How can bioregionalism cultivate an enviro-missional imagination? Watershed discipleship is a local bioregional response to ecological crisis, but the watershed may also be extended into a theological framework that addresses the destruction of the uninhabited spaces of air and water called the global commons. Because industrialized humanity suffers from placelessness (ignorance about its global context), it cannot trace the effects of the waste it dumps in the places beyond the horizon, so it forgets about them. Placelessness leads to societal amnesia. By imaginatively integrating scientific, mythic, and philosophical concepts, this essay develops a bioregional response to the problem of the global commons. The author argues for local myths that are informed by global ecological systems and founded on a relational worldview that resists the societal amnesia induced by industrialization and cost-benefit analysis.

Something black rose from behind them, like a smudge at first, then widening, becoming deeper. The smudge became a cloud; and the cloud divided again into five other clouds, spreading north, east, south and west; and then they were not clouds at all but birds.

from The Birds by Daphne du Maurier

The apocalyptic film , by Alfred Hitchcock, reveals a deep-seated fear of what is beyond the horizon. Adapted from Daphne du Maurier’s short story, the film takes place on the edge of terrestrial habitation. In Hitchcock’s film, the birds come from beyond the horizon. Over the course of the film, thousands of diverse species show up on the doorstep of human civilization, hungry for human blood. In the film as well as the short story, the birds peck the human eyes as a symbolic attack from forces that come from beyond visual perception. As creatures of the wind, birds have the unique evolutionary capacity to travel beyond the world of terrestrial, two-legged humans. Tapping into an ancient fear not of birds but of natural apocalypse, Hitchcock re-mythologized chaotic natural processes that seem to communicate vengeance. Like the First Testament’s plagues, the story describes nature preying upon human civilization. The Birds is rooted in a real event that occurred in Santa Cruz, California, during the summer of 1961. Hitchcock researched the event during the initial design phase of his film. Hundreds of sooty shearwaters crashed into windshields, windows, and buildings; thousands of dead shearwaters covered streets. Needless to say, the birds did not fly around tearing the eyeballs out of people.

With one of the longest migratory patterns among birds, shearwaters cover up to 39,000 miles annually. As a non-sedentary species, shearwaters are creatures from beyond the horizon. The orientation of their life history revolves around travel patterns between breeding and feeding grounds. The 1961 event in Santa Cruz remained a mystery, but many suggested the strange mass fatality was rooted within the chaotic seas. Scientists have hypothesized that the shearwaters had been poisoned by a substance called domoic acid that recently has had detrimental effects on humans.

These malevolent effects came to light in 1987 when a mysterious food poisoning outbreak hit Canada. Epidemiologists traced the ingested food to blue mussels harvested in the eastern waters of Prince Edward Island. Officials were confused by the unusual symptoms such as short-term memory loss, confusion, and death in some cases. Over the next few years, discovering the substance and origin of the poison proved to be an ecological murder mystery with many twists and turns. In the end, investigators found domoic acid to be the cause. Today the symptoms are called “amnesic shellfish poisoning” (ASP). Within a category of related eco-toxic substances, ASP can come from eating shellfish at key moments in the movement of energy in oceanic trophic systems. Succinctly stated, domoic acid and other similar toxins are expressed in dinoflagellates and diatoms. The allelopathic poisons serve a similar function that poisons serve in terrestrial plants—defense against predation. As filter feeders, shellfish are not affected by the poisons but store the compounds. Consequently, the concentration is magnified. Known as bioaccumulation, toxins often become concentrated in fat stores that, when ingested, have detrimental effects on the predator. The behavior of shearwaters in Santa Cruz can be explained by an overdose of domoic acid.

Dinoflagellates and other plankton are located at the base of a massive oceanic food web. Moving from the oceanic deep to the surface during various life cycles, plankton populations and species diversity are fundamentally determined by available nutrients within the system. During massive phytoplankton blooms, allelopathic toxins become concentrated, killing various types of predators including fish that swim through the blooms. Further, the toxins often become airborne as the wind disturbs the surface of the ocean and blows microscopic plankton into the air with the sea spray. During such unique events, coastal residents often suffer with intense allergy attacks from the wind-borne poisons.

Recently, changes in phytoplankton assemblies—both specie variety and population size—have been observed. The chaotic system of specie assembly, allelopathic expression, and massive phytoplankton blooms has only recently been statistically linked to global warming and nutrient loading from terrestrial agriculture. Many dangerous blooms occur just off the coast of areas where anthropogenic nutrient-loaded waters are dumped into the seas. Interestingly, the nutrients are the excess of city waste or chemical fertilizers.

Hitchcock’s film and the 1987 discovery of the ASP outbreak serve as a kind of realized natural apocalypse. The film mythologizes, while the ASP outbreak parabolizes. The psychological thriller mythologizes a fear from beyond the horizon, while the ASP outbreak traces the cause and effects of industrialization on the placeless human global commons, particularly sea and air. The ASP outbreak describes the realization of a modern perspective on the global commons—a worldview which establishes the failure of industrial humanity to care for the uninhabited spaces that constitute the global commons. The effects of such a relationship with the global commons loop back from the mythic horizon and enculturate a profound memory loss in industrial cultures. This vision elucidates the need to cultivate a missional imagination robust enough to react to industrial myopia and cultivate ecological activism that verbalizes indigenous reconciliation with the primordial that dwells beyond the horizon. Bioregionalism is one fertile field for cultivating this relational re-imagining of the global commons that can value indigenous theology rooted in local ecology. The concern governing my entire exploration will be how bioregionalism, as both a philosophy and social activism, can provide a linguistic structure for an indigenous enviro-missional imagination. Considering the profound impact the corporate individual has on the global commons, any bioregional movement must concern itself with more than simply the local watershed. To that end, I will integrate mystical, theological, and ecological perspectives of the global commons that I hope will goad literate people into a renewed perspective on the great uninhabited spaces. The global commons are more than the fisheries of the great upwellings and more expansive than the polluted airs surrounding urban areas. Rather, the global commons are ecological verbalizations of the primordial. How does one protect the air? How do communities transfer environmental angst into action? How do bioregional activists defend expansive uninhabited spaces? The first step is to foster a bioregional cosmology.

The Extended Phenotype of the Industrial Human

Nutrient overload (eutrophication) is the main cause of the worldwide increase of harmful algal blooms (HABs). Furthermore, research confirms HABs’ increase is humanly generated (anthropogenic): due to the agricultural and waste management practices of modern habitation. Eutrophication is a peculiar effect of human behavior rooted in the placeless cultures of industrial capitalism and globalization. This behavior is both an extreme localism (a kind of hermeticism) and also a placelessness (exhibiting an ignorance of context). The flush of a toilet from a residence or the flush of fertilizer from a corn field are beyond the responsibility of the individual. Fecal matter and fertilizer move beyond the horizon to the mythical beyond; ignoring what is carried away by water, modern humanity only considers materials that are quantifiable within political, city-state boundaries. Further, by the arbitrary creation of borders and property, humanity loses a sense of responsibility for connected global processes. Eutrophication is a symptom of global industrialization, which ignores the consequences of human productivity within a larger world. I want to argue that eutrophication and other results of human (un)inhabitation are a kind of extended phenotype of the industrial human.

Evolution is measured only when scientists define the unit of selection. Selection since Darwin has been defined according to fitness of the individual as a unit. In 1982, Richard Dawkins coined the term “extended phenotype” to describe a different unit of selection—genes.

The phenotypic effects of a gene are tools by which it levers itself into the next generation, and these tools may “extend” far outside the body in which the gene sits, even reaching deep into the nervous systems of other organisms.

According to this perspective, the battle of fitness occurs inside the individual organism instead of between individuals. The self-replicating gene, argued Dawkins, is a kind of archetype that expresses its visual phenotype as behavior or morphology. Instead of the organism fighting for dominance, the body of the organism is a tool for genetic propagation. In this sense various alleles represent the competitive field of Darwinian dominance. The result of the genetic battle is the momentary extension of a specific allele within an organism and providing the fittest phenotype. In essence, the phenotype is the visual extension into the macro-world of a micro-dictated pattern. For Dawkins’s extended phenotype, the extension does not stop at the borders of the individual; phenotypes can extend into the larger world outside the individual. This extension can be expressed in other organisms, including completely different species. Often the phenotypic extension alters the behavior of other organisms beyond the carrier of the gene. Beyond this, the extension does not stop with the biotic, but can extend out to the abiotic environment and shape the structure of habitats.

Further, since organisms represent successful combinations of coordinating genes, some have suggested the individual organism is a kind of macro-composite phenotype. The composite phenotype represents a cursory boundary in which genes reach a coexistence with other genes; the organism represents a miniature stable ecosystem. In the end, the ultimate quest for the origin of speciation appears to be a circular mirage in which the genetic archetype emanates but also returns. As the arche emanates outward, it interacts with other factors until a composite phenotype is expressed. Many such phenotypes express niche construction in which the environment is changed. Earthworms, beavers, and humans are lucid examples of species that construct niches out of abiotic materials. Proponents of niche construction, however, suggest the extended phenotype can extend back upon itself. As the phenotype extends into the environment, the world turns inside out; the internal arche reveals itself as enveloping the outside. Yet as the enfolding occurs, the environment conditions the inhabitant and provides pressure on genetic selection.

The extended phenotype can help interpret modern human activity. Lacking only empirical evidence to determine the extent of genetic evolution, geneticists have evidence to show how human culture has a profound impact on genetic selection and its related phenotypes. One of the best examples with ample research is the allele of lactose tolerance. Present in only human populations which have had a historic tradition of dairy farming, lactose tolerance was expressed only after the practice of dairy farming was initiated. As a technology of production, domestication and animal husbandry represent a composite phenotypic package that provides the niche for dairy production. Dairy culture, as a stable tradition transmitted to future generations, represents a habitation or niche cultivated from a composite, extended human phenotype. However, the extension of the phenotype boomerangs back into the human as pressure selection for the lactose tolerant allele. As the ecologist Kevin Laland explains, “The selective environments of organisms are not independent of organisms but are themselves partly products of the prior niche-constructing activities of organisms.”

How does the extended phenotype help explain the ecological quagmire of global industrialization? As masters of production, humans are the ultimate niche engineers. In view of the capacity to shape the environment around us, environmental determinism is untenable. Thus, like the skewed model of linear evolution only originating within the gene, human culture is not simply determined by the environment. For some, the archetypal coding of culture seems to replicate within the mind. However, the cyclical extension of the phenotype back upon itself provides a more nuanced way to understand human behavior. Culture is both a product of the arche within the mind and a byproduct of the chaotic repercussions of niche construction.

Specifically, the speed, quantity, and scope of modern human behavior characterize the niche of globalized industry. When production is quickened and quantified for non-regional consumption, a cultural niche is produced. Like any other organism, humans produce resources for habitation; the construction of niche represents a new organization of environmental materials and spaces. The non-regional gaze of industry fixes upon the consistent, rapid, profligate production necessary to feed infinite desire. Consequently, as a hallmark of globalization, time and space are compacted. Resources created over millions of years are decimated within seconds, and artifacts of human production are extricated from tradition to be artifacts without time. As time implodes, the overabundance of industrialization homogenizes space by flattening landscape into a non-referential nowhere. Johannesburg and Nashville are the same place. Not only can I travel there in the blink of an eye, but I can easily confuse both places as the same place. Summarily, the niche of industrialization is a kind of expansive, liminal, and timeless nowhere. Ecologically described, the industrial human niche is a phenotypic extension marked by over-production and indicating a species near extinction. The replicating industrial arche is exploding into the world and mixing with a complex planetary system to create a niche that has profound effects on human fitness.

Returning to the story of ASP, industrial production replicates locally, but flows beyond the horizon to a place we know not—the desert oceans. Furthermore, industrial production moves into the uninhabited global commons to sit on the face of the deep. Mining and defecating within the unbounded commons, the extended phenotype of modern cultures cultivates a niche in the beyond. The human niche has exploded into the uninhabited world; shock-waves have stirred the face of the deep. As it explodes into the global commons, humanity cannot trace the effects. In this sense, global industrialization has cultivated a niche for humanity that selects for amnesia. In a timeless, placeless existence, the allele for human memory is profoundly weakened. As overproduction extends into the global commons, the primordial space develops allelopathic toxins of amnesia. This amnesia is both obfuscation and myopia. Like an overloaded field of fertilizer, the wastes of industrialization journey to the place beyond the habited—beyond the horizon. The pathway and its effects are obfuscated due to the chaotic complexity of global air and water. Yet, global air and water are not only the wasteland for industrial defecation but also the source of continued production. Like any niche, the environment provides the structure both for energy that leaves the organism and energy that an organism consumes. Humanity cannot trace the effects; and so, obfuscation becomes the germ of a mental myopia that results in societal amnesia.

The Global Commons

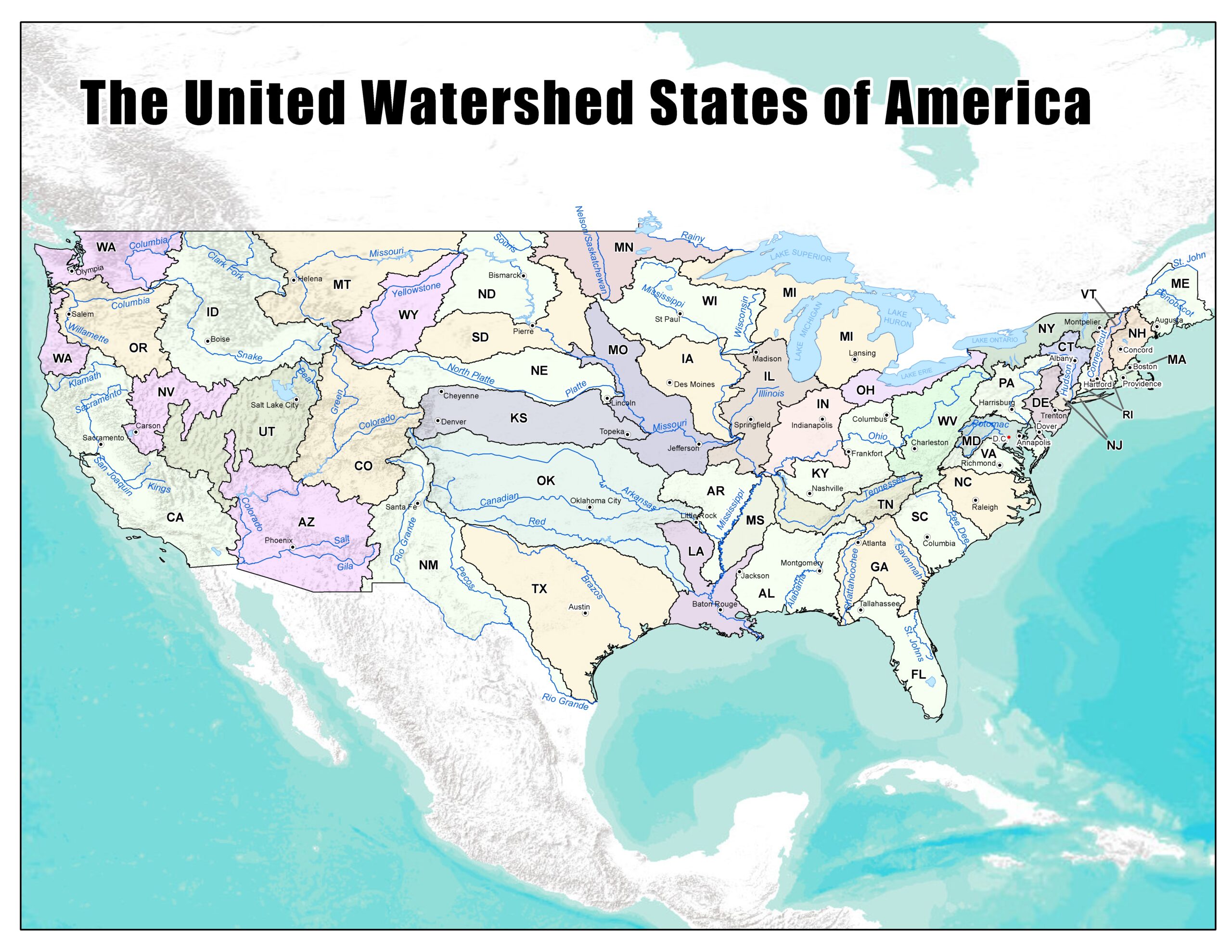

By emphasizing the watershed, bioregionalism rightly reorients human perception. Individuals must not only take responsibility for the field they own but for the location of their field within a flow of energy. Whether an individual lives in the uplands of a catchment area or the fluvial flatlands, energy moves from sky to sea and back again. Further, bioregionalism suggests nation-states are inadequate to provide sustainable living. Human life must be placed within a larger watershed than a district, county, or state. Nevertheless, bioregionalism identifies an ecological boundary. Indeed, these frontiers are real and applicable, but the placeless processes of water and air, and wandering lifestyles such as the sooty shearwater’s, require an extension of bioregionalism into a global, mythic space.

International corporations have already defied the boundaries of nation-state and operate in the global airs and waters of planet earth; industrial economies operate on global scales. The quantification of city waste and industrial agriculture are examples of a pervading ethic within placeless globalization. The global commons are uninhabited spaces where industrial economies dump excesses as well as mine abundances. The global commons are different than the terrestrial commons of lake and pasture. Regulated commons have definable boundaries, inhabitants, and access. On the other hand, global commons do not have clear boundaries, do not have human habitation, and do not have non-technological access. From an ecological perspective, the global commons are at once massive reservoirs of energy and conveyor belts of energy. From a cultural perspective, the global commons are at once mythic spaces beyond human boundaries and wild spaces beyond human control. Integrating the two perspectives, the global commons are the locus for ecological cosmology, where chaos and memory are rooted.

Reading Luce Irigaray

Boundaries are very important to bioregionalism as an interdisciplinary movement that uses geography to spatialize space. In fact, the delineation of an ecological border is what provides the first indications of place. For example, Robert Thayer defines the first characteristic of a bioregion as “a physiographically unique place, a geographically legitimate concept, an identifiable region, and an operative spatial unit.” The description of place inevitably requires differentiation over against other landscapes, concepts, and ecologies. To cultivate robust, sustainable human communities, it is imperative to identify place. Nevertheless, there can be a forgetfulness or amnesia of the constituents from which place is constructed. Following the suggestion that the global water cycle is a kind of placeless process, Luce Irigaray provides a critique of Western philosophy that can aid in relocating the global commons within Western culture. Irigaray argues Western philosophy has a type of amnesia that marginalizes the birthplace of life. According to Irigaray, Martin Heidegger’s meditation on the relationship of Being to place is a kind of repression. Heidegger suggests man creates the world through logos; the verbal construction of place is the dwelling of Being. We live in what we create. Heidegger uses the concept of a bridge to reveal this in-dwelling:

The bridge . . . does not just connect banks that are already there. The banks emerge as banks only as the bridge crosses the stream. The bridge designedly causes them to lie across from each other. One side is set off against the other by the bridge. . . . With the banks, the bridge brings to the stream the one and the other expanse of the landscape lying behind them. It brings stream and bank and land into each other’s neighborhood. The bridge gathers the earth as landscape around the stream.

Consequently, the building of a bridge is a concept in which humanity-dwelling-in-the-world names, describes, and brings into relation its environment. However, Irigaray argues Heidegger forgets from which the bridge, the bank, and the stream are constructed:

Built on the void, the bridge joined two banks that, prior to its construction, were not: the bridge made two banks. And further: the bridge, a solidly established passageway, joins two voids that, prior to its construction, were not: the bridge made the void. How not suspend that toward which it goes, that toward which it returns, in a serene awaiting.

It is the logos, the rational spoken word that first divides the void, the deep, or the chaotic placeless substrate that founds the bridge. Irigaray suggests Western philosophy creates a dwelling at the expense of what cannot be conceptualized. For her, the placeless substrate is fluidity, process, and passage; the dominant metaphor used to concretize the placeless dwelling from which Being lives is air. The air defies boundaries but surrounds and enfolds Being. It is the womb from which life is birthed. Consequently, place is not where boundaries are established, but where boundaries are removed; place is fuzzy. The fluidity of place requires an acceptance of permeability and porosity. Sex and pregnancy provide biological examples of this kind of place:

The fetus is a continuum with the body it is in. . . . It passes from a certain kind of continuity to another through the mediation of fluids: blood, milk. . . .

There are times when the relation of place in the sexual act gives rise to a transgression of the envelop, to a porousness, a perception of the other, a fluidity.

Irigaray reminds us that the bioregion is enfolded by a larger placeless, uninhabited space. Swirling through the trees, passing through my body, and condensing from another dimension, the global commons are the chaotic waters and hovering spirit. The global commons are the ecological unbounded place of cosmology. Later, we will see how this formless space is the beyond-the-horizon location of an imaginal world intersecting the beyond with the line of our perception. For now, I hope to maximize the development of the global commons as the uterus of all bioregions. Global atmosphere and ocean are non-linguistic elements with a fecundity of dwelling spaces. All verbal dwellings, geographical conceptions, and logocentric units are reductions of a larger reality that cannot be named. Whether regions are defined as bioregions or nation-states, these dwellings are already built up from a frothy void. The global commons must be re-mythologized as the primordial elements of water and air. Without a primordial cosmology, uniquely enfleshed in various bioregions, all forms of terrestrial dwelling will be overturned by the primordial froth. Irigaray suggests the need for a relational approach to the primordial in contrast to the logo-centric domination of the void. By remembering the global commons through primordial cosmology, humanity is brought into relation. As society forgets the primordial, the creatures of the deep stir. Stated differently, the extended phenotype of Western globalized culture will wash downstream into the deep where niche construction will quickly precipitate a crash; the Leviathan will play.

The Leviathan and Global Commons

Recently, process theology, chaos theory, and postmodern theopoetics have engaged the rich texts and subtexts of ancient Hebrew primordial myths. For my purposes, I want to focus on the Leviathan text of Job 41. The voice that Job has been goading to speak finally speaks in chapter 41. The voice whistles from a whirlwind. Couched as a deluge of questions, the voice asks if Job is aware of the mythic beast called Leviathan:

No one is so fierce as to dare to stir it up. Who can stand before it? Who can confront it and be safe? . . .When it raises itself up the gods are afraid; at the crashing they are beside themselves. . . . It makes the deep boil like a pot. (Job 41:10–11, 25, 31)

For my purposes, Job is not a book about explaining injustice, but a discursive meditation of losing the mythical cosmology of a world in relation to others. The content of God’s response is cosmological, refusing to explain the meaning of the world according to human interests. The voice of God emanates from the same turbulence that shook the roof down upon Job’s children. When the voice responds, it does not provide answer to the question, “Why me?” Rather, the voice overpowers Job. Strictly speaking, Job experiences an epiphany, or in Catherine Keller and Timothy Beal’s language, a “tehophany.” Job is enveloped into chaos. The voice from the air reminds Job of the multiple intelligences beyond the horizon within the deep. The Leviathan is a personification of chaos and the primordial unbounded tehom of Genesis 1. Both Keller and Beal see the divine voice from the whirling air as an extreme vision of the divine—not as the master of chaos, but within chaos.

The gods are fearful in the face of the Leviathan. The man-made gods of creation ex nihilo, the gods who tower over creation whipping it into submission, cower at the bubbling surface of the deep. These industrial gods who only view creation through domination are surprised at the self-organizing voice that speaks from the deep; the voice—from the whirlwind that synchronizes into syllables, the message that blooms from billions of independent sun-catching organisms, and the face perceived from the steam of the boiling deep—emanates from a primordial place. The untamed Leviathan from primordial space and time is the material which the Spirit of God hovers over in Genesis and the substance of Job’s tehophany. The synchronicity of worldly elements is a kind of “material mysticism” that rips into the industrial world of humanity. Job lives on the surface of reality—as all organisms must do—crying, biting, and retching for survival. Yet, his reality drops into the deep when the voice whistles out of the air. From the same chaotic destruction, a voice of fecundity reseeds a new world. Importantly, the reseeding of new life only begins when Job drowns in a cosmology he does not understand. The violence and oxygenation of the bubbling waters around the Leviathan provide a “chaosmos” that is both self-annihilation and regeneration.

A chaosmos provides a fruitful context for developing a relational perspective to the world. The objectification of the cosmos is a hallmark of industrialization. Broken into non-regenerative pieces, modern civilization takes the face and the voice out of the world. Cosmological personalities provide the structure to hear the voice that emanates out of self-organizing, self-synchronizing sentience. In Job, the dialogue of the Tempter with the Lord undergirds a perception of the universe that suggests chaotic forces are in dialogue. I would suggest Job loses his capacity to hear the primordial voices as his world is destroyed. The majority of the book is a dialogue with non-primordial sentient beings. He rails against the God of heaven to goad God into a response. Unaware of the dialogue in the air, Job is forced to scream back into the atmospheric abyss. When Job passes through the period of waiting, he accepts the possibility of self-annihilation. Though Job is capable of killing God through curse, he refuses to die as an individual-without-relation. When the voice comes, it offers a renewed world-in-relation via the Leviathan. Being in relation to the tehom, Job is both horrified and soothed. The Leviathan is a lover that regenerates through self-annihilation. I will return to the idea of self-annihilation later. At this stage in the paper, I merely want to argue that Job is brought back into relation with the primordial personalities that destroyed his world. In fact, as the story ends, the reader is told that the Lord-of-the-whirlwind regenerates more abundance for Job. The reader leaves Job at a feast in which his friends offer sympathy for the “evil the Lord had done to him.” We can only assume the scars of the event die with Job. Though Job’s friends provide an easy linear causation back to the Lord, the reader is left with a primordial presence that is at once the face of the Tempter, the heavenly Lord, and the Leviathan. What will bubble up from the deep next is impossible to know. But how do ancient primordial characters relate to our modern problems?

Cost/Benefit Analysis and the Global Commons

A relational worldview is the fuel for myth cultivation. The industrial civilization of objectification will not approach sustainable coexistence on earth because sustainability is living in relation to other beings. The relationship with the global commons must be approached through cosmological mythic structures. The Leviathan entices us and horrifies us. But when the world is objectified, perceptual cataracts develop and we lose sight of the face that rises to the surface. Today, environmental policy-making uses cost/benefit analysis, which is based on the idea that complex wholes can be broken into quantifiable parts. Ecosystems and even human life can be counted and fit into a quantifiable economic system. The counting cardinals of modern capitalism demonstrate how blinded industrial society has become to the excess that bubbles out of systems. The excess is part of all holistic systems and a trademark of a chaosmos. Though scientists can count average nutrient overflow from agriculture fields, they cannot count the chaotic relationship nutrients have to a primordial world. We cannot count objects if they are in relation to the primordial. Put differently, we cannot count that which is related to eternity. Cost/benefit analysis is simply a floating island that appears to provide a solid foundation for assessment and risk analysis. Yet the waters are bubbling from the deep on which it floats.

Mundus Imaginalis and the Global Commons

If bioregionalism will offer a more sustainable relationship to the sentience around us, we must develop a mythos beyond regionalism that cultivates relationship to the primordial. From a more philosophical-literary language, the global industrialization of life systems into quantifiable parts represents the objectification of processes, fluidity, and quality. The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard re-mythologized the great global tropes of earth, air, water, and fire. He suggested that an adjective is at the center of the universe not a noun. Objects are merely embodiments of qualities. According to David Miller, a close reader of Bachelard, modern thought forced the substantive into concrete substance. In a move towards quantification, “adjectives came to be absorbed into nouns.” Nevertheless, at the bottom of the world the philosopher does not find a concrete object but a process, a quality, or a dancing spirit that verbalizes and adjectivizes.

Consequently, if we combine Irigaray’s thought with Bachelard’s, the primordial, unbounded, uninhabited nowhere of the global commons is more properly verbalizations and descriptions of a larger life. This life presents a face to humanity. Like Irigaray’s primordial void, we cannot speak of the ocean as a place, but as a process. The oceans and air vibrate relationality into the cosmos. The Leviathan formulates and verbalizes from the deep.

However, Bachelard offers one final nuance of adjectives that will help us connect the global commons to the work of myth-making from diverse bioregions. Bachelard’s concept of verticality refers to a specific function of adjectives that embody epiphany. Key embodiments of verticality in the world provide a relational connection to humanity that both “soars up” and “stretches” down. As Richard Kearney notes, Bachelard’s verticality was a unification of contradictory elements. The stretching of space into a vertical expanse instructively images the connectivity and unfinished relationship of the contradictory elements. This is especially instructive for affirming the global commons as the space of primordial tehophany. Job is both enticed and horrified by the Leviathan. There is feasting and also empathy for the evil done. Laughter and horror provide the epiphanic event when the face of the deep personifies onto the human landscape.

For Bachelard, the coupled contradiction compacted ordinary time, disrupted ordinary thought, and pushed the energy and tension into a verticality of height and depth. He claimed the “epiphanic instant” preeminently occurred in the peculiar adjectival speech of poetry. More specifically, the poetic is a kind of imagination that both induces and is induced by the epiphanic instant. Though Bachelard used the literary poem as the vehicle for the imagination to epiphanize, I do not think it follows that we must isolate poetry and bias the cosmological imagination to one specific literary structure. As an ancient oral form, poetry is rooted in narrative dialogue as rhapsodies such as Homer’s so adequately show. But what is the cosmological imagination? Is human imagination merely an escape from reality?

Henry Corbin and the Mundus Imaginalis

We now approach the organ for the human capacity to image mythic archetype—the capacity of imagination. From such diverse thinkers as anthropologist David Graeber and cultural ecologist David Abram, the imagination is a rich subject for exploring the relationship of human thought and ideation with the environmental embodiment of human perception. However, for my purposes, I will only briefly elucidate the “mundus imaginalis” of Henry Corbin and the Iranian Islamic mystics.

David Miller has provided an insightful connection between Bachelard’s work and the expansive work of the theosopher Henry Corbin vis-à-vis verticality. I will borrow this connection to use the mundus imaginalis as a tool for cultivating a mythic relational posture toward the global commons.

As Corbin notes in a book on Islamic philosophy:

Because it has not had to confront the problems raised by what we call the “historical consciousness,” philosophical thought in Islam moves in two counter yet complementary directions: issuing from the Origin (mabda’), and returning (ma’ad) to the Origin, issue and return both taking place in a vertical dimension. Forms are thought of as being in space rather than in time. Our thinkers perceive the world not as “evolving” in a horizontal and rectilinear direction, but as ascending: the past is not behind us but “beneath our feet.”

The extended phenotype and the ecological niche effects that return to the archetypal center sit more comfortably in a spatial framework than simply a linear evolutionary model. As we dive deeper into the microcosm, we find a shadow of the macrocosm. A scholar of Iranian Islamic mysticism, Corbin aligns verticality with the ancient esoteric traditions of Islamic mysticism that re-imagined Zoroastrian angelology and Platonic/neo-Platonic thought. Ushered into stages of ascent and descent, verticality defines the space where the mundus imaginalis operates. The imaginal world of Corbin and the ancient theosophers is an intermediary space between sensation and intellect. Without reducing the imaginal world into the fictional imaginary, this intermediary space provides the perception of the ecstatic vision. In the imaginal world, Moses hears the voice from the burning bush, Jacob sees a ladder extending into heaven, and Job hears the voice from the whirlwind. An expert on Corbin’s thought, Tom Cheetham explains the imaginal world as giving

access to an intermediate realm of subtle bodies, of real presences, situated between the sensible world and the intelligible. . . . On Corbin’s view all the dualisms of the modern world stem from the loss of the mundus imaginalis: matter is cut off from spirit, sensation from intellection, subject from object, inner from outer, myth from history, the individual from the divine.

Between the dualisms of Western consciousness, a void exists. The dualism either causes the imaginal to be fantasy and imaginary or the imaginal is a kind of faculty for artists who do not really live in reality anyway. For the ancient Persian theosophers, the mundus imaginalis, or the ‘alam al-mithal, was grounded in a complex cosmology that related to a complex progression that ascended to the divine. This cosmology was expressed as verticality. In a non-mythical sense, the mundus imaginalis is the faculty of the poet who perceives the adjective/adverb that embodies the world. The imaginal is the bridge that snaps discrete components into metaphor and provides the face or person of the world. For Corbin, unless the mundus imaginalis has

a cosmology whose schema can include, as does the one that belongs to our traditional philosophers, the plurality of universes in ascensional order, our Imagination will remain unbalanced, its recurrent conjunctions with the will to power will be an endless source of horrors. We will be continually searching for a new discipline of the Imagination, and we will have great difficulty in finding it as long as we persist in seeing in it only a certain way of keeping our distance with regard to what we call the real, and in order to exert an influence on that real.

As Cheetham plainly states, the active Imagination must be seen as a faculty that emanates from beyond the human. Otherwise, the secularization of today will label the active Imagination as fantasy. The space where imaginative perception congeals from sensation and intellection must be from a primordial beyond. For the Persian Islamic mystics, the ‘alam al-mithal originated from the divine. For bioregionalism, I believe we must connect the sense of the divine with the beyond of the horizon, with the uninhabited global commons where the Leviathan plays in excess. The excess that reverberates and re-extends back into the genetic archetype cannot be calculated or quantified but is the emergent voice of the primordial Leviathan.

For Corbin, the mundus imaginalis is not a morally charged faculty. Like the vertical polarity unifying contradiction, the mundus imaginalis constructs the perception in which we are horrified and elated. The active Imagination is the vehicle by which we can hear the voice that whistles from the whirlwind. However, Corbin adamantly argues that without a cosmology that pushes the origin of the imaginal into a supra-consciousness, it will collapse into a one-dimensional secularized world ready to be quantified. For this reason, the tehophanic event signals a moment of decision. The Leviathan threatens to stretch the individual into two. Like Job when the voice emanates from the whirlwind and the deep bubbles forth the Leviathan, we are given a pivotal moment to respond: “On one there is the Death of God and the birth of a Promethean, rapacious, and monstrous Humanity. On the other, Resurrection and the poverty of a life in sympathy with beings.”

The mundus imaginalis is not an Islamic sensibility. Though Corbin stresses the importance of how the imaginal worked with the mystical cosmology of Iranian Sufism, it does not require a Muslim worldview. We may take a final suggestion from Corbin to place the active Imagination into a context in which it can be used by diverse religious traditions including local Christian theologies. Here I quote Corbin’s use of the Iranian philosopher Ibn ‘Arabi:

“Each being,” says Ibn ‘Arabi, “has as his God only his particular Lord, he cannot possibly have the Whole.”

Here we have a kind of kathenotheism verified in the context of a mystic experience; the Divine Being is not fragmented, but wholly present in each instance, individualized in each theophany.

Without allowing a specific religious tradition to dominate the divine, Corbin suggests a traditioned theophany that emanates from the esoteric deep. In this sense, we need people from multiple religious traditions to reach into the primordial stories of their own traditions and the primordial space of the global commons and actively perceive what is bubbling in the face of the deep.

For my purposes, Corbin provides a pliable mysticism that avoids exoteric fundamentalism necessary for a bioregional discipleship. Indeed, Job exemplifies the positive use of the mundus imaginalis when he faces the divine presence that emanates from the primordial air; the book closes with Job resurrected and experiencing a “poverty of life in sympathy with beings.” Job’s friends gather around him in sympathy for the “evil the Lord had done to him.” From the whirlwind that killed his family, Job hears the voice of God. Reconciliation is not achieved by the addition of new barns and children. Rather, Job is brought back into a relationship with the primordial deep. God’s voice whistles from this void, and Job’s ability to hear God from the chaos resituates Job in a world infused with the divine presence. Job’s reconciliation is cosmic and results in sympathy with other beings.

Further, Corbin’s mysticism provides space for valuing the indigenous traditions found in unique watersheds. The simple acknowledgement of religious pluralism does not require a collapse into relativism, but a deeper commitment to the tradition in conversation with a larger global commons ecology. Religious traditions are watersheds which mythologize about the primordial global commons.

Rebirthing Orality: Storied Myth

Over the preceding pages, I have tried to read various scholars to suggest the global commons are the ecological intersection where the divine boils over from primordial void into human imagination. We have a deep-seated fear of and wonder at the primordial fluidity of air and sea. Reading Job, I have suggested the divine voice emanates from the chaotic swirling air (whirlwind) or bubbling deep (Leviathan). Job provides location for ecological epiphany and consequently provides the geography of cosmological Imagination. Analogically, Job’s anthropocentrism is mirrored in the industrialized relationship with creation. As a relationship of dominance and extraction, modern humanity lives alone in a material world devoid of divine presence. In effect for industrial society, the material world swirls around a singular sentience—humanity. Nevertheless, the actions of modern society have profound ecological effects; the primordial deep is stirred. If the industrial human can be characterized as a peculiar composite phenotype, we may wonder how the phenotype is extended into the world. By tracing ecotoxicological results via hindsight, I have symbolized amnesic shellfish poisoning as the result of the extended phenotype of industrial humanity. Consequently, the industrial allele of modern civilization returns from the global commons as amnesia. Different than terrestrial commons, the global commons demand a decentering of human concerns. I believe we will not discover our role as creatures of the earth until we experience the tehophanic event bubbling from the primordial global commons. Until we perceive a larger sentience within the global commons, we will fail to live sustainably in a world of finite resources. Myth gives a face to the resident chaos in the global commons. The mythic traditions woven out of the diverse watersheds can be cosmogonic myths that put industrialized humanity in relationship with the primordial.

As renewed myth, the task must be an oral activism and not a literate conference, publication, or tweet, because the amnesia induced by our global industrial complex is aggravated by literacy dependency. Though literate culture provides incredible resources for the storage of knowledge, it also profoundly affects the social and mental processes of humanity. In particular, literacy objectifies memory, externalizes remembrance, and severs the relational nature of knowledge. For myth-making to provide a social backbone that can foster a bioregional cosmology, the process must be oral.

However, language is not a thing but an event. Language and its discrete words are sounds rooted in bodily gestural speech. In this sense, cosmogonic myths are narrated conversations with both human and more-than-human sentient beings about the beyond-the-human-horizon. These myths are rooted in the oral event of epiphany and refined through social extension. The abstraction and objectification of language onto the page have depersonalized and demythologized the cosmos. As an event, all verbalizations of cosmogonic myth are a singular annunciation that compacts time into a vertical space within the context. The oral myth is not repeated but created anew as it is shared, discussed, and reformatted within the present moment and communal space.

For the ancient Greeks, the act of remembering was itself a mythic returning to the primordial waters. The Muses were the mythic personality of memory and remembrance. To re-member the world, the poet needed help to voice the story. Consequently, though memory was external to the poet, it was personified and required participation with sentience. As Ivan Illich says, “Each utterance was like a piece of driftwood the speaker fished from a river, something cast off in the beyond that had just then washed up onto the beaches of his mind.” These waters were the embodiment of one of the Titans—Mnemosyne; she held all the memories of the dead within her primordial waters. Yet the impact of literacy cemented memory onto the page. Plato had a complicated relationship with writing, and the shift from a primary to secondary orality can be discerned within his writing. For example, in his epistemological work, Theaetetus, Plato uses a literate metaphor to consider how knowledge is remembered. He puts the suggestion in the words of Socrates:

Please assume, then, for the sake of argument, that there is in our souls a block of wax.

. . . Let us, then, say that this is the gift of Mnemosyne (Memory), the mother of the Mousai (Muses), and that whenever we wish to remember anything we see or hear or think of in our own minds, we hold this wax under the perceptions and thoughts and imprint them upon it, just as we make impressions from seal rings. . . .

The participatory nature of knowledge and perception is largely lost when we lose the necessity to ask the Muses for remembrance and concretize knowledge onto the page. Plato begins to technologize memory onto a page within his mind. From such a metaphor, it would seem history inevitably reduced participatory memory onto an external page. Nonetheless, the word is not a sign, but the gesticulated verbalization of the body of the world. The literate conferences Western culture promulgates will be largely uneventful until the oral word is released back into the primordial air and water. Only then will the word become event and usher from the whirlwind. In this light, many indigenous peoples who maintain a tight connection to oral tradition must be at the center of a bioregional activism that will be robust enough to engage with the problems of the global commons.

Conclusion

God-via-Leviathan is in the excess—the overflow and the boiling over of reality. The Leviathan slashes instantly and rips open a verticality that carries us into a tehophany. The moment does not evolve into being but snaps into being. The sentient processes of global systems bubble over in fecundity. From the chaotic deep, billions of sentient beings boil into a primordial bloom. The ecological vertical “epiphanic instant” comes from beyond the horizon, from the deep, and from above. The verticality drives us to imagine as we are stretched along the vertical axis of height and depth. Our toes are driven into the basalt bottoms of the sea while our arms are dragged into the sky abyss. Like a cosmic whirling dervish, the stretched posture opens being to the imaginal world. Only a stretched, cosmic mythology can provide the structure for reconciliation to the Leviathan whose home is beyond the horizon. The Leviathan sleeps in the allelopathic abundance of microbial fecundity. Linear time does not run horizontally, but up and down in a hydrological cycle involving a departure and return—an evaporation and precipitation. As terrestrial inhabitants, we are in relationship to the global commons of air and water. Air and water are substantive verbalizations of the cosmos and not substances we can cut apart and count. Only a relational posture to these global commons will provide a regenerative culture for diverse bioregions.

I believe this excursive investigation provides numerous resources for missiological renewal. First, the divine presence described through Leviathan and whirlwind suggest a wild God that is in relation with sentient beings beyond human. Consequently, reconciliation is a cosmic goal and not simply about human redemption. Humanity is redeemed as creation is redeemed. Further, though God may not be conflated with the Leviathan, God is within the primordial void. As God speaks from the whirlwind and intimately knows the Leviathan, so to be in relation with the global commons is to be in communication with God. Second, the investigation hints toward a kind of mystical missiology that can be ecologically grounded. Often God’s mission is conflated to an anthropocentric soteriology. Like Job, reconciliation resituates humanity within the cosmos. Corbin, Bachelard, and Irigaray provide ways for a more relational posture to the material world and a more accessible ecological mysticism. Through the mundus imaginalis, a postmodern missiology can experience grounded epiphany. This is important for relating the diverse experiences of people and the traditions in which they inhabit. Third, a missional activism should give more attention to contextualized cosmogony. Oral myths which bring society into relation with the primordial provide not only an activism for creation care but foster a sustainable relationship with watershed and local economy.

Kyle Holton worked for nine years in northern Mozambique among the Yao helping initiate a natural resource community center called Malo Ga Kujilana. In 2012 he and his family returned to the States. Kyle is a high school teacher in Little Rock, Arkansas. He has an MA in Intercultural Studies and an MS in Environmental Science.

Bibliography

Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Pantheon Books, 1996.

Ackerman, Frank, and Lisa Heinzerling. Priceless: On Knowing the Price of Everything and the Value of Nothing. New York: New Press, 2004.

Anderson, Donald M., Vera L. Trainer, Joann M. Burkholder, Gabriel A. Vargo, David W. Townsend, J. E. Jack Rensel, Michael L. Parsons, Raphael M. Kudela, Cynthia A. Heil, Christopher J. Gobler, Patricia M. Glibert, and William P. Cochlan. “Harmful Algal Blooms and Eutrophication: Examining Linkages from Selected Coastal Regions of the United States,” Harmful Algae 8, no. 1 (2008): 39–53.

Beal, Timothy. “Mimetic Monsters: The Genesis of Horror in the Face of the Deep.” Postscripts 4, no. 1 (2008): 85–93.

________. Religion and Its Monsters. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Caputo, John D. The Weakness of God: A Theology of the Event. Indiana Series in the Philosophy of Religion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006.

Cheetham, Tom. Green Man, Earth Angel: The Prophetic Tradition and the Battle for the Soul of the World. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2005.

________. The World Turned Inside Out: Henry Corbin and Islamic Mysticism. SUNY Series in Western Esoteric Traditions. Woodstock, Connecticut: First Spring Journal Books, 2003.

Corbin, Henry. History of Islamic Philosophy. London: Kegan Paul International, 1993.

Dawkins, Richard. The Extended Phenotype: The Gene as the Unit of Selection. Oxford: Freeman, 1982.

Faulkner, Joanne. “Amnesia at the Beginning of Time: Irigaray’s Reading of Heidegger in the Forgetting of Air.” Contretemps 2 (May 2001): 124–41, http://sydney.edu.au/contretemps/2may2001/faulkner.pdf.

Graeber, David. Revolutions in Reverse. London: Minor Compositions, 2011.

Hoover, Kelli, Michael Grove, Matthew Gardner, David Hughes, James McNeil, and James Slavicek. “A Gene for an Extended Phenotype.” Science 333, no. 6048 (September 2011): 1401. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/333/6048/1401.abstract.

Illich, Ivan. H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness: Reflections on the Historicity of “Stuff.” Dallas: Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, 1985.

Kearney, Richard. “Bachelard and the Epiphanic Instant.” Philosophy Today 52 Supplement (2008): 38, https://www2.bc.edu/~kearneyr/pdf_articles/pl86279.pdf.

Keller, Catherine. Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming. London: Routledge, 2003.

Laland, Kevin N. “Extending the Extended Phenotype.” Biology and Philosophy 19 (2004): 313–25, http://lalandlab.st-andrews.ac.uk/niche/pdf/Publication84.pdf.

Laland, Kevin N., and Kim Sterelny. “Perspective: Seven Reasons (not) to Neglect Niche Construction.” Evolution 60, no. 9 (September 2006): 1752

Laland, Kevin N., John Odling-Smee, and Sean Myles. “How Culture Shaped the Human Genome: Bringing Genetics and the Human Sciences Together,” Nature 11, no. 2 (February 2010): 137–48. http://nature.com/nrg/journal/v11/n2/abs/nrg2734.html.

Levenson, Jon. Creation and the Persistence of Evil: The Jewish Drama of Divine Omnipotence. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Miller, David. “The Body Is No Body.” In Apophatic Bodies: Negative Theology, Incarnation, and Relationality, Transdisciplinary Theological Colloquia, ed. Chris Boesel and Catherine Keller, 137–46. New York: Fordham University Press, 2010.

Ong, Walter. “Before Textuality: Orality and Interpretation.” Oral Tradition 3, no. 3 (1988): 259–69.

________. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. New Accents. London: Methuen, 1982.

Phillips, Jonathan. “Soils as Extended Composite Phenotypes.” Geoderma 149, no. 1–2 (February 2009): 143–51.

Quilliam, Michael A., and Jeffrey L. C. Wright. “The Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning Mystery.” Analytical Chemistry 61, no. 18 (September 1989): 1053A–60A. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac00193a002.

Stephens, Tim. “Study Documents Marathon Migrations of Sooty Shearwaters.” UC Santa Cruz Currents Online 11, no. 4 (August 2006): http://currents.ucsc.edu/06-07/08-14/shearwaters.asp.

Thayer, Robert L. LifePlace: Bioregional Thought and Practice. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Trabing, Wally. “Seabird Invasion Hits Coastal Homes.” Santa Cruz Sentinel, August 18, 1961. http://santacruzpl.org/history/articles/183.