reality she is just pushing off her personal labor to a later date, one where she’ll need to work harder to pay off the accumulated interest.

- Paulina has an uncle who is wealthy. Everyone says he got his money by means of witchcraft. So Paulina believes that if someone accumulates wealth, they probably used witchcraft to get it. She often contemplates using witchcraft for financial gain and ignores the fact that her uncle is constantly worried that someone will use witchcraft against him because of jealousy.

- Paulina’s uncle often says, “You should always take advantage of every opportunity, even if it comes at the expense of others! Remember: ‘the goat eats where it is tethered.’ ”

- One day Miguel tried selling small piles of charcoal outside their yard. When Paulina’s uncle came to visit, she felt ashamed and mocked her husband in front of the rest of the family, saying it was embarrassing for her husband to do business on such a small scale.

Absolute Poverty Rules/Practices regarding Relationships

- Miguel has the following mindset: “I must rely on a network of friends, family, and if possible a good boss. Trusted people are safer sources of funds in time of need than a bank account.”

- Paulina is afraid to reject someone who asks for money because she believes that a person with a good heart would never refuse a request from friends and family. Even if the person has planned poorly or has been drinking, Paulina is careful not to directly refuse them because she is afraid they will say that she is selfish.

- Paulina would not try to correct someone who has planned poorly and is suffering the consequences of those choices, because she sees discipline as being about penance and forgiveness, not really about changing bad behavior.

- Miguel and Paulina keep secrets from each other about money. They won’t even tell each other when they borrow money from others. Miguel hid some cash in a tin can in the dirt floor of one of the rooms of their house, and he will not let his wife sweep that room because he doesn’t want her to find it. Sometimes Paulina will keep her secret cash tied up in the folds of her wrap skirt. She will sometimes pull away from her husband when he tries to touch her so he won’t notice the lump the money makes in her clothing. This couple thinks it would be impossible to make a plan together about money and assumes that this way of keeping secrets is how all marriages must function.

- When illness or death strikes a relative, any available funds are used for medicine, travel, or food even though this severely sets back the couple’s financial plans and dreams. Miguel was frustrated because they had finally scraped together the money to pay their son’s school fees, but Paulina’s brother fell ill, and she gave all of it to help him travel to the hospital.

In the dialogue with Makua-Metto participants about Miguel, Paulina and the rules of absolute poverty, I was careful to note that not all of these practices are bad. At some level they work. But together they form a system that consistently keeps people in absolute poverty, and it is a way of life to which people have grown accustomed. They talked about the fact that while a few select people achieve some benefit from the system, most do not. And by continuing to follow the rules of this crushing game, people have little chance of escaping the gravity of absolute poverty. Miguel and Paulina follow the dominant culture’s norms and remain trapped in a system of absolute poverty. In the discussions about their examples, Makua-Metto participants were not interested in parsing whether these ways of living caused absolute poverty or were symptomatic of absolute poverty. Instead, they consistently expressed that this story described the reality they felt trapped in and desired help thinking through how to implement the biblical principles they had studied earlier into their own lives.

It was then that I was able to point out how while many people were playing the absolute poverty game, there was a subset of people in this culture who were living by a different set of norms. I shared the findings from my qualitative interviews of practices and perspectives in connection with biblical concepts in the following stories of Ali and Joana. They are people like those found in any village, but their patterns of behavior are helping them escape from absolute poverty. Again, the alternative norms in the following list are not “outside” solutions of an external agent solving the local problems, but inside solutions that emerge from the thought and practice of local agents. I have simply collected these practices, reorganized them, couched them in common metaphors, and highlighted their connections to the ways of the kingdom of God.

Rules/Practices about Money that Contribute to a Life Free of Absolute Poverty

- In order to save money, Ali participates in an estik or nancunawe with a few trusted friends and colleagues. This group meets regularly, and each member pays a predetermined amount into a common pot. Then participants take turns receiving that amount. Having larger amounts of cash at one time like this enables Ali to make smarter, planned purchases or buy things at a discount.

- Ali and Joana have stopped borrowing money from people. As much as possible they are trying to avoid debt. Once, they went to a seminar at their church, and the speaker taught Rom 13:8 (“let no debt remain outstanding, except the continuing debt to love one another”) and Prov 22:7 (“the borrower is servant to the lender”). The person leading the seminar also said something that really stuck with them: “Some people borrow money thinking it is an advantage, but you’re really only ready to seize financial opportunities with your own assets, otherwise you’re chasing profit backwards. This is because you still have to pay back the loan. By borrowing money you are doubling your risk. Let’s say you spend 1,000 meticais to buy something. If it is stolen or broken and you borrowed money to get it you will now have a debt of a thousand meticais (-1,000) instead of just being back at zero (0). That’s a huge difference.”

- Joana’s uncle often gave her this advice, “Be careful not to abuse your position or take advantage of others. While some justify corruption by saying, ‘The goat eats where it is tethered,’ you must remember that you are not a goat—you are a person! God wants you to prosper with justice. Don’t try to get too much for yourself; be content with what is sufficient. As Prov 23:4 says, ‘Do not wear yourself out to get rich, have the wisdom to show restraint.’ ”

- One day Joana’s uncle came to visit and found Ali selling alcohol. At the end of his visit he sat down with the couple and started by mentioning the example of the famous Mozambican Olympian, Maria Lourdes Mutola. “I remember watching videos of her running the race,” he said. “She did not trample others. She did not try to trip her fellow racers. And still she was able to win many races. Let me advise you to live with justice and not mislead anyone. Stop selling products that will trip up and trample your neighbors. Continuing to run in this way by selling alcohol to your friends will not ultimately help you win the race.” Ali and Joana were convicted by this and stopped selling those products.

- Therefore, Ali had to start his business all over again. He felt ashamed to sell small piles of charcoal but Joana encouraged him that most business starts that way. “Our child was not born fully clothed and strong. No, he was born small, naked, and unable to speak or walk. But we did not reject him or find him strange. We were happy with the child. My husband, we should not feel shame in starting this business in a small way.” Ali listened to her encouragement, and they have rejoiced together in watching their business gradually grow.

- One day Ali and Joana were in the city visiting her uncle. Ali asked for advice on managing the finances of the family and the business. Her uncle started by saying, “You should always protect your ‘seed fund.’ ” “What’s that?” Ali asked. “You know how every farmer will store his best seed until the time for planting? Even if this farmer is on the edge of starvation, he will not eat that corn. He must save it to plant next year and no one thinks it strange that he acts that way. You should have this same attitude with the seed money necessary to continue your business. That seed money should be set aside first, then use your profit to pay for further expenses and necessities and to share with others. Too many people strangle their business at the beginning by not protecting their seed.”

- “Okay, how do we protect our seed?” Joana asked. Her uncle replied, “Imagine a pair of pants with four pockets. You should divide your money, organizing it and keeping it separated in a system of ‘pockets.’ The first pocket is for your seed money—the funds needed to continue your business. For example if your little store requires 700 meticais to restock it, then your first 700 meticais should go straight into that pocket. Your profit then should be divided into the remaining three pockets. One of those pockets is for expenses (used to purchase food, salt, soap, etc.). One of the pockets is for giving away—money you are tithing to the church and money set aside to help others. Then your last pocket is to save for future projects. It takes much discipline to respect the pockets. There are times when you’ll not be able to do certain things because the money in that pocket has already been paid out.”

- “But above all, in your quest to grow financially,” Joana’s uncle continued, “remember that while material goods can be a blessing, they can also be a danger. We should carefully consider the implications of the fact that twice as many verses in the Bible deal with money than faith and prayer combined. Jesus himself issued a clear warning in Luke 16:13, reminding us that ‘no one can serve two masters. . . . You cannot serve God and money.’ Money, like fire, can be used for good and evil. We must carefully consider the way we get it and use it. In the same way that fire can be attained in a variety of ways, we know that money can be gained in a number of ways, too. There are basically three ways to get money: 1. Work – make a product or provide a service. 2. Gift – receive an offer or inheritance. 3. Loan – borrow money on a promise to return it. This last way to receive money is not advisable. And in the same way that fire can be used in many ways, money can be used in various ways, too. There are three ways to utilize money: 1. Spend – use money to buy things. 2. Save – put aside for a long-term goal. 3. Give – This third one is important because giving at least a tenth or tithing is a way to show God that we submit to him as our King and Lord. It is important to sit down together and consider carefully what money is coming in and what money is going out. With this kind of control, you are not letting your money master you, instead you are the master of your money and you can use it in ways that honor your Master.”

Rules/Practices about Work that Contribute to a Life Free of Absolute Poverty

- Ali and Joana believe that all able-bodied people should work for their living. One Sunday they heard a sermon that quoted 2 Thessalonians 3:10: “If a man will not work, he shall not eat.” Ali’s friend Rafiki is addicted to and spends all his money on marijuana. Joana has grown impatient with him. “His nose always seems to know when I am cooking,” she told her husband. “Rafiki shows up even when you are not at home and expects food to be given to him. I want to stop sharing food with him until he stops smoking marijuana.” The couple agreed on this course of action. So, the next time Rafiki showed up at the house he was told of their decision. He got mad and left to wait for food at another house. A few of the other neighbors have begun following suit. Nowadays, while Rafiki has not quit marijuana completely, at least his hunger has led him to work on his farm.

- Ali once attended a sustainable agriculture course taught by a Mozambican church leader. There he learned the importance of doing work at the proper time. “God did not create a disorganized universe. We know that in this part of the world December 22nd is the day of maximum sunshine, so we should organize our planting to take advantage of this. To do that, we’ll need to sow our seed in late October and November in order to have the greatest harvest in the end.” Ali began thinking of ways this commitment to do things at the proper time could impact other areas of his life. He convinced his wife that instead of making fried bean cakes to sell every day of the week, she should only make them on Saturdays when there is a soccer game in the village and many people will buy them. In the past the family lost money because of the ones that would not sell. By making and selling the cakes at the proper time, Ali and Joana have begun making more money and wasting less resources.

- At that agriculture seminar Ali also heard, “Do everything with excellence. When you plant carefully and space the rows properly, it actually means less weeding work for you. As your plants’ leaves fill in the spaces, the grass and weeds won’t have access to sunlight. Working with excellence will improve your production!” Ali has applied this principle to other areas of his life, as well. Instead of seeing the months after the harvest as his holiday, he has adopted a different weekly pace: six days of work and one day of rest. While many people are resting after the harvest, Ali uses that time, while people have money, to do jobs that others don’t want in order to improve his family’s finances.

- Another thing that Ali heard at the farming seminar is this: “Do everything with joy. When we work with joy the work is easier and is a blessing to us and others.” One day, Ali saw Joana’s brother in the city selling cellphone airtime to people on the street. Ali noticed that Joana’s brother was not treating his customers well. His face had a sour expression, and he was not being kind or helpful, preferring to joke around with the other vendors. It almost seemed as if the customers were bothering him! Ali bought him a coke, and they sat and talked about how his business of selling airtime was going. Ali brought up the example of a nearby town where many men have gone to dig for rubies. “Brother-in-law, how would someone treat a hole where he consistently found rubies? Would he throw trash in it or cover it up? No! He would take care of it and protect it, wouldn’t he?” Ali motioned to people walking down the street. “These customers who buy airtime credit are your source of rubies. You must take care of them. Serve them well and with joy, and your business will have more success.” The young man listened to his advice and began smiling and chatting with his customers and encouraging them to buy from him. Nowadays, many people will pass up other vendors to buy from him. His joy in serving others has led to growth in his business.

- One day Joana’s uncle asked an important question: “Ali, what advantage is there in selling while everyone else is selling, and buying while everyone else is buying? Wouldn’t you make more profit by finding a way to buy when everyone is selling and the price is lowest and sell when the price is highest?” Ali realized that food is a kind of commodity, and a person who can store a crop has the advantage of selling it at a later date. He found someone to teach him how to store and treat his corn for bugs and sell most of it only when the price is at its highest.

Rules/Practices about Relationships that Contribute to a Life Free of Absolute Poverty

- Joana is glad to help other people. But when the sharing pocket runs out of money, she feels justified in saying no because of the plan she and her husband made to protect their seed money. Joana and Ali are trying to practice wise generosity. Once, Ali read a biblical passage that has helped him a lot: 2 Cor 9:7–11. In v. 7, Ali saw that people should give with a good conscience, informed by the Holy Spirit. That helped him feel free to share at the right time and to refuse in an appropriate way if he did not feel good about it. Last week the sharing pocket was empty and Joana refused a request from her own brother. This is extremely hard and takes courage.

- Joana has begun thinking of her home as a small business. She keeps track of food and resources that come in and food and resources that go out to confirm that what they have is best serving and helping her team—her husband and children—win together.

- Many men just look at a woman’s external beauty in evaluating a potential spouse. Among the Makua-Metto there is no traditional wedding ceremony and men and women will marry quickly and divorce quickly. Ali realized that a good wife is one who can hold onto (secure) and grow (stretch) the family’s resources. Ali is not gifted with handling money, but he recognized that Joana is very good at saving money. Last year he entrusted her to hold his money for him until it was time to travel to a regional church conference, and when the day arrived, his wife handed it over with gladness. From that point on, Ali began praising his wife’s talent for keeping money safe, calling her the pet name, “my bank.” Makua-Metto men whose families live free from absolute poverty consistently say that their wives are great at faithfully conserving money.

- Once during a visit, Joana’s uncle asked them, “Which families in this village are living free from absolute poverty? How many years have they been married?” As they reflected on this question, they realized that all of those couples had been together for at least 15 years. Her uncle continued, “Divorce is expensive and will chew through any wealth one possesses. It will demolish financial possibilities and push all parties involved towards the cliff of absolute poverty. On the other hand, a couple that has been married many years has the greatest opportunity to accumulate wealth. Therefore, a husband and wife have a huge financial incentive to protect their home.” Each week Ali and Joana sit down and look together at their finances. They pray together and ask God to help them with their needs so they can bless others more (Jas 4:1–3). They decide together what they will spend on food and clothes. They have a long-term financial goal. Hearing in church that God enjoys blessing those who are generous (Mal 3:6–12), they have decided to experiment and give a tenth of their income to the church for a year. One Sunday, Ali did not have the courage to give as much as they agreed on. So he called Joana to step outside the church building for a moment and asked her to be the one to give the offering that day. Since they made the financial plan together, Joana enjoys using her gift of faithfulness with money to help her husband.

- Ali and Joana understand that the church at its best functions like a communal safety net. When people live on the edge of absolute poverty, it is easy to slip and fall off the high wire. In the Makua-Metto context, it is impossible to live well alone, and sharing is a key value. This is also a deep value for the people of God. “Koinonía means first of all, not fellowship in the sense of good feelings toward each other, but sharing. It is used in that sense throughout the New Testament.” Ali and Joana must have reliable people forming a “network” that will share appropriately and catch each other when they fall. They are glad to be a part of a Christian community that supports one another in the following ways: (1) Sharing spiritual resources and praying for each other to do well. (2) Sharing financial resources when there are needs. (3) Sharing information, experiences, and contacts to help each other get ahead.

- But Ali and Joana know that not all communal activities serve as an effective support network. In the Makua-Metto culture, there is a practice called matanka where a family who has lost a loved one is expected to put on a feast for many mourners. This only adds to the suffering of those who are hurting. Not only are they mourning the death of a close relative, they also are expected to spend huge amounts of money on the feast. Protestant churches in Cabo Delgado have taken a stand against this practice and instead of expecting to be fed well at funerals, they intentionally bring an offering to share with the family. Sometimes when Ali is asked why his church does not do matanka (a common question in this mostly unreached area), he explains that the matanka of the surrounding culture does nothing to provide a safety net for those who are suffering but that his church does a different type of matanka feast—a matanka of love. Ali highlights how the way his church community brings an offering to help the family who is hurting serves as a safety net and reflects what true religion is all about (Jas 1:27).

Conclusion

The Bible does not offer a blueprint for fighting poverty, but its pages describe ways in which God takes sides with the poor and champions their cause. The church is called to address both the symptoms and the root causes of poverty at structural, communal, and personal levels. Describing and prescribing that gigantic task is certainly outside the scope of this article. My hope is that this paper goes beyond the typical categories of poverty resources (helping westerners understand poverty or advocating a silver-bullet approach) and instead serves as a practical supplement for those attempting to assist the poor in meaningful ways. While this article outlines an approach specific to the Makua-Metto people of Mozambique, my conviction is that long-term kingdom workers can serve and bless the poor by listening closely and helping them name local solutions. They can also do much good by pulling back the curtain on how norms of behavior they are familiar with can fit within a system free from absolute poverty as well as being in line with the kingdom of God.

Alan Howell, his wife Rachel, and their three girls live in Montepuez, Mozambique. Alan has an MDiv from the Harding School of Theology. The Howells have lived in Mozambique since 2003 as part of a team serving among the Makua-Metto people. They blog about life and ministry in Africa at http://howellsinmoz.blogspot.com.

Bibliography

Ajulu, Deborah. Holism in Development: An African Perspective on Empowering Communities. Monrovia, CA: MARC, 2001.

Austin, Michael J., ed. “Understanding Poverty from Multiple Social Science Perspectives: A Learning Resource for Staff Development in Social Service Agencies.” Bay Area Social Services Consortium. University of California, Berkeley. August 2006. http://cssr.berkeley.edu/bassc/public/completepovertyreport082306.pdf.

Collier, Paul. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can Be Done about It. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Easterly, William. The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. New York: Penguin, 2006.

González, Justo L. Faith and Wealth: A History of Early Christian Ideas on the Origin, Significance and Use of Money. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2002.

Gordon, Graham. Advocacy Toolkit: Understanding Advocacy. Roots Resources 1. London: Tearfund, 2002. http://inspiredindividuals.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Understanding-Advocacy.pdf.

Greer, Peter, and Phil Smith. The Poor Will Be Glad: Joining the Revolution to Lift the World out of Poverty. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009.

Hall, Douglas John. The Steward: A Biblical Symbol Come of Age. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990.

Howell, Alan. “Turning It Beautiful: Divination, Discernment and a Theology of Suffering.” International Journal of Frontier Missiology 29, vol. 3 (Fall 2012): 129–37, http://ijfm.org/PDFs_IJFM/29_3_PDFs/IJFM_29_3-Howell.pdf.

Maranz, David. African Friends and Money Matters: Observations from Africa. Publications in Ethnography 37. Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2001.

Middleton, J. Richard. The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2005.

Myers, Bryant. Walking with the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development. Rev. ed. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2011.

Payne, Ruby. A Framework for Understanding Poverty. 4th ed. Highlands, TX: Aha! Process, 2005.

Powell, Mark. What Do They Hear? Bridging the Gap between Pulpit and Pew. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2007.

República de Moçambique. “Plano de acção para redução da pobreza absoluta, 2001–2005.” Versão final aprovada pelo conselho de ministros, Abril de 2001. http://www.ilo.org/public/portugue/region/eurpro/lisbon/pdf/moz_parpa.pdf.

Sachs, Jeffrey. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time. New York: Penguin, 2005.

Sider, Ronald J. Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger: Moving from Affluence to Generosity. New ed. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2005.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do about Them. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2015.

United Nations Development Programme. “Mozambique.” Human Development Reports. http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/MOZ.

Wright, Christopher. Old Testament Ethics for the People of God. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004.

Yunus, Muhammad. Banker to the Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle against World Poverty. Philadelphia: PublicAffairs, 2007.