Churches of Christ exist on every continent and in most countries of the world. But how many congregations are there in the various nations and how many Christians comprise those congregations? Further, what ministries are these churches performing? And how might the answers to these questions impact the church’s strategy for the future? This article seeks to discover the answers to these questions.

Global is a small word with gargantuan dimensions. Any attempt, no matter how earnest, to wrap one’s arms around the global status of Churches of Christ is doomed to fall short. So let us establish some caveats from the beginning. First, this article does not include the status of Churches of Christ in the United States or Canada.

Second, this is, at best, only a partial record of what God continues to do through his people, many of whom will remain unknown by us. Third, though every precaution was taken to insure reliable statistics, the lack of a centralized reporting agency with mandatory reporting requirements makes it almost impossible to discover precise statistics.

Complicating matters even more is the absence of a standard definition of what constitutes a congregation. Is it two people? Four people? Or a minimum of five adults from at least two families who meet regularly for worship and have some form of outreach?

Even if we have accurate records, however, it is no guarantee that the Holy Spirit is present in the numbers. Our statistics cannot contain him. Our best efforts cannot control him. Our scientific analyses cannot measure what he accomplishes. We can only get a sense, as if looking through a mirror darkly, of the size and spiritual maturity of churches around the world. But where this article cites statistics, it does so using the most reliable estimates available and almost always lists their sources.

And here are two more stipulations. This article uses Church of Christ and Churches of Christ, with capitals to distinguish our tradition from other Christian groups who at times refer to themselves as churches of Christ. This article also employs the terms America and American to refer to the United States and its residents, respectfully acknowledging that people in Canada, Mexico, as well as Central and South America are also Americans.

Methodology

This study is based on a 2015 survey of missionaries on the field, correspondence with missionaries and leading national Christians from around the world, and the extensive files I have maintained since the 1960s on the growth of Churches of Christ worldwide. In addition, this article utilizes available literature, including websites and missionary blogs.

This study is divided by continents or large geographical areas such as the South Pacific and the Caribbean. The early work on each continent or area is briefly described, followed by an overview of representative countries on that continent. Next are a brief analysis of the challenges and strengths perceived for the churches there, strategic insights for missions, and, finally, a “Looking Ahead” section, which is my brief personal prognosis for Churches of Christ in that particular part of the world.

Finally, the report ends with a conclusion and a bibliography.

Africa

Africa is a diverse continent with 55 nations and 918 languages spoken by 2,000 people groups. Africa is large, three times the size of the United States, including Alaska, and has a population of 1.2 billion people. It is also receptive to the message of Christ. Researchers at the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, under the direction of missions statistician Todd Johnson, stated: “Africa experienced the greatest religious change of any continent over the twentieth century. . . . In 1910, only 9% of Africa’s population was Christian. By 1970 Africa’s Christian percentage had risen to 38.7%, many of whom were converts . . . in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2010 the Christian percentage was 48.3%, and by 2020 it is expected to reach 49.3%.” African minister Isaac Daye agrees, “Africa is religious. It’s in our genes.”

Churches of Christ have been active in Africa for 120 years. Because of the faithful service of pioneer missionaries and those who followed, and especially because of the sacrifices and ardent work of thousands of faithful African evangelists, Churches of Christ have experienced unusual success in Africa.

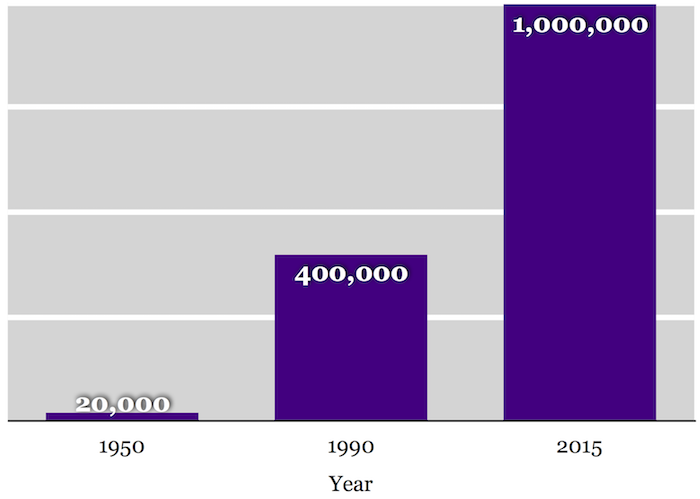

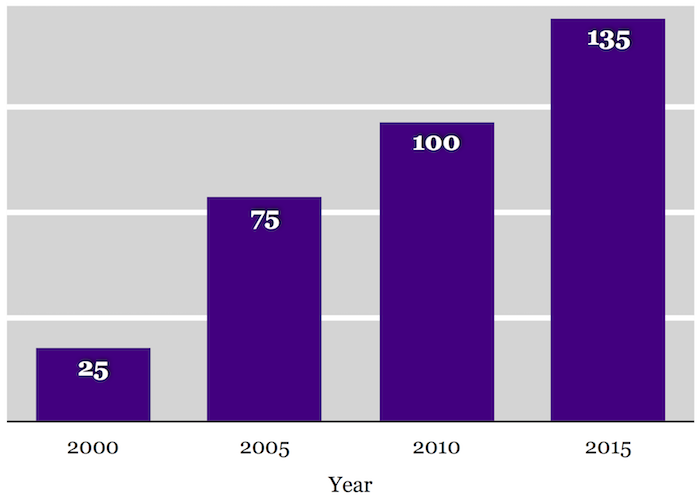

The number of members, as seen in Figure 1, has climbed steeply from about twenty thousand in 1950 to at least one million in 2015. The five countries with the largest church memberships shown in Table 1 represent 82 percent of the total membership in all of Africa.

Figure 1: Membership Growth in African Churches of Christ

Figure 1: Membership Growth in African Churches of Christ

Most of the early missionaries to the African continent through the 1940s settled and served in Southern Africa, which today consists of nearly 7,000 congregations and 350,000 members. Malawi, with 4,100 congregations and 205,000 members in 2002, reportedly had the highest concentration of members per capita (1:80) of any nation in the world.

Table 1: African Nations with the Largest Church of Christ Membership |

Nation | Members |

Nigeria | 322,000 |

Malawi | 205,000 |

Ghana | 100,000 |

Kenya | 80,000 |

Zimbabwe | 76,941 |

Ethiopia | 69,100 |

Total | 783,941 |

Zambia

Churches of Christ began their mission work in Zambia about 1920 when the country was still known as Northern Rhodesia and missionaries started making preaching trips from Zimbabwe across the Zambezi River to Zambia. Early missionaries who moved to Zambia launched mission sites, converted thousands, established numerous congregations throughout the country, and started schools. Most of the leaders in the church and many leaders in the country received their training at these schools.

There were 211 congregations across Zambia in 1990 but that mushroomed to 1,300 churches in 2015. Most of these new churches were planted by Zambian Christians.

South Africa

The situation is markedly different in South Africa, where little church growth has occurred in past decades. A 2002 report showed only 25 congregations and 700 members in the country. The Seiso Street Church of Christ in Pretoria is exceptional because its elders provide strong leadership and have created a climate for evangelism. In a discussion with Sam Shewmaker on April 11, 2016, just days after his return from South Africa, he reported that the Seiso Street church had trained 17 small teams to initiate disciple-making movements in South Africa and had established four new congregations in the last 18 months. Several from the congregation have also made trips to Swaziland to provide leadership training and travel regularly to preach and teach in India.

Kenya

Kenya has been quite receptive to the message of Christ and today hosts 2,000 congregations. During the 1970s and 1980s numerous church planting teams from Churches of Christ were scattered across tribal Kenya. At one point 60 missionaries from Churches of Christ were serving there, more than any other nation.

Gailyn Van Rheenen, who ministered in Kenya among the Kipsigis with his wife, Becky, and their teammates, wrote: “When we left the Kipsigis area of Kenya, where we ministered for thirteen years, there were 100 churches. Today there are 450! This growth has not simply been numerical. These churches have also grown spiritually—using disciple-making and mission to form new communities and growing existing ones.”

One reason the Kipsigis churches continued to grow is because mission teams did not simply plant churches; they nurtured them to maturity. Their model necessitated the church planter role to conform to the maturation stage of the congregation. Roles shifted from evangelist to disciple-maker to leadership equipper and, finally, to guest teacher who exhorts, encourages, and strengthens when visiting. It is a model that can be adapted to rural and tribal areas worldwide as well as to certain urban contexts.

There is a difference between merely starting churches and establishing churches. Churches that are only started often cease to exist within a few years, but churches that are established, that are taken to maturity, generally continue for generations.

North Africa

For security reasons country-specific statistics for this region are not included here, but the aggregate estimates show that there are at least 21 congregations and 716 members in North Africa. Believers in this area often face persecution, imprisonment, or even death if they are found guilty of converting others.

One North African country is home to five congregations and approximately 180 members. An anonymous evangelist there recently reported that over the years he has witnessed more than 1,000 baptisms, but that economics have produced a transient population, making it difficult to keep up with all of the converts.

Challenges for the African Church

Some people believe the doors to Muslim North Africa are closed to Christians. But to those who believe in a powerful God, not all closed doors are really closed. Churches of Christ need to develop creative-access strategies for the resistant nations of North Africa, or as Woodberry suggests, we need to learn how to build bridges over the barriers to these nations.

Another challenge facing the African church is the number of preachers who have a thirst for power. They are fomenting a spirit of bitter division to the detriment of the church. One African said, “Each partisan group belonging to one or the other leader of a congregation” is fighting for control and has created an atmosphere of misunderstanding, discouragement, and even hatred among brothers and sisters in Christ. Commenting on this kind of divisiveness, Erik Tryggestad wrote: “The lack of unity frustrates young preachers, including Nyasulu, who came to Namikango Mission [in Malawi, BW] from the northern city of Rumphi, where he works with a Bible institute. ‘There is lots of division here. . . . I think the main problem is pride and leadership issues.’ ”

Nine years earlier Joy McMillon recorded Samuel Twumasi-Ankrah’s thoughts about the divisions North Americans have exported to Africa: “Teachers from churches of Christ come here and say, ‘Do this or don’t do this, or we won’t fellowship with you.’ They are causing splits within our churches. Give Africans the tools they need for Bible study; train them, but allow them to make their own decisions. The African church should not have to be a reflection of either conservative or liberal churches of Christ in America; we should be a reflection of Christ in Africa.”

These words should not be taken lightly, for Twumasi-Ankrah is the highly respected principal of Heritage Christian College in Accra, Ghana, and the preaching minister for the fourteen hundred-member Nsawam Road Church of Christ in that city.

An additional challenge facing the African church, as well as in many areas of the world, is an unhealthy dependence on financial support from the United States. An extreme example occurred when indigenous preachers in Mali became jealous of the “very good living conditions” of the foreign missionaries and attempted to get rid of them so they could receive their support. When that failed, they tried to sabotage the work, “arguing that if no result is achieved, then the sponsors would terminate their contract with the missionaries.” In this case, the foreign missionaries were Ghanaians, not Americans, sent to Mali by the Nsawam Road church in Accra, who also had set the modest salary of the workers.

Dennis Okoth, the respected principal of Messiah Theological Institute in Mbale, Uganda, gently encourages his African brothers not to become mesmerized by the thought of foreign subsidy. While funding from whatever source can bless Christian ministry, he responds, “I have seen the dignity of many African Christians destroyed when they became dependent on foreign support.” He concludes by saying, “it is time we say ‘no’ to financial arrangements that could be working against us—both the beneficiaries and the donors. We must stand up for the right, even if we stand alone.”

Strengths of the African Church

Sub-Saharan Africa has been more receptive than most other places in the world, and our roots there run deep into history—120 years deep. Likely for these two reasons, we see a more developed infrastructure in Africa than in most other continents. One example is the strong network of schools that train our preachers and church leaders. There are likely more Church of Christ schools, colleges, and universities in Africa than in the rest of the world combined.

There is also an abundance of humanitarian ministries operated by Churches of Christ in Africa. International Health Care Foundation, formerly African Christian Hospitals, facilitates hospitals and clinics in Nigeria, Ghana, and Tanzania. The Indiana-based Malawi Project serves the people of Malawi by providing drought relief, medicines, and medical equipment to hospitals throughout the nation.

Numerous orphanages, especially for children whose parents have died from HIV/AIDS, are active in all parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Healing Hands International (Nashville, TN) serves in many African nations, and around the world, providing clean water, agricultural training, disaster relief, medical care, and other services.

World Bible School (WBS) has played a crucial role in African missions. John Reese, director of WBS, in an e-mail to me on November 24, 2015, wrote: “World Bible School (WBS) has impacted virtually every country on the planet with its Bible correspondence courses and online studies. But nowhere has that been more evident than in Africa. We can easily say that well over 500,000 students are recent or current WBS students in the nation of Zimbabwe, approaching 1 in 20 in that population. Other countries in the top tier of enrollments are Malawi, Nigeria and Ghana.”

Yet another strength in African missions is the strategic international partnerships occurring there, partnerships among equals that are based on mutual respect. One example is the partnership between the elders of the Nsawam Road Church of Christ in Accra, Ghana, and the elders of the North Boulevard Church in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, to send a team of Ghanaian evangelists selected and overseen by the Nsawam Road elders to plant churches in Mali. The first church in Mali was established in 1999 and has increased to nine congregations with more than 200 total members.

In addition, Louisiana-based World Radio sponsors more than 50 daily or weekly broadcasts in Africa. World Christian Broadcasting of Franklin, Tennessee, dedicated in 2016 their station on Madagascar, a large island off the east coast of mainland Africa. Madagascar World Voice programming reaches all of Africa and beyond.

The Africans Claiming Africa (ACA) movement, spearheaded by African Christian leaders and a few missionary counterparts, has been one of the most important watersheds in African missions. ACA began in April 1992 when 160 African church leaders and a few US missionaries met for 10 days to determine the state of the African church and expand their vision for the unfinished task. It was a Day of Pentecost experience for African leaders who were asked to take the lead in African missions. The group has continued to meet every four years.

The evangelistic fervor of everyday Christians is one of the great strengths of the African church. Evangelists in countries like Ghana and Liberia are developing ten-year plans, complete with maps and diagrams, to evangelize their countries. An evangelistic association in Ghana, Africa Mission Network, has set a goal to plant churches throughout French-speaking Africa.

Looking Ahead

Like the team that worked with Gailyn among the Kipsigis, church planting teams have gone to other people groups in Kenya, Tanzania, and a host of other African countries. They and their African converts have developed movements of reproducing churches that now number in the thousands. The dedication and spiritual maturity of these congregations portend a bright future for Churches of Christ in many places across the African continent.

Asia

Asia is home to the world’s largest cities and sixty percent of earth’s inhabitants. Its population is primarily devoted to Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam, while Jesus and the God of the Bible are mostly unknown. Yet Protestant missionaries have been working in Asia for more than three centuries.

Researchers state that East Asia has experienced the greatest Christian growth of any region in Asia. Christian percentages rose from 1.2 percent of the population in 1970 to 8.1 percent in 2010, with projected growth to 10.5 percent by 2020. Much of this growth has been in China—from 0.1 percent of the population in 1970 to 7.3 percent (106 million Christians) in 2010.

Table 2: Average Congregational Size for Asia’s Ten Nations with the Largest Church of Christ Membership |

Nation | Churches | Members | Average Size |

India | 48,880 | 1,139,562 | 23 |

The Philippines | 700 | 40,000 | 57 |

South Korea | 123 | 6,000 | 49 |

Nepal | 600 | 4,800 | 8 |

Thailand | 150 | 2,500 | 17 |

Bangladesh | 90 | 1,750 | 19 |

Indonesia | 51 | 1,651 | 32 |

Japan | 53 | 1,050 | 20 |

Cambodia | 70 | 360 | 5 |

Vietnam | 11 | 350 | 32 |

Totals | 50,728 | 1,197,673 | 26 Avg. |

Israel

Since Christianity began in a Jewish cradle, it was fitting that the first missionary to Asia from Churches of Christ was James T. Barclay, a physician, who was sent with his family by the American Christian Missionary Society to Jerusalem, arriving there on February 10, 1851. Three years later, discouraged by opposition and only 22 converts, Barclay returned to the US, thus ending our early mission to Asia.

Missionaries reentered Israel in 1960, more than 100 years later. They established churches and founded Galilee Christian High School. Joe Shulam, an early convert, planted additional congregations and established Netivyah Bible Instruction Ministry. The Jerusalem Church of Christ is a multicultural congregation of Israeli, Palestinian-Arab, Russian, Armenian, and American backgrounds. The Nazareth congregation, consisting primarily of Palestinian Christians, have had a Palestinian preacher for more than 30 years and ordained elders in 2010, becoming the first congregation in the Middle East to do so.

Cambodia

The first American from Churches of Christ to plant churches in this overwhelmingly Buddhist country was Ted Lindgren, a missionary to Thailand who made periodic trips to northeast Cambodia in the late 1980s.

In 1998 Bob Berard moved to Phnom Penh and asked Bill McDonough, director of Arkansas-based Partners in Progress (PIP) to help him evangelize the country. McDonough said when he visited Cambodia in 2000 there was only one congregation in the country but a world of receptivity. When Bill and Marie-Claire moved to Phnom Penh in 2003, Bill and Berard traveled up the Mekong River to meet a group of 100 Muslims who wanted to study the Bible. “After an all-day class . . . thirty-five went to the river to be baptized.” Less than five months later, Berard was tragically killed in a motorcycle accident.

Humanitarian services provided by PIP played a pivotal role in opening the region to the gospel of Christ. PIP’s Ship of Life, launched in 2006, provides medical care to 120 patients daily along the Mekong River. The ministry also maintains feeding stations in remote villages for 1,200 of Cambodia’s undernourished children.

Ample Bible training is provided by three training schools for preachers. Cambodia Bible Institute in Phnom Penh begun by Bob Berard became a branch school of Sunset International Bible Institute in Lubbock, Texas. Rich and Rhonda Dolan direct the school with assistance from Dennis and Sharon Welch.

In 2008 Bear Valley Bible Institute (Denver, CO) established the International Bible Institute of Siem Reap in Cambodia’s second largest city. The school’s first graduating class was in 2010, consisting of 14 young men and women.

Sokhom Hun and Mike Meirhofer, pulpit minister for the Walnut Hill Church of Christ (Dallas, TX) established Cambodia Bible School on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. Hun, who lost sixteen members of his family to the killing fields of Cambodia, directs the school. In addition to teaching Bible, plans are underway to also train students to support themselves in agriculture or skilled trades such as welding and mechanics. Students and graduates of all three schools engage in preaching and have started more than 40 congregations across the country.

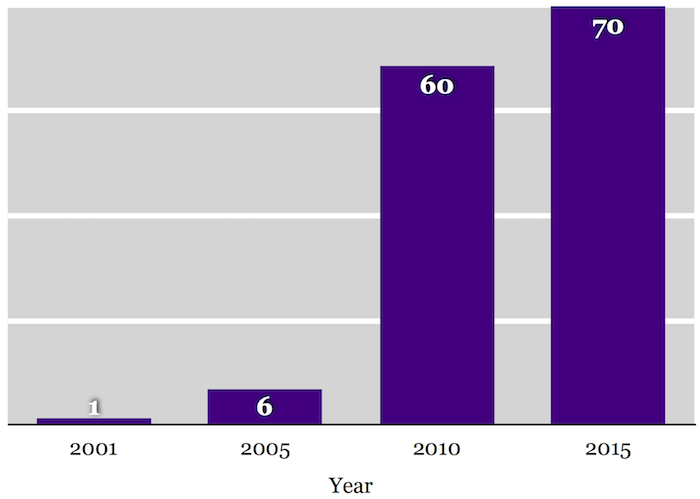

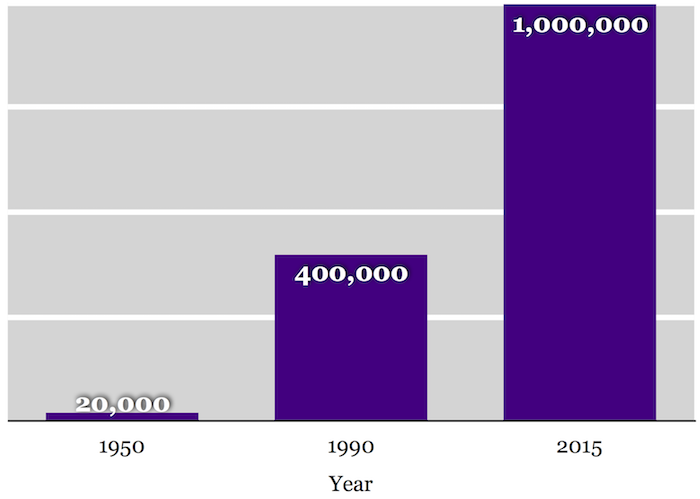

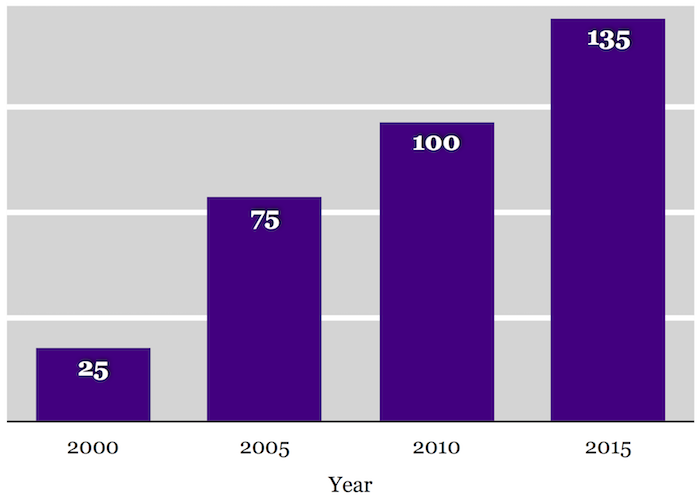

Rich Dolan reported there are seven young churches in Phnom Penh averaging 34 in attendance. Figure 2 shows the increase of congregations from 2001 to 2015.

Figure 2: Growth in Number of Cambodian Congregations

Churches of Christ in Cambodia are relatively young, dating only to 2000 when the first congregation was established, which means that all of the members in Cambodia are first generation Christians. Furthermore, because many congregations in the villages have only 3–20 adult members, they may become discouraged and revert to their former faith unless a network of informal training is initiated.

An approach that may be helpful is Leadership Training by Extension (LTE). This model sends the teachers to the villagers rather than expecting the villagers to come to the teachers. It also reaches the actual church leaders in the villages, always older, experienced people, empowering them to lead effectively. Missionaries in Guatemala in the 1970s had 165 such church leaders in a weekly LTE training program called Hombres Fieles (Faithful Men), based on 2 Timothy 2:2.

Nepal

Nepal, a poor country of 28 million inhabitants, is an example of a country that has never had a full-time trained missionary. Dr. Jerry Golphenee, a self-supported dentist, and his wife Judy moved to Kathmandu in 1996. He recently reported that Nepal had only five congregations in 1987 but now is home to 600 congregations of the Churches of Christ. Golphenee added, “Most of the congregations are small in number and meet in private homes. A large congregation would be around 35. Some may only have three to six members.” Calculating an approximate average of eight members per church would mean that Churches of Christ have roughly 4,800 fellow believers in Nepal.

Bear Valley Bible Institute opened its Nepal Center for Biblical Studies in 2010 with seven men who had been Christians for 3–16 years. The students attend classes during the week and on the weekends they help local congregations by teaching classes, preaching, and helping the churches develop outreach ministries. The Nepal Center is preparing their students to be self-supporting when they graduate and return to their homes. Golphenee has high praise for the school and said: “I have seen more progress, been bothered with less frustration, and have been more encouraged in the last six years than in the previous thirteen years.”

Singapore

The Moulmein Road and Pasir Panjang congregations in Singapore have been bright lights in Asia. Both churches have for many years conducted short-term mission trips to most of Southeast Asia and even to China. In 1990, Pasir Panjang asked veteran missionary Winston Bolt to establish a church on the island of Batam, about a 45-minute ferry ride from Singapore, which he did. The Batam church first met in a small rented building provided by Pasir Panjang. Since then they have baptized over 400 souls, resulting in three congregations on the island.

Bolt established Batam Bible College in 1998 with the goal of planting churches on every island of Indonesia. Since 2000, graduates have planted 60 churches throughout Indonesia, from Batam to Sumatra, to Nias, Java, Borneo (Kalimatan), Sulawesi, and Papua, New Guinea.

In 2010 Missions Resource Network of Bedford, Texas, and the elders at Pasir Panjang formed an official partnership to initiate disciple-making movements that result in strong churches throughout Southeast Asia.

Challenges for the Asian Church

A primary need is to increase the small size of congregations that have already been planted. Churches that consist of only five to twenty members are generally weak and short-lived unless they receive help to grow. Similarly, Churches of Christ need to concentrate their efforts in the 11 Asian countries where we can count fewer than 1,000 members. Having only a few congregations and followers in a country is no indication that our stewardship responsibility has been fulfilled.

Secondarily, churches need to develop innovative strategies for the 15 Asian nations, including the Middle East, where Churches of Christ have no known presence. Considering their borders as closed doors stifles creative thinking and dishonors the Lord.

Islamic terrorists have harassed, persecuted, and martyred Christians in Muslim-dominant nations, making it difficult for them to meet openly. As a result, many have fled to other countries to escape the dangers. Only recently Syria boasted of Christians comprising 20 percent of the population, but today that has shrunk to 7 percent.

Our strategies in Asia have often created a sense of dependency on US finances. Schools, for example, that require full-time enrollment rather than night schools, modular courses, or extension training require funding to cover students’ living expenses. In countries where local churches are unable to provide those expenses, schools turn to the United States for funding. Being on US support throughout their school years, graduates are often programmed to continue on that support as they begin to preach, not realizing that receiving such support may actually hinder their work in the long run.

Strengths of the Asian Church

Today, Churches of Christ are active in more than half of Asia’s 46 countries, from Israel to India and from Pakistan to the Philippines. There are likely more than a million members of Churches of Christ in Asia and more than 50,000 congregations.

Sunset International Bible Institute has fourteen schools of preaching in Asia and Bear Valley Bible Institute International has three. Additionally, there are numerous part-time and full-time Bible colleges, principally in the Philippines and Indonesia. There are also two universities: Korea Christian University in Seoul with 1,500 students and Ibaraki Christian University in Omika, Japan with 2,500 students. Furthermore, World Radio of West Monroe, Louisiana, broadcasts into 13 population groups in Cambodia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Russia, Turkey, and Israel.

There are a variety of humanitarian efforts, from Partners in Progress with their Ship of Life ministering to villages along the Mekong River in Cambodia to MARCH, a Philippine-based medical and disaster relief effort that has ministered to several Asian countries, sometimes aided by doctors from India. There are also numerous orphanages, clean water projects, and feeding programs for undernourished children.

Looking Ahead

The overall health of the church in Asia is reasonably encouraging. Lost people are bowing their knees before the Lord. New communities of faith are being formed. And Christians are being trained for ministry. Former missionary Betty Choate, praising the persecuted Christians in Pakistan where 95 percent of the population is Islamic, said, “Simply standing firm in the faith—and being courageous enough to teach it to others—demands commitment and bravery on the part of every Christian there.”

Despite being persecuted by Islamic terrorists, some Christian Middle Easterners are thankful for ISIS because it is turning Muslims away from Islam and creating in their hearts a hunger for a God of peace. Last year Missions Resource Network led a team on a prayer and survey trip to six nations around the Mediterranean Rim. They heard numerous stories and testimonies of how God is revealing himself to Muslims through dreams and visions, as he did to Cornelius in the first century (Acts 10:1–7).

Europe

Hans Nowak, former German evangelist, wrote, “Europe is the cradle of our civilization, the continent of our heritage,” a kaleidoscope of peoples and cultures. Europe is also the birthplace of the American Restoration Movement, the native land of Thomas Campbell and his son, Alexander. After emigrating to the US, Alexander’s writings about restoring New Testament Christianity made an impact not only in America but also on the family’s native lands of Ireland and Scotland. Readers of his writings established the first Churches of Christ on European soil in the late 1830s. Today there are nearly 12,000 members in 431 European congregations, an average of 28 members per congregation.

Table 3: European Nations with the Largest Church of Christ Membership |

Nation | Members |

Spain | 2,500 |

United Kingdom | 2,500 |

Italy | 2,000 |

Russia | 1,150 |

Total | 8,150 |

For the last 100 years European Christianity has experienced a significant decline in each of its regions except Eastern Europe, a trend likely to continue through 2020. Reasons for this decline include a growing secularism, the deaths of an aging Christian population, and former believers who are turning to agnosticism or atheism.

Researchers say a bright spot is the growth of Independent and Orthodox churches due to Orthodox renewal, especially in Eastern Europe, and migration from the global South, particularly from Africa. They add: “The future of Christianity in Europe will likely be impacted by Christian immigrants, largely from the global South. Included in this trend is the concept of ‘reverse mission,’ where younger churches in the global South are sending missionaries to Europe.”

United Kingdom

When Cline Paden and Paul Sherrod made their exploratory journey to Germany in 1946 they stopped in England on their way. While there, they learned that England had 18 congregations of Churches of Christ with a membership of 453 people. In 1976 the number of congregations in England had grown to 40 with an estimated 1,500 members. By the beginning of 2015, England’s congregations had increased to 49 churches but their total membership had decreased somewhat to 1,332 people.

A steady influx of African Christian émigrés has helped to revitalize churches throughout Europe and especially Great Britain. The Northampton church in England, for example, consists of “Christians from 21 different countries” and has “grown recently both numerically and spiritually.”

On their 1946 stopover, Paden and Sherrod learned there were fourteen Churches of Christ in Scotland with about 450 members. By 1976, six of those congregations had closed, leaving Scotland with eight congregations and some 400 members, but by 2015 that had increased to 26 congregations and 754 members. I know of no congregations in Wales, but there are five in Northern Ireland with a combined membership of 150. Trevor Williams, longtime English preacher, says that in all of the United Kingdom there are 70 churches and 2,500 members, but that some of their older churches are “hanging on by a thread.”

Williams went on to say that like the rest of Western Europe, the UK has changed from being nominally Christian to being multi-faith, citing that there are as many Muslims in the UK as there are members of the Church of England. He described the Churches of Christ in his country as cooperative with one another, financially generous to help when disaster strikes in other countries, and perhaps because of their smaller congregations they experience more family-like fellowship before and after services than what he has seen in America.

Russia

Russia has the largest landmass of any country in the world. Though the country spans both Europe and Asia, we treat it here under the heading of Europe.

Radio broadcasts in the 1960s and 1970s by Polish leaders Henry Ciszeck and Jozef Naumiuk and later by Ukrainian Stephan Bilak helped to encourage an independent movement of some 5,000 believers who were meeting as “churches of Christ” principally in Ukraine but overlapping also into Russia.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991, American Churches of Christ began to flood into Eastern Europe. But after the newness wore off, the flood became a trickle, and today it has been reduced to a drip. Joel Petty says that at one time there were 40 full-time American Church of Christ missionary families serving in Russia. By 2016 only three US missionaries remained, and these are separated from one another by distances of 1,100 to 2,500 miles. That is roughly the equivalent of having one missionary in Los Angeles, one in Dallas and the other in New York City with no other missionaries in between. These lone sentinels of Christ lack frequent interaction with others who share their heart language and culture.

Russia’s approximately 55 Churches of Christ and 1,150 members at the beginning of 2016 have access within the country to several important resources to grow the body of Christ. Christian Resource Center (CRC) in Saint Petersburg offers evangelistic Bible correspondence courses known as Russia Bible School. The CRC also provides leadership training seminars, messages on various topics, and a country-wide newspaper, In Christ, to encourage unity among churches scattered over Russia’s vast area. In addition, the CRC hosts an annual leadership training seminar that rotates between Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and Tomsk, Siberia.

Joel Petty conducts marriage/family and leadership training seminars in various churches across Russia. The Syktyvkar church uses the postal system to edify church members across Russia through correspondence courses on biblical subjects. The Samara and Barnaul churches hold large children’s camps in the summer. Konstantin Zhigulin, a Christian composer, conducts singing schools throughout the country, and the choir of the Neva congregation performs across Russia and Belarus.

Igor Egirev, president of the Christian Resource Center, described the spiritual maturity of the churches: “Overall, churches are learning to take care of themselves after the exodus of missionaries due to bureaucratic obstacles—it became very difficult for the foreign missionaries to remain in Russia for long term [because the government refused to grant visas to missionaries, BW]. Many churches were not ready for that.”

Petty added that some of the churches are in decline, but most are stable and perhaps five are growing. Most of the churches are financially self-supporting, but in a dwindling few congregations support is still received from the US. Petty wrote, “The church on the Neva in Saint Petersburg has a $75,000 annual budget of which 95 percent is funded by contributions of the local church.”

Egirev went on to say:

We are learning to evangelize and plant churches—to be missionaries in our own country. Recently, two new churches have been planted in Siberia. The first congregation is in the Sverdlovsk region and was established by Russian students in the Russian Bible School correspondence program. The second church was planted by Christians from Venezuela who are studying at a University in Vladivostok in the far east of the country on the Sea of Japan and just a few miles above North Korea.

Phil Jackson, Director for European Missions at Missions Resource Network, believes the church in Tomsk, Siberia is the most dynamic Church of Christ congregation in all of Europe. The work in Tomsk began in 1994 and has grown to approximately 120 members, making it one of the largest congregations in Russia.

The Tomsk church works with an orphanage for handicapped children, has built a halfway house for the homeless, teaches the New Life Behavior curriculum, broadcasts a daily radio program, and trains Russian ministers in Tomsk. The church also conducts campaigns to other congregations to encourage and train them in evangelism. Former minister trainees from Tomsk are now serving congregations in several other Russian cities and as missionaries in Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Challenges for the European Church

Churches of Christ, like most of the Christian world, have found Europe to have a low interest in religion. There are of pockets of receptivity, but overall churches grow slowly. Rarely do churches have as many as 100 members. Though Churches of Christ have been in Europe for more than 180 years, there remain 10 countries with no known congregations. There are also 18 European nations that have fewer than five Churches of Christ. Most of these churches are separated from one another by great distances and have less than 15 members apiece.

From a strategic perspective, I believe Churches of Christ should place an emphasis on strengthening the existing congregations and planting new ones in the 18 nations where we already have begun, rather than starting additional small, weak, and eventually dying churches in the 10 “unreached” nations.

We must build a strong base rather than isolated and undermanned outposts. Otherwise, like burning coals separated from the rest are easily extinguished, the countries where we now have fewer than five small congregations will soon follow Finland that once had several small, struggling congregations but today has none. This recommendation is predicated on the slow growth rate or even decline in European churches and the small number of members in those 18 countries.

Strengths of the European Church

Europe has several schools to equip Christians and train prospective preachers. Among them is the British Bible School, established in 1979 at Corby, England, principally to serve the United Kingdom. The Institute of Theology in Zagreb, Croatia, grants degrees in Bible as well as a masters through a partnership with Abilene Christian University. The Institute of Theology and Christian Mission in Saint Petersburg, Russia, uses online training to reach church leaders scattered across that country. The training program in Syktyvkar, Russia, has produced several evangelists. Sunset International Bible Institute has three schools in Europe, one each in Athens, Greece, Bucharest, Romania, and Kiev, Ukraine. Bear Valley Bible Institute has a school in Gorlovka, Ukraine.

Eastern European Mission, based in Texas, has local offices and staffs in Saint Petersburg and Barnaul, Russia, and in Vienna, Austria. They distribute Bibles and biblical literature to churches, public schools and hospitals, prisons, orphanages, and public libraries throughout Russia and other Eastern European countries. They also facilitate children’s camps in Ukraine.

The influx of African Christians has boosted attendance and rejuvenated churches in several European countries. Their faithfulness and lively style of preaching and worshiping, coupled with their zeal for evangelism, continues to bless the church in Europe.

Looking Ahead

Like the immigrants from Africa, the large inflow of Muslim refugees will greatly impact the church in Europe. Fleeing the conflict in the Middle East and North Africa, many are dissatisfied with what they are seeing of an angry and violent Islam. At no other time in their lives will they be more open to the God of love than they will be within the first five years of their arrival.

Refugees from North Africa and the Middle East, because of the love and care they received from Christians at the Omonia Church of Christ in Athens, “want to become disciples of Jesus and one day, take the gospel back to their own people.” Nearly 80 Muslims have already been converted to Christ at the Omonia church. Christians from several European countries will visit Athens this summer to learn from the Omonia church and begin similar outreach efforts to Muslims in other parts of Europe.

If the church does not reach these receptive people today, Islam’s impact will dramatically change the face of European Christianity and the continent of Europe forever.

Reuel Lemmons was a man of unusual vision and wisdom. He wrote in 1984, “We ought to take a good look at Europe. We need congregations in every major city on the continent. We ought to reinforce the missionary army now at work there.” That statement is even truer today. The time is urgent and the opportunities, especially among immigrants, are abundant.

Middle America

Middle America, for the purposes of this article, is that region of Latin America that begins in the north with Mexico (technically a part of North America) and continues to Panama in the South, encompassing the six nations situated between them: Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua.

While the region is still primarily Catholic, 89.8 percent in 1970 and an estimated 83.9 percent by 2020, that figure is expected to continue declining in every country of the region except Mexico. Pentecostal churches throughout Middle America have experienced dramatic growth since 1970, but even more dramatic growth has been experienced by Protestant churches. In some ways, countries like Guatemala, Brazil, and Chile are becoming more Evangelical than Roman Catholic.

Mexico

Churches of Christ from the United States first entered Mexico in 1897–1911 in three failed attempts at establishing evangelistic Christian “colonies” they hoped would expand in widening circles to include Mexican converts. The Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), however, proved their mission was ill-timed.

Four Americans who kept the flame burning for Mexico during the 1930s–1960s include John F. Wolfe, a preacher in El Paso, and three professors at what was then Abilene Christian College in Texas: Howard L. Shug, J. W. Treat, and Haven Miller. These three made numerous trips into Mexico to preach, evangelize, and equip the Christians. Treat recorded Spanish sermons that were made available to any who could use them, including J. R. Jiménez of Cuba who broadcasted them from Havana and Matanzas. Wolfe started Spanish-speaking congregations in El Paso and other places along the Mexican border.

The church in Mexico can trace its roots to about 1932 when Pedro Rivas, a Mexican convert in Texas and schooled at Freed Hardeman College in Tennessee, returned to his homeland and settled in Torreón, where he and others planted a church and established a school to train preachers. From this small beginning, and with the sacrificial work of many Mexican evangelists, a handful of US missionaries, and the financial help of hundreds of North American churches, Mexico now has over 500 congregations and 36,000 believers, the most in all of Latin America.

Churches of Christ in Mexico appear to be strong. There are numerous preacher training schools, including those at Ensenada, Mexicali, and Toluca, all associated with Sunset International Bible Institute (Texas) as well as the school in Torreón. There are also several radio broadcasts, like those of World Radio (Louisiana) in Arcelia and Torreón. And there are children’s homes like the City of Angels in Cozumel and Casa de la Esperanza (House of Hope) in Anahuac, Chihuahua, just 30 miles south of El Paso, Texas.

Guatemala

In 1942, William McDaniel and Howard L. Shug wrote, “Outside of Cuba and Mexico there is not a single established church or missionary of churches of Christ in all Latin-America at the time—nor has there ever been.” That changed in 1959 when four missionary families, including Jerry and Ann Hill and Carl and Edythe James, arrived in Guatemala and started the first congregation.

Local newspapers carried their ads for a Bible correspondence course which proved to be one of the most effective evangelistic tools. Nineteen people responded to the first ad, and the responses increased to the point that in the 1970s missionaries had to limit their advertising to a one-inch ad in the newspaper every two months. Even then the student load outstripped their ability to properly follow up.

Scores of the early congregations began as a result of delivering in person the diplomas and reviewing the final lesson with the students. Occasionally, the students, who generally were heads of households, had already determined to give their lives to Christ before the missionaries arrived with their diplomas.

Churches of Christ multiplied in the fertile soil of Guatemala. At the close of 1977 there were 127 congregations and an estimated 2,400 faithful members of Churches of Christ. Missionaries were forced to leave in 1981 because of civil war. Nevertheless, Churches of Christ continued to grow. Roberto Alvarez, with three respected Christian leaders, reported that by 2015 there were 418 congregations, 33 of them with elders, and 27,000 members following the Lord Jesus.

Figure 3: Guatemalan Church of Christ Growth in Membership

Perhaps the most important decision that led to the amazing growth of the church in Guatemala was the empowering of every Christian to be an evangelist and church planter, rather than reserving that role for only one or two “special” men in a congregation. For the first 30 years, no preacher was supported with funds from the United States. This unleashed the evangelistic power of the entire body of Christ. The church on the La Florida coffee plantation, for example, had more than 20 men who preached somewhere every week. Illiterates memorized passages of Scriptures and brought their friends and families to Christ. Women who sold their wares in marketplaces converted other women working beside them. One sister dedicated a portion of her lot to build a church building and began a new congregation, the first in the country to have elders and deacons, men she had humbly taught and converted.

Health Talents International (HTI) has made important contributions to the growth of the church in Guatemala by following the example of Christ’s dual ministry of proclaiming the gospel and healing the sick. HTI, active in Guatemala since 1973, operates two clinics, one on the coast and another in the highlands, as well as mobile clinics in more remote areas. They train university students in medical missions, have a child sponsorship program, and award scholarships to enable the training of Guatemalans who want to enter the medical field.

World Radio broadcasts throughout the country, reaching even to San Benito, in the far northern jungle area of the Petén, Guatemala’s northernmost department and a difficult place to reach unless one travels by plane. Churches there use the program for their Sunday sermon, and Roberto Alvarez, a preacher in Guatemala City, reports that the Christians “no longer feel alone because of the distance and the remote place where they live.”

The Annual Conferences, held during Holy Week, help to unify the rapidly expanding Churches of Christ. Three to four thousand Christians gather for four days of preaching, teaching, and fellowship. It is an event dear to the hearts of most Guatemalans.

Challenges for the Middle American Church

Churches of Christ in Middle America have primarily reached out to the poor but are now gradually drawing in the middle class. The economic and cultural gaps between these two groups will be difficult to bridge, but applying biblical teaching, loving one another and showing the same respect to rich and poor alike, should foster a bond of unity between the two classes.

A US team of four families from Harding Graduate School pioneered in reaching the Maya Quiché in Guatemala in the 1970s and 1980s, a work that today numbers scores of congregations, many with elders and deacons, and thousands of converts. I know of no other American-led effort by Churches of Christ to evangelize the 21 Mayan groups of Guatemala. The need for this kind of targeted ministry is doubly important because Spanish, the national language, is not the mother tongue of the Maya.

Strengths of the Middle American Church

Churches of Christ in Middle America have been multiplied by converts who are eager to share the good news of Christ. Two Salvadoran evangelists, for example, were the first to plant churches in Nicaragua, a country that has rarely, if ever, experienced full-time American missionaries from Churches of Christ.

Torreón School of Preaching in Mexico and Baxter Institute in Honduras are two of the premier training schools for preachers in Middle America. The Bible Institute of Central America began in 1998 in El Progreso, Honduras, and now has a sister school in Guatemala City.

Latin American Theological Institute in Villa Nueva, Guatemala, eleven miles south of Guatemala City, is an extension school of Bear Valley Bible Institute. Sunset International Bible Institute has associate schools in Ensenada, Mexicali, and Toluca, Mexico; and in Jinotega and Managua, Nicaragua. Texas International Bible Institute has online campuses in La Palma and San Salvador in El Salvador; Guatemala City, Guatemala; and Tegucigalpa, Honduras. World Radio broadcasts in Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua.

In addition to medical care provided by Health Talents in Guatemala, Predisan does the same in Honduras, where they also provide rehab services for addictions. Texas-based Misión Para Cristo works in Nicaragua to deliver health care, feed the hungry, educate the young in the Jinotega and Matagalpa regions of Nicaragua, and provide training for 24 congregations there.

Looking Ahead

Sometimes it is by looking back that we can catch a glimpse of what kinds of blessings the future may hold. In 2002, veteran missionary Dan Coker, who had served first in Guatemala, then in Honduras, Mexico, and Uruguay, wrote these words from Toluca, Mexico:

In 1964, Jerry Hill and I prayed together, asking the Lord to let us see churches of Christ established in all five Central American countries during our lifetime (at that time we only had churches in Guatemala). Recalling that prayer now makes both of us feel very short on vision and faith, because the Lord has done much, much more than we ever dreamed or dared to ask. Now there are many hundreds of congregations with multiple thousands of members in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. And directly or indirectly, I have been privileged to participate in the formative years of those efforts. Thank you Lord!!!!

The future looks bright for Churches of Christ in Middle America.

The Caribbean

Most of the islands in the Caribbean were colonized by European countries from 1492 to the end of the 1700s. Quite a few of the islands are still commonwealths or territories of European nations.

The slave trade from these European nations used the islands to rest their African slaves after the ordeal of their long voyage so they would bring higher prices when sold. The imprints of both the slave trade and colonization are still evident in the Caribbean as most of the inhabitants are of African descent and still speak the language of their colonizers.

Table 4: Caribbean Nations with the Most Churches of Christ and Members |

Nation | Congregations | Members |

Haiti | 200 | 50,000 |

Cuba | 240 | 4,700 |

Dominican Republic | 94 | 3,250 |

Jamaica | 70 | 2,350 |

Puerto Rico | 29 | 1,016 |

TOTALS | 633 | 61,316 |

Roman Catholicism is the largest Christian group in the Caribbean, representing just over 60 percent of the inhabitants and growing at a rate slightly above the general population growth. Researchers indicate that Protestants are “the largest Christian tradition in most English-speaking nations in the Caribbean.”

The best estimates indicate that there are nearly 66,000 members of Churches of Christ in the Caribbean, grouped in 788 congregations, most of which are in the five countries listed in Table 4.

Jamaica

The first known missionary to the Caribbean from the Stone-Campbell movement was Julius Beardslee who was sent to Jamaica in 1858 by the American Christian Missionary Society. He had previously served in Jamaica for 17 years under the auspices of the Congregational Church but became part of the Disciples of Christ during a brief stay in the United States. After returning to Jamaica, Beardslee started planting a church in Kingston and in four years had baptized 172 people.

Churches of Christ had their beginning in Jamaica 100 years later in 1958 when Clifford Edwards invited members of Churches of Christ to visit Jamaica. In 1966–1967, five US missionary families moved to Jamaica. Three years later they opened the Jamaica School of Preaching and in 1980 Jamaican Gladwyn Kiddoe became the school’s director, a post he continued to hold in 2016.

By May 2005, there were 59 Churches of Christ in Jamaica with approximately 2,350 members. By April 2013, the number of churches had increased to about 70. While American churches are still involved in supporting some of the preachers, Jamaicans have accepted full responsibility for the work. There are no known American missionaries in Jamaica today.

Cuba

The first Church of Christ missionaries to enter Cuba were José Ricardo Jiménez and Ernesto Estévez, both of whom were of Cuban descent but born in Florida. Jiménez trained for ministry in the Methodist church, becoming a presbyter in 1928 and that same year he met Estévez, a preacher with the Church of Christ in Tampa. In September 1928, Jiménez was immersed into Christ.

Jiménez arrived in Havana in January 1937 and held services the following Sunday. Almost immediately he began a radio program broadcasted from both Havana and Matanzas to develop contacts in places where he would later plant churches. Over the next three years he launched congregations in the three westernmost provinces of Cuba. Jiménez also bought a printing press and published Revista Cristiana, a Christian magazine, as well as other literature. Estévez arrived in December 1939 and the two of them, working separately in different parts of the island, taught and baptized thousands of Cubans.

At the beginning of Castro’s regime in 1959, Churches of Christ had 100 congregations consisting of some 5,000 believers. They also had six church buildings registered with the government; those registrations would bless them in the tumultuous years ahead. The remainder of the 100 congregations met in homes.

When Castro’s Communist regime banned home meetings and required all Christians to meet only in their registered church buildings, it meant that 94 Churches of Christ were no longer allowed to meet. The government threatened and persecuted Christians, denying them jobs, housing, and civil rights. The regime also banned all religious radio broadcasts and advertising and went so far as to prohibit two of our congregations from singing in worship.

As a result of these hardships, many of the church members, including preachers, left Cuba. Fernández and Archer report that “the majority of the converts, seeing that there could no longer be church services in their towns, joined denominations that had authorized meeting places.” Others, affected by the atheistic stance of the government, abandoned religion altogether. Juan Monroy, a journalist and church leader in Spain, published in his magazine, Restauración, that in 1976 Churches of Christ in Cuba had dwindled to five meeting places, 240 members, and 10 preachers. Figure 4 shows the initial growth of members, followed by the steep decline in 1976 and the dramatic increase in 2005 and 2015. Monroy, speaker for Texas-based Herald of Truth broadcasts, was one of the first contacts from the outside world to visit Cuba and encourage the beleaguered Christians. Taking their lead from Monroy, Christians from America and Canada began arriving to preach and teach.

Figure 4: Variance in Cuban Church of Christ Membership 1946–2015

In the early 1990s, the Cuban government made a momentous change in their stance on religion. Churches were once again allowed to conduct worship services in homes, called casas cultos, and this led to an explosion of meeting places and the doubling of church members.

Between 1995 and 1999, Churches of Christ experienced 5,500 conversions and 52 new congregations inaugurated. The Versalles congregation where Fernández preaches grew from three members in 1992 to more than 700 in 2015 and has planted dozens of other congregations.

Challenges for the Caribbean Church

A possible dark cloud looms over the Caribbean horizon. It is a challenge for both the Cuban and US churches. It concerns how the American Churches of Christ will respond to the opening of Cuba. May God spare the Cuban church from a flood of well-meaning but relationally and culturally insensitive American Christians.

Sometimes Americans believe they know what churches in another country need—even before consulting them. But “good old American know-how” is not what Cuba needs. Or any other country, for that matter, especially in places where the church has persevered for decades.

There is room for partnership, but it must be a partnership between equals. Instead of developing our plans and foisting them on the Cuban church, perhaps we should follow another path that demonstrates greater respect and humility.

What if we showed up not as their superiors or even as their equals, but as their servants? Our question to the most respected church leaders in Cuba would be, “How can we best help you to accomplish your plans for God’s kingdom in Cuba?” We would have no other agenda but that. To listen and to serve. They would be surprised by our humility and demonstration of respect. The result of this approach would mean good news for Cuba.

Strengths of the Caribbean Church

The primary resource for Churches of Christ in the Caribbean basin is the strength of their members, especially in Cuba. These brave men and women have passed through the refiner’s fire of intimidation and persecution, proving their faithfulness. On a nearby island, Jamaican leaders have a vision for the world that reaches beyond the Caribbean even as far away as Nepal, which they impact through translated teaching sessions over the Internet.

Numerous schools are available to nurture Caribbean Churches of Christ. The Jamaica School of Preaching and Biblical Studies in Kingston has initiated an extension program for Cubans. Luís Pedraza, a Cuban who graduated from the Jamaica school, directs the extension program that meets in his home in Santa Clara, Cuba.

Bear Valley Bible Institute operates the International School of Theology in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Also in Haiti is the Center for Biblical Training, located in Cap Haitian, which uses curricula provided by Sunset International Bible Institute. Sunset also has extension schools in Havana, Cuba, and Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Baxter Institute, a ministry training school in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, has also prepared Cubans for ministry.

Radio programs include Herald of Truth broadcasts into Cuba from the Cayman Islands and World Radio broadcasts from dozens of stations in Barbados, St. Kitts and Nevis, Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Trinidad.

Three annual conferences in Cuba, the Men’s Conference, the Women’s Conference, and the Youth Conference, have helped edify and unite the churches throughout the country. The annual Caribbean Lectures, which moves from island to island, does the same for the entire region.

Looking Ahead

Leaders on several islands have taken responsibility for evangelizing much of the Caribbean, but there are still nine major islands or groups of islands that have no known presence of Churches of Christ. Haitian congregations, already fluent in French, could take the lead in planting churches in French-speaking Guadeloupe and Martinique. Other Caribbean churches could reach out to the other islands.

If this happens, the future growth of Churches of Christ in the Caribbean could be promising.

South America

The vast majority of South America is Roman Catholic, but Catholicism is declining throughout the region. Brazil, for example, was 88.6 percent Roman Catholic in 1970 and 77.1 percent Catholic in 2010 and will likely continue decreasing, to 74.6 percent in 2020. Catholicism’s decline has resulted in a decrease of South America’s Christian population from 95.1 percent Christian in 1970 to 91.9 percent in 2010.

Table 5: South American Nations with the Largest Number of Church of Christ Congregations and Members |

Nation | Congregations | Members |

Brazil | 254 | 11,051 |

Guyana | 100 | 4,500 |

Venezuela | 70 | 3,500 |

Ecuador | 480 | 2,700 |

Peru | 26 | 1,276 |

Colombia | 51 | 1,250 |

Totals | 981 | 24,277 |

Protestants in South America are increasing, due largely to a flourishing Pentecostal movement. Researchers cite Brazil as typical of most countries in the region. Protestants in that country have increased from 7.6 percent of the population in 1970 to 16.6 percent in 2010 and 17.6 percent in 2020.

Church of Christ missionaries spent weeks crossing oceans to reach Asia and Africa in the late 1800s but did not risk traveling to South America for another one hundred years. The first missionaries to South America from Churches of Christ were O. S. Boyer and Virgil Smith who went to Pernambuco, Brazil, in 1927. By 1935, they had established 20 Churches of Christ, but stateside congregations did not follow through with funding and the missionaries ultimately left their heritage and joined Pentecostal churches. All of the congregations they had established either adopted Pentecostalism or disappeared altogether.

Brazil

Churches of Christ usually mark their beginnings in Brazil with the arrival in 1956 of Arlie and Alma Smith in São Paulo, South America’s largest city. The Smiths established two churches in São Paulo by 1960, consisting of a total of 45 members, and another congregation in Rio de Janeiro. From that humble beginning the church has grown throughout the nation.

In 1961, a team of 13 families moved to São Paulo and set their focus on planting urban storefront churches and a downtown church which they called a “Jerusalem Church.” Their Jerusalem Church gave birth to the Nove de Julho church, which was formed in 1967 by the merging of three congregations. In 2015 this congregation had more than 200 members and has planted numerous other churches while also serving as a landmark church to the city.

In less than 20 years, the 1961 mission team planted multiple congregations and saw thousands of converts. Former missionaries on that team reported that the radio ministry that led to Bible correspondence courses and home Bible studies was their most effective tool for evangelism. The late 1960s saw another surge in missionary work in Brazil with the forming of an effort called “Operation 68.” Fifteen families moved to Belo Horizonte between 1967 and 1968.

Among the initial works in Belo was the establishing of a downtown church, opening the School of the Bible and purchasing acreage in the hills south of the city for a Bible camp.

At the 1974 Pan-American Lectures, held in Belo Horizonte, the São Paulo and Belo teams presented an impressive idea called “Breakthrough Brazil.” It was a dream to recruit teams for 15 major cities that had not yet been evangelized in Brazil and three neighboring countries. These strategic cities, they prayed, would serve as centers for spreading the gospel to their surrounding areas.

With the encouragement of both teams, Ellis Long moved to the States to begin recruiting additional teams, thus giving wings to the dream. He was later joined by Gary Sorrells, his former teammate on the São Paulo team. When more Hispanic cities were added to the list, the name was changed from Breakthrough Brazil to Continent of Great Cities and Dan Coker, an experienced missionary to Spanish-speaking Latin America, was added to the staff. The ministry changed its name once more in 2012 to Great Cities Missions when it began targeting Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking people outside the South American continent.

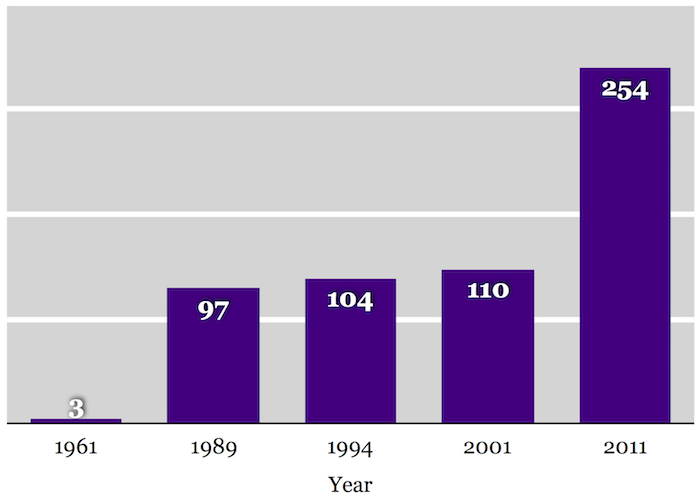

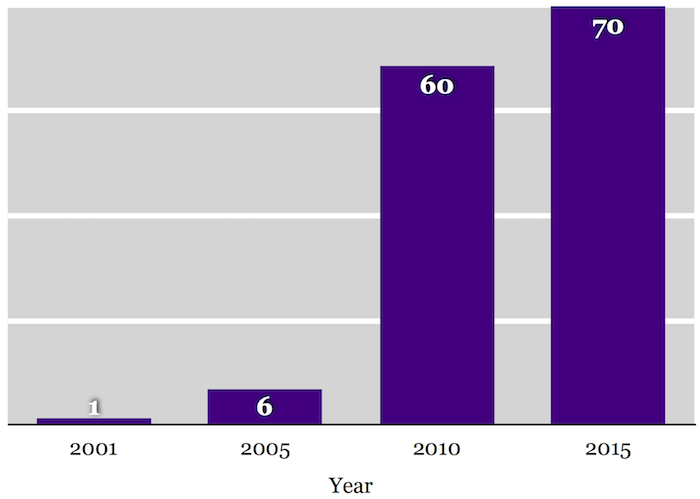

Missionaries and Brazilian Christians teamed to establish new congregations. Figure 5 shows that by 1989 the number of churches grew from three to 97. The growth accelerated between 2001 and 2011, resulting in more than a 100 percent increase during the ten-year period and bringing the church membership to 11,051.

Figure 5: Increase in Number of Church of Christ Congregations in Brazil

Figure 5: Increase in Number of Church of Christ Congregations in Brazil

A primary reason for this growth was that from 1980 to 2009, Great Cities Missions placed 17 mission teams, consisting of 156 missionary personnel, in 14 state capitals of Brazil. They also placed another 12 teams in nine other countries of Latin America. Several of the teams consisted of men and women native to Latin America.

The Nove de Julho congregation in São Paulo was the first to ordain elders, followed in 1993 by the Guarulhos church in Greater São Paulo, and in 1999 by the 300-member Manaus church, located on the banks of the Amazon River, who appointed five elders and seven deacons. By 2015, Churches of Christ in Brazil had ordained elders and deacons in thirteen congregations.

Paraguay

Churches of Christ first entered Paraguay when three Uruguayans held a two-month tent meeting in October and November of 1972. The effort produced no baptisms and follow-up proved unsuccessful, so the trio returned to Uruguay.

In February 1973, the Northside church in Austin, Texas, sent Luís Ramirez from Montevideo to Asunción. Church membership by 1976 was about ten, including seven who had moved from Uruguay to help with the work. From 1974–1982 there were about 30 baptisms, only eight of whom were still faithful by mid-1985.

In January 1981, the Forrest McDonald family, the first of a planned group, arrived in Asunción to work with the church. In May 1983 they began a new work in their home that consisted of their family and one Paraguayan woman. In January 1984, the group began meeting in an office near downtown, and by late 1985 the membership was about 13.

In December 1983, Luís Ramirez, like the McDonalds, began meeting in his home with only one member other than his family. The divisive spirit and unstable marriages of the early Uruguayan evangelists plagued the Paraguayan church for decades.

The first broadcast in Paraguay of the five-minute “La Busqueda” (“The Search”) radio program produced by Herald of Truth was aired in August 1983. The first baptism resulting from the radio program occurred two years later. By July 1985, there were in McDonald’s congregation only three or four male members, two of whom were teaching and preaching. One of the ladies taught the ladies’ Bible class and the children’s Bible class.

The work in Paraguay was difficult and the results were understandably discouraging. After years of unsuccessful pleas for missionaries to join them, the dispirited McDonalds returned to the US in August 1985, leaving no American missionaries in the country.

Eighteen years later, in 2003, a team of missionaries from Freed-Hardeman University, trained also by Great Cities Missions, arrived to plant the Avenida Sacramento congregation. In 2009 it merged with one of the two existing congregations and bought a building.

After seven years spent with the Sacramento congregation and also working with the Centro and Capiata congregations, all of the original team members eventually returned to the United States. They were replaced in 2010 by four new families who arrived to continue the work that was begun at Sacramento Avenue.

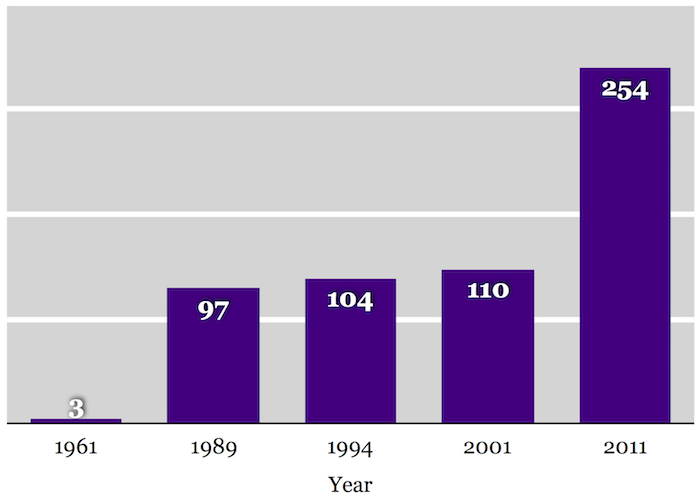

The Sacramento congregation hired a Panamanian missionary in 2013 to work with a new church plant outside the city. Sacramento also partnered with Bear Valley Bible Institute to begin the Asunción Bible Academy, a two-year school to train prospective preachers. The school graduated its first class in February of 2015. Figure 6 shows the steady growth in Paraguayan Church of Christ membership for the years 2000–2015.

Figure 6: Increase of Paraguay Church of Christ Membership

Figure 6: Increase of Paraguay Church of Christ Membership

A second missionary responded to my 2015 survey by saying that the Avenida Sacramento congregation “is close to naming elders, and plans to plant more churches within the next three years.” The team’s labors and God’s blessings over the last five years have resulted in the strengthening of all three churches and an increase of combined church members to 135.

Challenges for the South American Church

Churches of Christ in several South American countries are now comprised of third and fourth generations—generations that often slip into a more relaxed stance with their convictions, resulting in a loss of zeal. Evangelism and new church plants will be needed to maintain a dynamic movement of the future.

Though Churches of Christ have made important beachheads in the federal and state capitals of Brazil and the federal capitals of Hispanic South America, there are still many major cities without any presence of the Church of Christ. There are also hundreds of unreached people groups or tribes in South America that need to hear the gospel of grace and reconciliation. Edward Sewell, who lived in Cuenca, Ecuador, during the 1960s and 1970s, worked among the Quechua, establishing dozens of churches. He was the only missionary known to me who specifically worked with an indigenous South American group.

A Brazilian missionary, in responding to my 2015 survey, commented that the church in most of Brazil is strong, “But the North is almost untouched by the gospel. We need more hardy Christians to take on the challenge of third-world life and separation of great distance to reach the masses of North Brazil.”

Another respondent, this one in Paraguay, wrote that the Sacramento congregation continues to grow, “but there is a great need to plant congregations outside the city. There are only three congregations that we know of in the whole country of 7 million people.”

Strengths of the South American Church

Churches of Christ in South America have strong churches in most of the capital cities of the continent. There are numerous schools and programs throughout the region to train preachers and other Christian workers. Various enrichment conferences are held in several countries, including annual preachers’ meetings, regular training and fellowship events, marriage conferences for couples, and separate retreats for men and for women.

Bible correspondence courses are also accessible, including World Bible School’s Spanish version. An award-winning Christian publishing company, Editora Vida Cristã was founded in São Paulo, Brazil, by Alaor Leite in 1978. It produces Christian literature in both Spanish and Portuguese.

Numerous radio programs are aired throughout the continent. Herald of Truth broadcasts into several Spanish-speaking nations and World Radio is on stations in three Brazilian cities: Campinas, Recife, and Rio de Janeiro, as well as Bucaramanga, Colombia. In addition, there are locally produced radio and television programs in several countries of South America.

Looking Ahead

From the base of strong congregations in the capital cities, a network of churches should continue to spread across the continent. There are already churches with decades of experience and good leadership in many places. Latin American teams have planted churches in neighboring Latin countries. Now they should be encouraged to think beyond their continent. Brazilians, for example, could establish congregations without learning another language in other Portuguese-speaking countries like Angola, Mozambique, and Portugal. South Americans are capable of adapting to other cultures as easily, and in some cases, more easily, than North Americans.

South Pacific

Missionary statisticians note that Christianity in the South Pacific experienced substantial growth in the 60 years between 1910 and 1970. The Christian percentage in 1970 was 92.5 percent of the region’s population, a considerable increase from the 1910 Christian percentage (78.6 percent), “and is indicative of the great success of missionary efforts from many different Christian traditions.” They continue: “Since 1970, however, Christianity’s percentage of the population has been declining in all regions. Two major factors in its decline are (1) secularization, primarily in Australia and New Zealand, which dominate Oceania demographically; and (2) a decrease in conversions from ethnoreligions in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia.”

New Zealand

Churches with the Restoration Movement first entered the South Pacific in 1842 when Thomas Jackson, a Scotsman, arrived in Nelson, New Zealand. He preached undenominational Christianity and established a small church, the first Restoration church in New Zealand.

Table 6: South Pacific Nations with the Largest Number of Churches of Christ and Members |

Nation | Congregations | Members |

Papua New Guinea | 100 | 5,000 |

Australia | 80 | 2,338 |

New Zealand | 25 | 1,700 |

Totals | 205 | 9,038 |

The work in New Zealand was slow until 1865 when growth became more rapid, reaching twenty churches and a total membership of 1,190. By 1903 the numbers had doubled, to 40 churches and 2,446 members. Then growth slowed considerably as the church drifted toward liberal teachings and practices that produced a loss of self-identity and evangelistic fervor.

New Zealand Christians sent out a call for help, which finally arrived in 1955 when E. Paul Mathews moved from California to New Zealand. He and his family settled in Nelson, which became the anchor point for a renewed call to restoration. Mathews journeyed all over New Zealand and began new churches in Invercargill, Tauranga, and Dunedin.

Through Mathews’s recruiting efforts, three more families from California entered the work in 1959 and served with various congregations. Three additional families recruited by Peter Merrick arrived in 1962 and settled at Hamilton, and two of the families helped establish churches in Gisborne and Fiji.

American involvement in New Zealand reached its peak in the late 1960s, when nine families from Sunset School of Preaching joined the work. These families were involved in launching new congregations in Tauranga, Auckland, Napier, and Hastings.

In the 1970s and 1980s a flurry of new churches were begun in Garden City, New Plymouth, Napier, Parklands, Lower Hutt, Hastings, Whangerei, Wainuiomata near Wellington, Auckland’s North Shore, Waipawa, Palmerston North, and Otumoetai, a Tauranga suburb. At the same time, there was a transition from American to New Zealand leadership in evangelism and church growth. To help prepare the church for this change, two schools, both of which are now defunct, were opened to prepare national leaders to assume responsibility for the various churches.

After an exciting start, the churches in Dunedin and other cities slowed down with the departure of the missionaries. Even decades after the missionaries had returned home, many congregations still struggle to survive. “We are trying to discover what makes the adult New Zealand church no longer the offspring of the American church,” said David Steel, who teaches at South Pacific Bible College. Several congregations have failed to make the transition, he added, and have ceased to exist.

The newly established Discover Church in Auckland might serve to revitalize the churches in New Zealand and Australia. It began when a missionary team of three US families arrived in Auckland in 2008. They are having success in communicating the gospel, especially to young adult postmoderns, and have had 18 conversions since 2010, and about 50 people are attending Sunday services.

They believe Discover Church has impacted more than the 200 people whom they can count. Missionary Justin Cherry wrote, “The spiritual climate of our church is vibrant.” He added: “They are eager to learn and even more excited to get into the community together, working alongside each other to share the love of Jesus. They are still young in faith and yet God is raising up potential leaders that have the ability to lead the way into the future.”

Australia

Churches of Christ have a long history in Australia, having been introduced there in 1845 with the arrival from England of Thomas Magarey. The Franklin Street church in Adelaide, which Magarey established three years later, was the first congregation of the movement in Australia.

Growth was exciting, and local churches sprang up throughout the country until the 1920s when, according to McMillon and LaMascus, “the fledgling efforts of local churches were sidetracked by acrimonious debates about issues.” Most of the 136 congregations and 8,000 members chose to ally themselves with other branches of the Restoration Movement, leaving a small remnant of less than 100 members in Churches of Christ.

Between the two world wars, several attempts were made by John Allen Hudson and J. W. Shepherd to renew the work of Churches of Christ in Australia. The task proved to be formidable, with slow progress until the 1950s. After World War II, new interest was sparked in Australia, perhaps in part by our wartime relationship with the people there.

A survey of Australian churches indicates there has been no growth in the number of congregations over the last two decades. While congregations do exist in all of the states and territories, they are quite small. Only two churches have more than 100 members, while 61 churches, 76.3 percent, have less than 35 in attendance, making Churches of Christ in Australia predominantly a “micro-church” movement, meaning that churches are “small enough to meet in a home and unlikely to have a full-time minister or their own meeting place.” With churches so small, it is difficult for them to sustain full-time staff or mount an expensive outreach program.

Both Stephen Randall, an evangelist with the church in Canberra, and Ted Paull, director of the Macquarie School of Biblical Studies in Sydney, have noted how few second generation members of the church there are, and third generation members are extremely rare. Converts and children of converts have fallen away at a precipitous rate.