This article seeks to reflect the reciprocal flow from theology to practice. People of God prayerfully read and discern the meanings of Scripture and are led to Christian practice by the Spirit of God. This flow from theology to practice is illustrated by the theology and practices of missio Dei. The narrative of Scripture describes God as the source of mission. This God, who is both holy and compassionate, calls and sends missionaries who carry out his purposes. These finite humans, however, typically question and doubt their abilities and calling along the journey. The theology of missio Dei implies a number of missional practices: entering God’s presence, interpreting and entering into God’s story, participating in trinitarian community, and incarnating God’s mission. These ministry practices, in turn, give rise to dilemmas and new questions, which lead the practitioner back to theological reflection. Missional growth occurs within this reciprocal interaction between theology and practice.

Theology and Missiology

In a very real sense theology is the mother of missiology. Out of theological reflections we form practical missiological categories and practices. It is equally true that missiology is the mother of theology. Out of missiological practice, we raise questions for theological reflection. These questions deal with how practices reflect the nature and purposes of God. Missions is best accomplished when there is a reciprocal flow from theology to missiology and from missiology to theology. Missiology and theology became distinct disciplines in the Modern Age due to the rise of pragmatism in the West and the need to differentiate teaching specialties within the academy.

When missiology is divorced from theology, practitioners make decisions by their own culturally-derived inclinations. They trust in human ingenuity and assume that they are theologically reflective. Paul Hiebert writes:

Too often we choose a few themes and from these build a simplistic theology rather than look at the profound theological motifs that flow through the whole of Scripture. Equally disturbing to the foundations of mission is the dangerous potential of shifting from God and his work to the emphasis on what we can do for God by our own knowledge and efforts. We become captive to a modern secular worldview in which human control and technique replace divine leading and human obedience as the basis of mission.

Opting into a secular or other non-Christian worldview results in a type of syncretism. Frequently this is an unconscious blending of Christian beliefs and practices with those of the dominant culture. Thus, Christianity speaks with a voice reflective of the culture. Syncretism develops because the Christian community attempts to make its message and life attractive, alluring, and appealing to those outside the fellowship. Over a period of years the accommodations become routinized, integrated into the narrative story of the Christian community, and inseparable from its life.

For example, Jim and his family planted a church. The guiding question forming his strategy was “How can we meet the needs of the people of this community and make this church grow?” Jim raised money for the launch, built a staff, gathered a launch team, held events to gather those interested, held preliminary preview services, and launched a weekly meeting after six months with an attendance of 200 and three years later has an average attendance of 700 people each Sunday. His goal was to launch big in order to develop momentum. By all appearances he is very successful. However, Jim is inwardly perturbed. He acknowledges that his church attracts people because it caters to what they want. The church is more a vendor of goods and services than a community of the kingdom of God. Jim knows that those attending have mixed motives: attending is their duty, a place to meet people of influence, or where children receive moral instruction. Church attendance assuages guilt and declares to others (and to self) that “I am religious.” A spiritual responsibility has been discharged. Therefore, all is well. Observing the disconnectedness and worldliness of members leads Jim to ask himself, “What have I created?”

Developing a theology of missions helps overcome such syncretism.

Metaphors of Theology of Mission

Two “ship” metaphors help us discern this relationship between theology and practice.

A theology of mission is like the rudder of a boat or ship guiding the mission of God and providing its direction. My wife is fond of remembering how our children frequently wanted to “drive” when we took them on pedal-boats. At times they were so intent on pedaling, making the boat move, that the rudder was held in an extreme position, and we went in circles. Realizing their mistake, but still intent on pedaling, they would move the rudder from one extreme to the other so that we zig-zagged across the lake. When missionaries operate without the foundation of a missional theology, their lives and ministries tend to zig-zag from fad to fad, from one theological perspective and related philosophies of ministry to another. A theology of mission, like the rudder of a boat, provides us practical direction for Christian ministry.

A theology of mission is also like the engine of a boat or ship propelling forward the mission of God. One spring my wife and I taught at Abilene Christian University’s campus abroad program in Montevideo, Uruguay. During the semester, we traveled with our students to Iguazu Falls, a spectacular waterfall between Brazil and Argentina. One highlight of our visit was a motorboat excursion against the mighty currents of the river almost to the foot of the falls. I was impressed not only by the immensity of the flow of the water but also the power of the engine to pull the boat against the tide up the river. A mission theology, like the engine of a boat, provides the power that enables finite humans to carry God’s infinite mission against currents of popular cultures.

Jim, in our example, while believing in and preaching from Scripture, unintentionally applied the beliefs and practices of his secular culture to ministry strategy. He believed that human ingenuity employing marketing strategies of a secular culture would grow a church. And in a sense it did! He planted a church with great appeal to the local culture. But it did not reflect the love, holiness, and faithfulness of a people formed to live as participants in the kingdom of God. Jim caught in the ebb and flow of cultural currents inadequately employed the rudder and engine of theology to guide and empower the mission.

A theology of mission provides both direction and empowerment for developing practices of missions.

These metaphors illustrate that theology is indispensable to the mission of God. A theology of mission provides both direction and empowerment for developing practices of missions.

Mission Alive, the church planting ministry with which I minister, encourages participants to move intentionally from Theology to Practices to Structure. We reflect on overarching themes of Scripture like the kingdom of God, incarnation, and missio Dei—threads interwoven in the narrative of Scripture which form Christian reality. We then ask how these themes are practiced within Christian ministry. These theologies and practices guide us to develop spiritually formative structures commensurate with the theologies and practices.

In this article we will consider the theme of missio Dei, the title of this journal and a significant beginning point for discussing the movement from theology to practice.

A Narrative Theology of Missio Dei

This theology, missio Dei, “express[es] the conviction that mission is not the invention, responsibility, or program of human beings, but flows from the character and purposes of God.” God, the source of mission, who is both holy and compassionate, calls and sends his people to be his missionaries who carry out his purposes. As finite humans, however, we typically question and doubt our abilities and calling along the journey.

God, for instance, called Abraham to become the father of an elect nation and sent him to a land that he did not know (Gen 12:1-7). Abraham, however, doubted God’s promises. Why could he not settle in Haran where some of his own people lived rather than going on to Canaan (Gen 11:31)? Would God protect him (Gen 12:10-20)? How could he become a great nation since he had no son (Gen 15:2-6)? What sign would God give him that he would possess the land of Canaan (Gen 15:8-21)? Despite these doubts, Abraham “believed the Lord” (Gen 15:6). His faith grew so that he was willing to obey God’s command to sacrifice his son (Gen 22) because he believed that God, who is faithful to his promises, would raise him from the dead (Heb 11:17, 19).

The biblical narratives of God’s mission invite us to participate. How do these stories describe our lives, provide motivation for ministry, and shape us to become representatives of his mission?

God called the reluctant Moses to go back to Egypt (Exod 3:1-12) to lead the Israelites from captivity. Moses, however, felt inadequate. Forty years earlier Moses, the adopted son of Pharaoh’s daughter, identified the Israelites as “his own people” and felt the injustice of their bondage. He slew an Egyptian slave master (Exod 2:11-15), expecting that they would realize that “God was using him to rescue them” (Acts 7:23). God’s timing, however, was not the same as Moses’. After forty years in Midian, God called Moses to return to Egypt as his missionary of deliverance. Moses feared God’s call. He felt insufficient, afraid that he could not accomplish the task. He failed to realize that the mission was God’s, not his. He was merely the emissary carrying out the mission of God. Moses’ misunderstanding led him to object: “Who am I that I should go?” (Exod 3:11); “Who shall I say sent me?” (Exod 3:13); “What if they don’t believe me?” (Exod. 4:1) and “I have never been eloquent. . . . I am slow of speech” (Exod 4:10). These objections illustrate the human tendency to make God’s mission a mission of self. Each was based on human deficiencies or misunderstandings. God’s responses, however, proclaimed that the mission is greater than the missionary. The ever-present I AM WHO I AM was behind it.

God’s calling and sending is reflected throughout Scripture. He called Isaiah by revealing his holiness, helping Isaiah realize his sinfulness, leading him to repentance and cleansing, and then sending Isaiah to Jerusalem as his spokesman (Isa 6:1-10). God called Jeremiah as a child to prophesy and weep over a disobedient nation (Jer 1:4-8; 8:21-9:2) who were about to go into captivity (Jer 5:18). God called Zerubbabel, Ezra, and Nehemiah at various times and sent them to organize his captive people and lead them back to Jerusalem. God sent his only Son to earth to reveal his “glory, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14), “to seek and to save what was lost” (Luke 19:10), and “to destroy the devil’s work” (1 John 3:8b). Jesus, in turn, sent his disciples, stating, “As the father sent me, I am sending you” (John 20:21, cf. 17:18). Just before Jesus ascended into heaven, God sent his Holy Spirit as another Counselor so that his people would not be left as orphans (John 14:15-18).

The calling and sending of God was also evident in the early Christian church. By his authority as resurrected Lord, Jesus commissioned his disciples to “go and make disciples of all nations” (Matt 28:18-20). These disciples were sent by divine power for divine purposes. God called and sent Peter by the Holy Spirit to the house of Cornelius, thus opening the door to the Gentiles (Acts 10). God called Saul as he was traveling from Jerusalem to Damascus to persecute Christians. In a vision Jesus told him: “I am sending you to the Gentiles to open their eyes and turn them from darkness to light, and from the power of Satan to God, so that they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those who are sanctified by faith in me” (Acts 26:17-18). Paul invited Timothy to join Silas and him as they traveled on the Second Missionary Journey (Acts 16:1-4). Titus accompanied Paul and Barnabas to Jerusalem (Gal 2:1). These early Christians defined themselves as apostles (Rom 1:1, 5; 1 Cor 1:1; cf. Gal 1:15-17) or ambassadors (2 Cor 5:18-20), in other words, those sent to represent God in his mission.

Describe how God has called and sent you as his missionary, that is, one sent by God in his mission for his purpose. What doubts and questions have you felt as a result of God’s calling?

Sometimes God enters into the human situation himself and becomes the Sent One, the Missionary. For instance, when Adam and Eve first sinned, God himself walked in the Garden of Eden seeking his fallen creation (Gen 3:8-19). God fought all night with Jacob, the deceiver who stole his brother’s blessing and birthright, and changed his name to Israel, meaning “one who struggles with God” (Gen 32:22-29). God in Jesus became flesh and entered human culture (John 1:14). God in his Holy Spirit indwells Christians to emancipate them from sin and to lead his people forward in witness to the world (Acts 1:8).

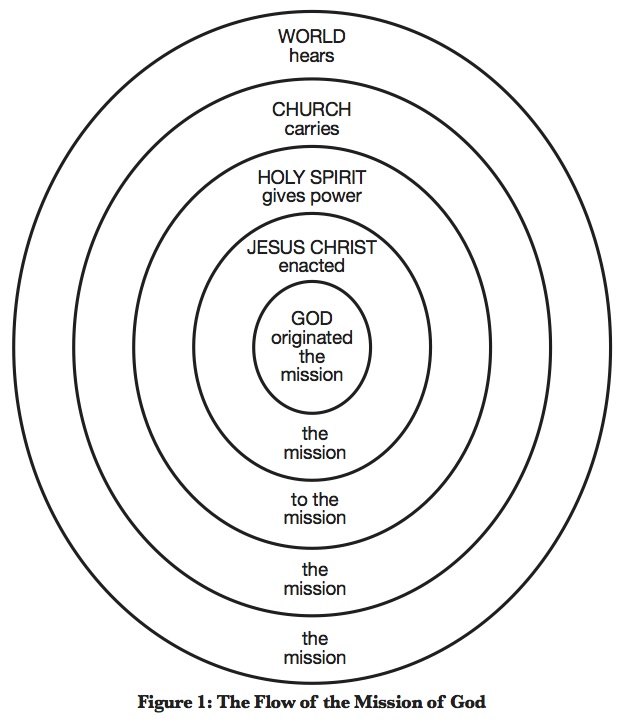

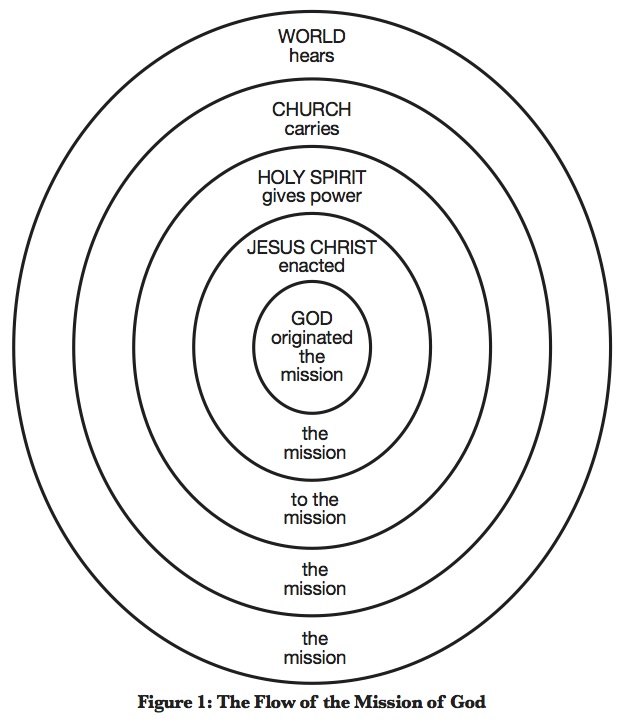

Understanding God’s trinitarian nature amplifies our understanding of missio Dei. God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit, though separate personalities, operate in perfect unity. The church, when living in communion with the Trinity, is called to reflect the harmony and qualities of this union (John 17:20-23). David Bosch describes this trinitarian unity of God’s mission: “The classical doctrine of the missio Dei as God the Father sending the Son, and God the Father and the Son sending the Spirit is expanded to include yet another ‘movement’: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit sending the church into the world.”

God continues to call and send his disciples into his mission, and these disciples continue to question and doubt their calling and ability to fulfill the mission. My wife Becky and I have both received the callings and experienced the doubts. To be frank sometimes I am so filled with insecurity that I question every step I take even as God calls me forward. I have been surprised to find how much I am like Moses, asking God, “Who am I that I should go?” I struggle to listen to God when he says, “I will be with you!”

Early in life I received the call to be a missionary. It was rooted in my upbringing, much like Timothy (2 Tim 1:5), from parental encouragement to experiences in a Christian high school and university to graduate studies. Becky made a decision to be a missionary by marrying one. We felt the hand of God in times of blessing and when Christian leaders spoke into our lives encouraging us as messengers of God. We doubted our ability to leave our parents and friends and form new relationships in another land, to raise our young son (and children to come) in a foreign land, to learn new languages and cultures, and to serve as God’s messengers opening a new area to his gospel. I especially worried because of a learning disability that hinders language learning. But God was faithful in the midst of our doubts and struggles.

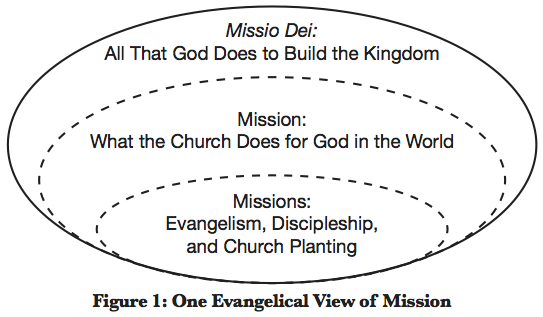

The mission of God, as illustrated in Figure 1, originated in the mind of God. He is its source. The mission flowed from him to Christ, who proclaimed God’s kingdom and in his death enacted God’s kingdom plan. He prayed that the Father would send the Spirit. This Spirit empowered the church for mission. God’s mission flowed, then, from God to Christ to the church, who, empowered by the Spirit, carries the mission to the world. Mission, therefore, is derived from the very nature of God who sends and saves finite humans who doubt and struggle along the journey.

From Theology to Practice

What practices are implied by this theology of missio Dei?

Entering God’s Presence

First, the theology of missio Dei leads us into God’s presence—to be spiritually formed by him. We, as fallen humans, are not magically transformed from sinner to saint. That transformation takes place only as we dwell in God’s presence and allow him to shape us. There are no easy roads to God. The journey is more like navigating the ruts and holes of muddy, rutted roads through forests of obstacles and discouragements than traveling well-paved interstates. Like Abraham and Moses, we question and doubt along the journey, and frequently fall from God. We grow to maturity only by looking beyond ourselves to God. We move into his presence by listening, trusting, depending—moving beyond ourselves to absorb his transforming radiance. Only then are we “transformed into his likeness with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit” (2 Cor 3:18). Spiritual transformation occurs only by God’s power, despite and through our human frailty.

This shaping of our minds and souls is called spiritual formation. Spiritual formation is walking with God in such an intimate way that our character reflects his love, holiness, and faithfulness. Imagine 1 Peter 2:1-3 played out in life: Deborah comes into a Christian community as a spiritually curious God-seeker and “tastes that the Lord is good” (v. 3). While walking with other Christians in community, God begins to mold her in amazing ways, helping her overcome “malice and all deceit, hypocrisy, envy, and slander of every kind” (v. 1). As she comes to Christ a radical transition occurs: “Like a newborn baby, she craves pure spiritual milk, so that by it she grows up in her salvation” (v. 3). It comes from a thirst for living water (John 7:37). God is molding her within a community of Christ-followers, the matrix of her spiritual formation.

This journey of spiritual transformation is an ongoing, threefold process of purgation from sin and the dominion of Satan, illumination of God’s love and holiness, and union with God. These three moves into God’s presence are “simultaneous rather than sequential, but our finitude prevents us from seeing their simultaneity, so that we perceive of them as distinct phases.” The “dryness and fruitlessness” of our souls hinders us from entering the mission of God. Only God can purge, illuminate, and unite us with him. Missio Dei ultimately flows out of this union with God.

Seldom does one enter the presence of God individually; it is typically in communion with others. An African proverb says, “Malale kwendet agenge” (“One piece of firewood alone does not burn”). Thus listening to God almost always implies listening with others on a heart level. One model practiced by many in our church plantings is called CO2, or “Church of 2”. Those on a journey toward God check in with each other to listen to each other as they mutually listen to God. They acknowledge, “Two are better than one, because they have a good return for their work. If one falls down, his friend can help him up” (Eccles 4:9-10). Neil Cole says:

The basic unit of Kingdom life is a follower of Christ in relationship with another follower of Christ. The micro form of church life is a unit of two or three believers in relationship. This is where we must begin to see multiplication occur. Let’s face it: if we can’t multiply a group of two or three, then we should forget about multiplying a group of fifteen to twenty.

In CO2 conversations the acronym SASHET (Sad, Angry, Scared, Happy, Excited, Tender) provides beginning words for describing the condition of the heart. CO2s may be daily phone conversations for two weeks or twice weekly exchanges for a more extended period. A church planter focuses on nurturing a few leaders who in turn nurture other leaders. Church planter Micah Lewis says:

I have found this practice to be the most exciting spiritual practice I have ever done. I don’t even think of it as a practice but simply as pouring myself into a relationship with God. I have started a CO2 with a good friend that I work with at Starbucks. We check in almost everyday [sic], sharing the state of our hearts and talking about how we have been hearing from God. It is really exciting to see how God has been at work in both of us as we listen to him.

An important question is, What spiritually formative practices help sojourners and searchers as well as those of the community of faith come more fully into the presence of God? Practices will vary from culture to culture, context to context. CO2, for instance, is exceptionally appropriate in impersonal, individualistic cultures where people do not naturally walk together.

Imperative to this process is a contemporary catechesis for spiritual formation. This formation process should overview the narrative and fundamental teachings of the Bible; encourage memorization of Scripture (to put nuggets of God into Christian hearts); nurture holiness, love, and faithfulness within the context of ministry; and bring followers face-to-face with significant passages like the Sermon on the Mount. This spiritual formation is not so much taught as caught within a community of nurture, encouragement, and training. Alan Kreider’s The Change of Conversion and the Origin of Christendom overviews the spiritual formation patterns of the early Christian church and illustrates our need to contextualize appropriate patterns with high expectations for those on a journey to kingdom living in this post-Christendom age.

Gradually we begin to listen to God and are surprised that God calls us into his mission. Despite questioning and doubt, we place our lives in his hands and allow him to form and lead us in his mission. Jesus said, “I tell you the truth, the Son can do nothing by himself; he can do only what he sees his Father doing, because whatever the Father does the Son also does” (John 5:19). We likewise acknowledge that we can do nothing by ourselves but only seek to do what the Father does as illustrated by the life and ministry of Jesus.

This transformation leads us to read Scripture in a new and exciting way.

Interpreting and Entering into God’s Story

Second, missio Dei leads us to read Scripture as an amazing story of God’s movement through human history. The Bible begins with the story of creation (“In the beginning, God created . . .”) and the Gospels with the story of Christ (“In the beginning was the Word . . .”). Other genres of Scripture (Law, Letter, Prophetic Oracle, Wisdom, and Psalm, and Hymn) reflect their own particular historical settings.

Many of us, however, learned to think through Modern categories that sought to reduce the Bible to a logical compilation of facts. We assumed that “by avoiding human speculation and confining ourselves to bare scriptural facts, all people could come to understand the Bible alike. The biblical message was simple and clear, needing very little interpretation.” Teachings on salvation focused on steps that we must take to enter the kingdom of God (“hear, believe, repent, confess, and be baptized”) rather than the work of God in bringing us to him. We interpreted the Bible through a hermeneutic of “command, example, or necessary inference” rather than entering into the story of God’s redemptive history and allowing these narratives to form our identity. A new syncretism developed which took the facts of the Bible but interpreted them within the rational grid of our popular culture.

Trevor McIlwain of New Tribes Mission, seeking to understand the pervasive syncretism of the people served by his mission, realized that Christians only partially knew the storyline of Scripture and had inserted Christian components into their traditional narratives. His conclusion awakened me to the need for narrative theology:

We must not teach a set of doctrines divorced from their God-given historical setting, but rather, we must teach the story of the acts of God as He has chosen to reveal Himself in history. People may ignore our set of doctrines as our western philosophy of God, but the story of God’s actions in history cannot be refuted.

The Bible is a narrative describing the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; the Jesus who “appeared in a body, was vindicated by the Spirit, was seen by angels, was preached among the nations, was believed on in the world, was taken up in glory” (1 Tim 3:16); and the Holy Spirit leading his people in mission from Jerusalem to the ends of the earth (Acts 1:8). This trinitarian view of reality is progressively apparent throughout Scripture: the history of missio Dei portrays God the sovereign Lord in the Old Testament, the Anointed One sent to save us in the Gospels, and, in Acts and the Epistles, God’s leading in the church through the Holy Spirit. Bosch’s idea of God sending his Son and Spirit into the world, who in trinitarian unity send the church, becomes increasingly significant for understanding the mission of God. The Bible is a story of God’s sending; a story meant to be told, retold, and told again.

As we read Scripture, we hear within the words our own developing story(ies). Biblical stories focus our hearts, define our reality, and form our allegiance. Lives are shaped by hearing the doubt and faith of Abraham, the spiritual transformation of Jacob, the calling and ministry of Moses, and the gracious hand of the Lord upon Ezra to organize and lead God’s people. We define ourselves within God’s narrative.

Participating in Trinitarian Community

Third, a theology of missio Dei implies community. God, who exists in trinitarian community, calls us to form communities reflecting his kingdom unity. Jesus prayed:

My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. I have given them the glory that you gave me, that they may be one as we are one: I in them and you in me. May they be brought to complete unity to let the world know that you sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me. Father, I want those you have given me to be with me where I am, and to see my glory, the glory you have given me because you loved me before the creation of the world. (John 17:20- 24; emphasis added)

Christ partakes of God’s glory and is thereby united with his Father. A “perichoresis, or interpenetration,” exists “among the persons of the Trinity reveal[ing] that ‘the nature of God is communion.’” The church, when it reflects God’s glory, likewise participates in this unity. The church thus is a “finite” and “temporal echo of the eternal community that God is.” This trinitarian unity, seen in the church, is tangible, readily recognized by the world.

The ancient apologetic of Christianity, consequently, is not merely a set of rational postulates arguing for the existence of God but an incarnational apology of the presence of Christ in his people. “The church is a witness to the presence of Jesus in the world as it embodies and lives out its faith.” As “chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people belonging to God,” we are able to “declare the praises of him who called you out of darkness into his wonderful light” (1 Pet 2:9). Roxburgh and Boren say that the church is called to be “a contrast community shaped by hospitality, radical forgiveness, the breaking down of social and racial barriers, and self-sacrificial love. As we live inside God’s story, we are shaped into habits of life that empower us to be the sign, witness, and foretaste of God’s dream.” The world, as it sees the church serving in its neighborhoods, among its relatives, and in its workplaces, recognizes the church’s distinctiveness. For example, bishops of the early Christian church wrote letters asking Christians not to flee to save their own lives like the Romans when pestilence broke out but to remain to serve the sick.

As a contrast society, the church serves the community by:

- Walking intimately with God, reflecting his love and holiness (2 Cor 3:18)

- Ministering to the poor, sick, and oppressed (Luke 4:18-19)

- Practicing hospitality (Rom 12:13; Lev. 19:33-34)

- Telling the story of God’s kingdom on different levels so that people can contextually hear it (Matt 13)

- Cultivating spiritual friendships (John 4)

- Giving and receiving ministry to help both self and others overcome sin and Satan (Acts 26:17-18)

- Fellowshipping all of God’s people (Gal 3:28)

- Making disciples (Matt 28:19)

These interconnected activities form some of the tangible ministries of a local church and lead the church to develop certain rhythms of Christian life and service.

How these activities are configured into the life of the church is not specifically mapped in Scripture but is learned on the journey. Churches are planted in different ways and with different emphases. Hugh Halter and Matt Smay describe three spheres of an incarnational community: mission, community, and communion. The kingdom becomes tangible in the confluence of these three spheres. Some churches are planted out of mission: what Alan Hirsch calls communitas, or shared ministry. For example, compassionate ministry sometimes leads those serving the poor, sick, and oppressed to define themselves as a church. Some form more slowly out of personal relationship or community, with an emphasis on hospitality and cultivating spiritual friendships. Others form community out of deep communion with God and with each other. The deepness of the church draws sojourners and Christians into the journey with God.

These emphases are reflected within the ministry frameworks of various missional resource people: David Watson of Church Planting Movements emphasizes mission; Hugh Halter and Matt Smay, community; and John White of LK10 Resources, communion. While mission, community, and communion exist in all churches, there are varying emphases.

Developing trinitarian community is a great challenge in church planting and renewal. How does the church grow to reflect this trinitarian unity? The answers are not easy. Primarily, this challenge calls us to live in God’s presence continually being renewed by his Spirit. It involves churches restructuring around complementary gifts rather than hierarchal structures. Attention is given to equipping “God’s people for works of service, so that the body of Christ may be built up” (Eph 4:11-12), to become mature (v. 13). The church thus “grows up into him who is the Head, that is, Christ. From him the whole body, joined and held together by every supporting ligament, grows and builds itself up in love, as each part does its work” (v. 15-16).

Participating in trinitarian community readies the church to participate in God’s mission.

Incarnating God’s Mission

Fourth, missio Dei implies incarnation—that God comes to us and lives in our midst! Sometimes God comes to us personally as he did with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. God incarnated himself in an elect people, the Israelites, so that they might be his light unto the nations, and came to them through prophets and priests. The ultimate expression of God’s incarnation, however, is Jesus Christ. God in Christ became a human being and lived among us so that humans witnessed “the glory of the One and Only, who comes from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). God continues to come to the world through the church, “the continuation of the incarnation . . . the earthed reality of the presence of Jesus in and to the world” and through the apostles, prophets, and evangelists carrying God’s mission to the world.

The ministry of God’s living Messiah provides a model for our incarnational ministry. Even as Jesus taught and served the masses, he focused on equipping and sending disciples. His first priority was making disciples. He modeled, equipped, sent them out, and tutored them when they returned. This equipping prepared many for ministry in what eventually became a church planting movement. Thus the core phrase of the Great Commission—“go and make disciples” (Matt 28:18-20)—also describes the focus of Christ’s ministry.

“Jesus did not come into this world and live His life on a mountaintop isolated from human suffering. He walked among us, ate with us, and shared in our humanity. He did not heal lepers from a distance, but touched them into wholeness. He pressed His disciples and prayed for them to be in the world but not of the world. The focus of their three years together was not the salvation of the Twelve, but their ministry to the entire planet.”

Erwin McManus, Uprising: A Revolution of the Soul (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2003), 111.

This ministry of disciple-making is further defined by Jesus’ words to Saul on the road to Damascus: “I am sending you to [the Gentiles] to open their eyes and turn them from darkness to light, and from the power of Satan to God, so that they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those who are sanctified by faith in me” (Acts 22:17-18). Thus Christ’s mission shows searchers a new kingdom reality (“open their eyes”) and breaks the fetters of sin and Satan (“turn them from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God”). This mission creates a compassionate environment of forgiveness (“so that they may receive forgiveness of sins”), a nurturing community (“a place among those who are sanctified by faith in me”).

The mission of Jesus did not begin with the strong and powerful—within the upper class working downward or the middle class working outward—but with the poor and oppressed. The reading from the scroll of Isaiah in the Gospel of Luke is the climax of events describing Jesus’ ministry: he was led by the Spirit in his baptism (Luke 4:22), defeated Satan in the desert (4:1), and appeared in Galilee (4:14). Then Jesus read:

The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to preach good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to release the oppressed,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.

(Luke 4:18-19; cf. Isa 61:1-2)

These words defined–by God’s Spirit–Luke’s understanding of Christ’s mission!

“The year of the Lord’s favor” is the Year of Jubilee, which occurred every fifty years. At this time all debts were to be cancelled, all slaves released, and all lands restored to their previous owners (Lev 12:10, 38-42). The practices of Jubilee, seldom if ever observed, would now be realized in the ministry of Jesus and his disciples.

Jesus did not minister as a lord or earthly power broker. He came as a servant (Mark 10:45), a shepherd of the flock (John 10:11), and a steward of what God had entrusted him (John 5:19). He did not stand at the top of a pinnacle overseeing an earthly kingdom, but at the forefront of a wedge of people on mission being called and sent to minister within the culture and inviting searchers to listen and participate. At an appropriate time Jesus called these searchers, saying, “Come, follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.” He first chose twelve apostles “that they might be with him and that he might send them out to preach and to have authority to drive out demons” (Mark 3:14-15). He then sent out the twelve and then the seventy two-by-two to find a “worthy person” (Matt 10:11) or “a person of peace” (Luke 10:6) to replicate his mission.

Can these simple disciple-making practices of Jesus be reproduced with contextual adaptations in every tribe, people, or nation in the world?

This incarnational model tends to grow slower during the initial years because the emphasis is on disciple-making rather than gathering a crowd. Frequently, God uses these new disciples to teach others who teach others—resulting in a church planting movement. These churches, simple and with replicable processes of disciple-making, develop the momentum of a spreading virus, like the early church or the church in contemporary China.

Missional leaders create environments for discipleship, not by replicating programs or developing projects but through life-on-life in the context of Christ-formed community. Programs and projects may aid specific facets of spiritual formation but often become a replacement for incarnational living. Life-on-life consists of incarnational living in existing cultural contexts, specifically the family, the neighborhood, the workplace, and Third Places.

Missional leaders create environments for discipleship, not by replicating programs or developing projects but through life-on-life in the context of Christ-formed community.

Family or kinship is the deepest relationship in the world, even in the Euro-American West. It is therefore not surprising that people come to Christ as a result of relatives influencing their own people. My co-worker Fielden Allison made a study of sixteen new churches among the Kipsigis of Kenya. Thirteen of the sixteen (or 81 percent) were started by a relative of one of the new Christians. The message of the Gospel generally flowed through consanguineal kinship ties (that is, related “by blood” rather than “by marriage”), and, as is typical in age-oriented cultures, from older to younger relatives. Sue Salazar brought two of her daughters to one of the first meetings of Christ Journey in Burleson, Texas. One daughter came with her husband and their three children; the other with her live-in boyfriend. This extended family became some of the first leaders of the church. It is important even in the West, where family relationships are waning because of individuality and mobility, for Christians to be God’s missionaries to their families.

Neighborhood is likely the second most important context for missional ministry. Roxburgh and Boren say:

The task of the local church in our present situation is to reenter our neighborhoods, to dwell with and to listen to the narratives and stories of the people. . . . It will be in these kinds of relationships that we will hear all the clues about what the Spirit is calling us to do as the church in that place. But this is not a strategy we take to a context; it is a way of life we cultivate in a place where we belong.

Missional Christians reflect all the practices of a missional church. They bring people together for community; neighborhood events, like a cookout or party in the park. They pray for the sick, welcome newcomers, mobilize resources to help those who have lost their jobs, paint houses, build patios, and welcome people to gather around their tables. They walk intimately with God reflecting his love and holiness and cultivate spiritual friendships. Living missionally in community naturally leads to the planting of neighborhood churches in homes, clubhouses, and storefronts. Roxburgh and Boren write, “We are learning to read Scripture with the eyes of our neighborhood, which reshapes our imagination about the mission of God and allows us to begin seeing Scripture in a new way.”

We must also represent God in both our workplaces and in Third Places. Some develop prayer groups with workmates which opens doors to new families and neighborhoods. Christians with children may visit McDonald’s once a week to interact with other parents as they are together in the play area. Others office at Starbucks or Panera Bread or spend time each week in a local pub specifically to be God’s missional presence in those places. Wherever people gather, we are God’s presence . . . for the sake of the kingdom.

The major function of missional leaders is to equip disciples to represent Jesus among their relatives, where they live, and where they work, thereby developing groups listening to and being shaped by the living word of God. Their ministry is personal and empathetic, focused around hospitality and prayer and compassionate service. Through these practices the kingdom of God becomes tangible.

Dr. Gailyn Van Rheenen served as a church-planting missionary to East Africa for 14 years, taught Missions and Evangelism at Abilene Christian University for 17 ½ years, and is the founder and Facilitator of Church Planting in Mission Alive (http://missionalive.org). His books Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Perspectives (Zondervan), Communicating Christ in Animistic Contexts (William Carey Library), and The Changing Face of World Missions (Baker Academic; authored with Michael Pocock and Doug McConnell) are widely used by both students and practitioners of missions. He has edited Contextualization and Syncretism (William Carey Library, 2006), a compilation of presentations of the Evangelical Missiological Society. His Missiology Homepage (http://missiology.org) provides “resources for missions education” for local church leaders, field missionaries, and teachers of missions.

Bibliography

Allen, C. Leonard. The Cruciform Church: Becoming a Cross-Shaped People in a Secular World. Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 1990.

Allison, Fielden. “The Effects of Kinship on Church Growth in the Kipsigis Churches.” In Church Growth among the Kipsigis of Southwest Kenya. Vol. 4. Unpublished, 1983.

Bosch, David J. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. American Society of Missiology Series 16. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1991.

Cole, Neil. Organic Church: Growing Faith where Life Happens. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2005.

Guder, Darrell L., ed. Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998.

Gunton, Colin E. The Promise of Trinitarian Theology. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1991.

Halter, Hugh, and Matt Smay. The Tangible Kingdom: Creating Incarnational Community. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass: 2008.

Heath, Elaine. The Mystic Way of Evangelism: A Contemplative Vision for Christian Outreach. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

Hiebert, Paul G. “De-theologizing Missiology: A Response.” Trinity World Forum 19 (Fall): 4.

Hirsch, Alan. The Forgotten Ways: Reactivating the Missional Church. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2006.

Hirsch, Alan, and Darryn Altclass. The Forgotten Ways Handbook: A Practical Guide for Developing Missional Churches. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2009.

Hunsberger, George, and Craig Van Gelder. Church between Gospel and Culture: The Emerging Mission in North America. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996.

Kreider, Alan. The Change of Conversion and the Origin of Christendom. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1999.

Lewis, Micah. “CO2 (church of two).” Imagine a Daybreak. http://micahlewis.wordpress.com/2010/02/18/co2-church-of-two/.

Luke 10 Resources. “2-Page CO2 Brochure.” Practice #2 – Listening to Jesus with one (or two) others. http://www.lk10resources.com/practice-2.html.

McIlwain, Trevor and Nancy Everson. Firm Foundations: Creation to Christ. Sanford, FL: New Tribes Mission, 1991.

McManus, Erwin. Uprising: A Revolution of the Soul. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2003.

Murray, Stuart. Church Planting: Laying Foundations. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 2001.

Roxburgh, Alan J., and M. Scott Boren. Introducing the Missional Church: What It Is, Why It Matters, How to Become One. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2009.

Van Rheenen, Gailyn. Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Strategy. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996.

________. “Modern and Postmodern Syncretism in Theology and Missions.” In The Holy Spirit and Mission Dynamics. Evangelical Missiological Society Series 5. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 1997.

Webber, Robert. The Younger Evangelicals. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2002.

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. “Third place.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_place.