Missiologist Janine Paden Morgan explores how the ideological environment of post-war Italy—tense church-state tensions, pressures from Communism, and Roman Catholic xenophobia—shaped the theological and ecclesiological emphases of Church of Christ missionaries from the United States. Through her reading of missionary public newsletters and Italian journal articles, Morgan investigates how opposition by the Roman Catholic Church influenced the identity formation among fledgling Churches of Christ to lasting effect. Although there have been a limited number of descriptive accounts of the events of these years, there has been little serious analysis of what those events mean historically and missiologically. For missiologists, historians of missions, and practitioners alike, the important question of how identity is shaped in a climate of strong opposition can have bearing on how missions is understood and carried out globally today.

My brother’s earliest memory is being fiercely shooed away from the window where he was watching a mob forming to burn down the orphanage where he lived with his parents. The mob was led by the village priest; the children’s home a place of refuge for World War II war orphans. The grievous issue was that “heretical” and “foreign” Protestants had not only established an orphanage but had established it in the stronghold of Roman Catholic papal power, not ten miles from the Vatican. My research explores how the ideological environment of post-war Italy—tense church-state tensions, pressures from Communism, and Roman Catholic xenophobia—shaped the theological and ecclesiological emphases of the planting of the Church of Christ in Italy by American missionaries. Through my reading of missionary public newsletters (principally the Frascati Orphan Home Paper) and Italian Church of Christ journal articles (Il Seme del Regno), I investigate how opposition by the Roman Catholic Church influenced the identity formation among fledgling Churches of Christ to lasting effect.

Since the time of Constantine, Rome has stood at the global center of Western Catholicism, its Papal See committed to exercising religious and political authority over the region, such that in the 1940s, when our story opens, close to one hundred percent of Italians were registered as Roman Catholic. Only in the late nineteenth century did Roman Catholic hegemonic power begin to falter during the Italian Risorgimento, a liberalizing movement that sought to separate church and state. At that time, some Protestant churches—Methodists, Anglicans, Baptists, and the Salvation Army—were accorded legal status. This opening, however, proved brief. Benito Mussolini himself, together with emissaries of Pope Pius XI, signed the Lateran Accords reinstating the Roman Catholic church as the official state religion in 1929. While previously recognized Protestant churches were grandfathered in, new groups seeking legal status found it near impossible and faced increasing pressure to disband under the fascist regime.1

After the war and the fall of fascism, the political landscape in Italy was in turmoil. On the heels of the Truman Doctrine, the Cold War, an ideological fight for the minds of its citizens, was also contested in Italy. On the right, the Democrazia Cristiana (DC) emerged as the largest political party. Determined to incorporate the Lateran Accords into the post-war 1948 Constitution, they were committed to keeping the identity of Italy as Roman Catholic; consequently they viewed “foreign” Protestants as a threat to this goal. Roy Palmer Domenico cites one leader’s observation: “Italy was called by God to a glorious Catholic experiment.”2 Although freedom of worship was eventually guaranteed in the new Constitution, the Roman Catholic Church maintained its special privilege, so much so that to cast aspersions on the pope or Roman Catholicism itself constituted a criminal act.

Fiercely anti-clerical, on the far left in the political landscape were the Muscovite Communists, the Partito Comunista Italiana (PCI), who desired the “via italiana al socialismo” (“the Italian road to socialism”), which they termed a progressive form of democracy. In between these two influential parties lay a plethora of other parties seeking to fill the political vacuum, but this description gives a thumbnail sketch of the main stakeholders when a group of largely West Texan preachers arrived in 1949 on the scene.

Nothing could have been more welcome news to a tired and war-weary people than what a group of young Americans were espousing: a radically different form of Christianity than what they had known in the Roman Catholicism of the day. Twelve American Church of Christ missionaries sailed from New York and arrived in Italy in January 1949, joining Gordon and Ruth Linscott already in place. Three of these missionaries, including my father, Harold Paden, had felt the call to return to Italy to help the land that they had fought to liberate during World War II. Their strategy was (1) “Benevolence”: open a children’s home for war orphans and distribute food and clothing to those utterly devastated from the war;3 and (2) “Preach the Word”: teach the Bible, which would liberate people from oppressive Roman Catholicism and “again establish the Church of Christ on Italian soil” as it once had been established in Paul’s time.4 Prepared by their professors at Abilene Christian College and Pepperdine College to expect an arduous process before there were any converts, they were unprepared for what lay ahead. After their second church service, just three weeks after they arrived in Frascati, Cline Paden, the director of the children’s home and Harold’s older brother, reported:

We have evidently caught the Catholics unawares. . . . Many . . . have told us of announcements being made at all the schools and at Catholic services that no one is permitted to come for Bible study. . . . Sunday morning many of [the priests and nuns] ‘happened’ to be along the road leading from Frascati . . . telling people to turn back. We do not know how many turned back, but over 300 of them came! . . .We too have been caught unawares! The overwhelming response to our invitation for Bible study was not expected. Their pleas for Bibles, the eagerness with which they listen to Biblical discussions and the open defiance to the prevailing ecclesiastic authority has taken us all by surprise.5

In April 1949 the Corriere della Sera, a widely-distributed moderate pro-government newspaper, reported vast Protestant activity around Rome. By August, at the six-month mark, the team had distributed over 5000 packages of clothing, 100 packages of food, and 50 packages of medical supplies. According to Harold Paden, “response to this love” brought over 4,000 Italians to Bible classes, and by October 1949, over 130 people had been baptized into Christ.6

Such an overwhelming reaction did not go unnoticed by the Roman Catholic church and the Italian government led by DC politicians. Local priests began to encourage their communities to resist the Protestant incursion. Early converts were ostracized by their families and lost their jobs; several were physically threatened.7 At an open-air meeting at Monte Compatri, a mob led by the Azione Cattolica processed the Madonna through the streets and began throwing rocks through the windows where a house church met. On that occasion, a young boy had his hand blown off when he accidentally set off a landmine intended for the missionaries’ jeep. Cline Paden reported, “Riots and near riots have greeted the initial efforts in many of these communities where work is now beginning.”8 In November, a hostile throng assailed two jeep-loads of missionaries with clubs and rocks, spitting on them, rocking their jeeps with chants of “We want the Protestants’ bones.”9 A witness to that event, Rodolfo Berdini, later attested how he was “full of anger at this inhuman act” and complained to the Roman Catholic clergy at Castel Gondolfo. The priest answered that these actions were necessary so that the “protestants might be driven out of Italy” which led Berdini to a questioning of his own Roman Catholic faith. Berdini then describes how he went “to meet with the American missionaries who had been stoned before our eyes, and for the first time in my life, I took into my hands a complete Bible! For approximately three months, every day . . . we studied the Bible. . . . They have given us a gift greater, rarer, and more invaluable, than man has ever known—Jesus Christ and His gospel of love.”10

The harassment began to generate national and international media attention. The Settimana del Clero, a newspaper for Roman Catholic clergy, covered debates the missionaries held with Cappuccini monks, which inadvertently resulted in more Bible studies being requested by priests.11 Former priests began to be baptized; seven would eventually become theological leaders in the Churches of Christ.12 Rumors abounded on the one hand that the Protestant missionaries were Communist agents due to many communist-sympathizing converts. The Communist Party (PCI), after an initial look, in their paper, Il Paese, began denouncing the missionaries at best as American imperialists and at worst as agents of the CIA. Time Magazine13 and Life Magazine14 reported on the “beachhead” of Protestantism in Italy.

While the harassment of the missionaries and their converts was mostly confined at the local level, Mario Scelba, the interior minister of the government’s DC party, began to wage a war on Protestant missionaries at the macro level in order to keep Italy firmly Roman Catholic, considering it the glue to Italian core identity.15 Under Scelba’s recommendation, in December of 1949 the Italian government closed the orphanage and sent the boys away; the missionaries were denied visa extensions and threatened with expulsion from Italy. At first reluctant to jeopardize Italo-American relations, the US government finally began cautious involvement largely due to pressure from the Paden brothers’ fellow Texans: Congressmen Tom Connally (chair of the Senate foreign affairs committee), Sam Rayburn (speaker of the House of Representatives), Lyndon Johnson, Omar Burleson, and others.16 The editor of the Frascati Orphan Home Paper, Jimmy Wood, in a special issue dedicated to the closure of the children’s home, included a wire written to President Truman denouncing the action of the Italian government.17 Perhaps the largest concerted letter-writing campaign to Congress by the Churches of Christ occurred in early 1950, protesting the closure. By February 1950, three hundred congressmen were each allegedly receiving a thousand letters a week on the matter. A delegation of Church of Christ ministers and elders traveled to Washington to meet with their congressmen. Jimmy Wood, editor of the FOHP, left the meeting with the assurance that the congressmen stood “solidly behind us in our work.” Wood went on to write: “[I] want to assure each of you that your letters have done good.”18 The Americans were given a one-year extension and the children’s home reopened.

During the 1950s the legal battle for freedom of religion in Italy continued and was reported in dozens of newspaper articles. While Scelba backed down briefly regarding the American missionaries, he was vigilantly opposed to Italian evangelists. Services were banned. Churches of Christ in Rome, Veletri, Livorno, Florence, and Alessandria were raided by police and closed. Italian and American evangelists were arrested and given sentences for preaching. When Scelba succeeded as Prime Minister in 1954, his government expelled those “obstinate violators of Italian law,” with his sights firmly set on the gadfly, Cline Paden, the most outspoken and combative of the American missionaries.19 But the battle against the Protestants was not won. Although deported, Paden had found allies in Italy’s judiciary and initiated counter legal defense proceedings for other evangelists as well. The new Constitutional Court inaugurated in 1956 ruled that “government sanction was unnecessary for the establishment of churches in Italy.”20 While there was still action against Italian evangelists throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, courts continually acquitted the Protestants.

As to the ministry of the Churches of Christ in Italy in the 1950s, the Brownwood Church of Christ eldership closed down the Frascati Orphan Home in 1957, deeming it unsustainable due to decline of American financial support and the Italian government’s continued legal obstructions. The rationale was framed as a “redirection of efforts in Italy,” not as a withdrawal from the work there,21 though this move essentially extinguished the “benevolence” prong of the American missionary strategy. However, such “redirection” bore fruit for the second prong, “preach the word.” By the end of the 1950s, twenty-three Italian evangelists, along with a dozen American missionaries, established forty Churches of Christ communities in the principal cities of Italy. A publishing house widely distributed Bible correspondence courses, a monthly journal titled Il Seme del Regno, along with numerous doctrinal pamphlets all in Italian. A Bible school in Milan was begun, its director a former Catholic seminary theologian, Fausto Salvoni. While it was a decade of great oppression, it was also a decade of great activity that is the focus of this study. This history provides context for my research.

Research and Findings

Based on the historical context and ideological environment of post-war Italy, I postulate that if identity is forged in such a hostile environment, the tendency is to define oneself in relation to the “enemy” and not in relation to the central themes of the gospel. In his study of Latin American Protestantism in the early twentieth century, Mexican scholar Carlos Mondragón notes that consistent interaction with majoritarian (and often hostile) Roman Catholic ecclesial and cultural apparati resulted in Protestant identities characterized by reaction to that antagonism.22 This seems to bear truth also to the mid-twentieth-century Italian context as well. In this paper I explore how early Italian converts of the Churches of Christ conceived of their religious identity vis-à-vis the dominant Roman Catholic Church in order to understand its imprint on the Churches of Christ in Italy today. To do so, I have examined missionary public newsletters and Italian journal articles during a ten-year period in order to ascertain what foundational messages the Italian converts received from the American missionaries and what they in turn promulgated.23

Research Question #1: What foundational messages did Italian Church of Christ converts and leaders receive from the American missionaries and then themselves promulgate?

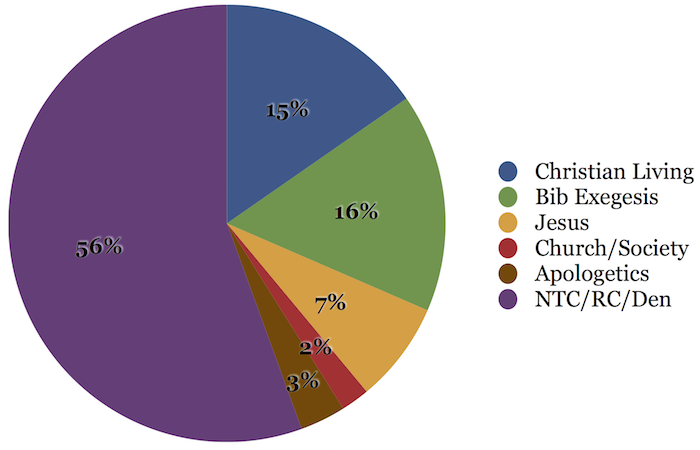

The data in Figure 1 reveals that the primary focus of articles in this ten-year period was what it means to be the New Testament Church (NTC) in relation to Roman Catholicism (RC) and to other Christian denominations (Den).

Figure 1: Topics of Seme del Regno Articles (1954–1963)

Over half of the articles in this time period, fifty-six percent to be exact, were devoted to polemical arguments related to what was considered the New Testament Church versus the Roman Catholic Church. Fifteen percent focused on Christian living, while only seven percent of the articles focused on the person of Jesus.

According to the SdR articles, biblical authority was the only basis on which one can study and know the difference between divine will and human invention. In addition to the New Testament Church (NTC) category, another sixteen percent of the articles focused on exegesis of various biblical texts, showing the primacy of the Bible in its arguments. Any given article I tallied in its first four months gave, on average, twelve biblical references. Such a high view of the Bible and high view of human ability to study it and know “the truth” is a hallmark of Churches of Christ. This proved consistent not only with what the earlier cited Berdini reflected but also with an interview I had with Marisa Sala in 2016. When I asked her about what attracted her to the Churches of Christ in the 1950s, Marisa recounted that for the first time in her life she held a Bible in her hands when a young preacher came to her family’s home. That in itself was astounding for that time. But what really moved her was when, upon reading a Bible passage together, that young preacher, Joe Gibbs, asked her what she understood by it. Sixty years later, Marisa was so moved remembering that moment, she was speechless.24 That she, a young girl, could have something of value to contribute was simply unheard of. Such a freedom for individuals to search for truth, free from human traditions to seek anew, caused the contemporary historian Nathan Hatch to say about the early Restorationists: “Protestants had always argued for sola Scriptura, but this kind of radical individualism set the Bible against the entire history of biblical interpretation.”25 Hughes and Hatch suggest that in so demanding a theology of the people and by the people, they contributed to a democratization of Christianity that had been mired in the professional hierarchies of national churches for centuries.

In the opening editorial for SdR, Corrazza announced that the purpose of the journal is “not to engage in polemics nor to combat any religious community,” but rather begins with “a sincere conviction that Christ is the only source of Christianity, who brings light where there is darkness, love where hate dominates, . . . faith in Christ where there was once idolatry and superstition.”26 In a later article that same year entitled “Return to Jerusalem,” referencing Luke 2:44–45, he used the metaphor of a “little caravan of Christianity that had lost its way from Jerusalem for 2000 years” that had gotten fat, loud, and misdirected. “We have looked inside each cart, but we haven’t found Jesus, the Master.”27 However, we see from the data in Figure 1 that the emphasis was not so much on Jesus, the Master, but what it means to be a New Testament church. And that brings its own polemics.

Research Question #2: How were the claims made to engage the Italian reader vis-à-vis the Roman Catholic Church?

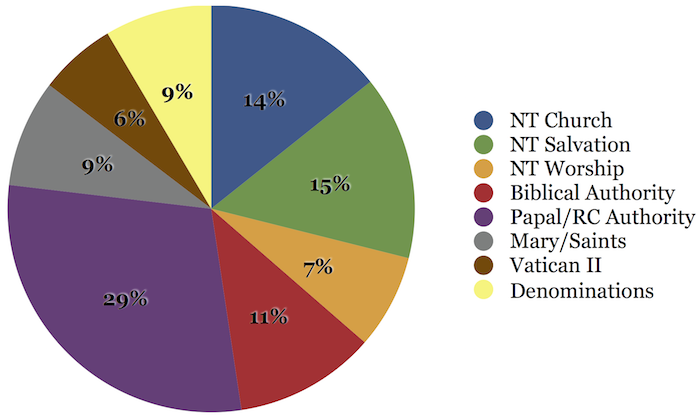

The following figure shows the points of discussion, breaking down the data from the Figure 1 focus labeled “NTC/RC/Den.”

Figure 2: Topical Arguments

The data suggests that the dominating topics were the authority of the Roman Catholic Church (pope and church councils), with New Testament salvation (nineteen out of the forty-three articles were on New Testament baptism) and New Testament church given almost equal treatment, and biblical authority. A letter was written complaining that there was too much argumentation and polemics in the journal, creating “an obstacle to the calm meditation [of Scripture].”28 Corazza agreed wholeheartedly with the writer, stating that he wished to banish every polemic and drink from “the pure fountain of Christian teaching!” However, he goes on to say, “But unfortunately it is necessary to speak out and not remain silent because doing so would be an obstacle . . . to truth.” He assures the readership that “our battle . . . is not toward persons, but toward ideologies” and promises to be more positive in the future.29 Data in Figure 3, detailing the actual trajectory of topics over the course of ten years, allows us to verify whether Corrazza’s hope was realized.

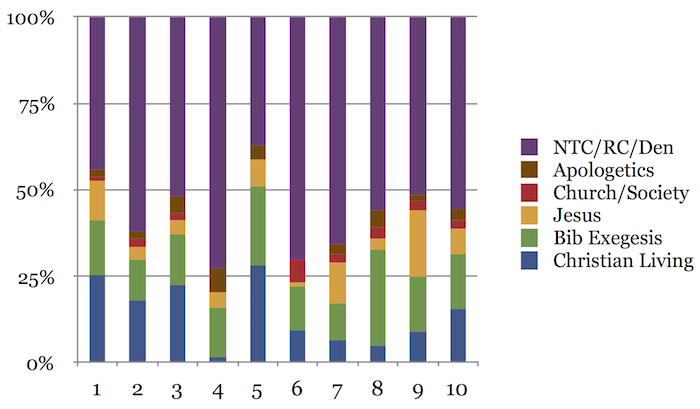

Figure 3: Relative Focus on Topics by Year (1954–1963)

Research Question #3: Do the articles change focus over a period of time?

While there are small variations from year to year and a change in editors in 1959 (year 6), the focus of the journal remains on biblical patternism regarding the New Testament church in contrast to primarily Roman Catholic doctrine and practice. In 1962–1963, numerous articles in the SdR reported on Pope John XXIII’s convocation of the Vatican II Council (1962–1965), the reform movement that updated Roman Catholicism. While more examination is required over the reception of Vatican II, overall there was great delight that it confirmed much of what the Church of Christ emphasized, a need to return to the origins of the gospel. Pope John XXIII recommended that a Bible be found in every home, la Bibbia in ogni casa, which the Churches of Christ subsequently used as its slogan for the Bible correspondence course and for distribution of the first modern-day translation of the New Testament in Italian, translated from the Greek by the former priests Fausto Salvoni and Italo Minestrone.

Research Question #4: What effect did New Testament patternism have on the identity of the Churches of Christ in subsequent years?

One of the great positive legacies of the American missionaries, in addition to the high view of the Bible, was the development of local leadership. In the 1960s, the Churches of Christ continued to grow with new missionaries and Italian workers. A second Bible school was established in Florence (Gianfranco Sciotti, a child from the Frascati Orphan Home, was a teacher/director from 1970 to 1982). Fifty years after its inception, church communities existed in sixty Italian cities with approximately 1,500 members, and there had been over forty Italian evangelists throughout its history.30 But it never fulfilled its early promise due to what I believe are three factors.

First, Vatican II’s call for ecumenicity effected a sea change in attitudes among Italians. In addition to other things, it called for respectful cooperation with Protestants as “separated brothers” who are saved and bring others to salvation.31 The “enemy” had shifted positions and therefore was never as easy to combat, yet evidence in Church of Christ literature points to a continued waging of battle. Second, neo-humanism was sweeping Europe, and religion was increasingly marginalized. According to Gerald Paden, yet a third Paden brother, “Italy was entering the age of materialism . . . manifested by increased indifference . . . and almost total apathy . . . toward biblical issues.”32 Third, by the 1970s, the Church of Christ mission fell victim to sectarian divisions within its own denomination. The emphasis on having the correct New Testament pattern for its ecclesial structure, together with the notion of silence in the Bible as being prohibitive rather than giving freedom for practice, had the unintended consequence of a legalistic approach to the Bible, a problem with which its American counterparts suffered as well. One church would “disfellowship” another church; issues became divisive.

If the focus of the initial beachhead and following years had been on the central themes of the gospel, rather than a continual responding to the perceived threat vis-à-vis Roman Catholicism, an alternative story might have been written. To be sure, such hindsight is much easier from a distance than in the midst of such complex times. Be that as it may, there is a very real possibility that inchoate contextualization of the gospel was happening by certain Italian churches in healthy ways, but unfortunately critique from the American missionaries and the loss of financial support from American churches made these moves untenable.33 Many left the Churches of Christ at this time. If only Corrazza’s words in that first editorial had remained the touchstone of the Restoration Movement’s work in Italy, “not to engage in polemics nor to combat any religious community . . . but simply spread the word of love preached by Christ.”34 Yet, the historic tensions with the Roman Catholicism of the time dictated a different path.

My research journey began in 2001, with a conversation I had with a matriarch of the Milano Church of Christ, Enrica Salvoni. She expressed her concern that the Churches of Christ had lost their distinctiveness. At its inception, the Churches of Christ in Italy were defined as the ones who studied the Bible, taught the love of God, had fellowship (agape) meals together, shared communion around the table. “But now,” she lamented, “even the Catholics do that! So, who are we now?”35 This question still echoes in my mind as I consider this formative period of the Italian Churches of Christ.

Janine Paden Morgan, PhD, is a missiologist and instructor at Abilene Christian University’s College of Biblical Studies. A third culture kid, she has a lifelong interest in how cultures and Christianity interact, and she teaches courses that reflect that interest. She has been active in cross-cultural ministry throughout her life (Italy, Scotland, and Brazil) and most recently for nine years in international study abroad education (England, Germany). Her academic research focuses on the role of ritual in spiritually forming communities, contemporary ecclesiology and mission, and the World Christian Movement. Janine and her historian husband Ron enjoy traveling the world with curious and like-minded students on mission with God.

†Adapted from a presentation at the Thomas H. Olbricht Christian Scholars’ Conference, Lipscomb University, Nashville, TN, June 7–9, 2017.

1 Roy Palmer Domenico, “ ‘For the Cause of Christ Here in Italy’: America’s Protestant Challenge in Italy and the Cultural Ambiguity of the Cold War.” Diplomatic History 29, no. 4 (2005): 632.

2 Ibid.

3 Joe Chisholm, “A General Report on the Italian Work,” in The Italian Lectures, ed. Jimmy Woods (Lubbock, TX: Dennis Brothers, 1950), 70.

4 Jack McPherson, “Workers Together with God,” in The Italian Lectures, ed. Jimmy Woods (Lubbock, TX: Dennis Brothers, 1950), 89.

5 Cline Paden, “313 Present for Second Service in Italy,” in The Italian Lectures, ed. Jimmy Woods (Lubbock, TX: Dennis Brothers, 1950), 96.

6 Harold Paden, “Eighteen Baptisms in July; 4000 Attend Classes,” in Frascati Orphan Home Paper 1, no. 8 (1949): 1.

7 Cline R. Paden, “Work Grows in Italy Despite Catholic Opposition,” in Frascati Orphan Home Paper 1, no. 12 (1949): 1.

8 Ibid.

9 Domenico, 637.

10 Rodolfo Berdini, “From Persecutor to Persecuted,” in Frascati Orphan Home Paper 2, no. 8 (1950): 2.

11 Cline Paden, “An Arch Priest Is Baptized in Italy,” in Frascati Orphan Home Paper 2, no. 1 (1950): 7.

12 Carl Mitchell, “Italy: Fifty Years of Progress (1949–1999)” (unpublished paper, copy in private Bobbie Paden collection 1999).

13 “Beachhead,” Time, January 23, 1950, 55.

14 “Italians Harass U.S. Evangelists,” Life Magazine, February 20, 1950, 95–99.

15 Domenico, 635.

16 Ibid., 642.

17 Jimmy Wood, “Italian Government Orders Orphanage Closed,” Frascati Orphan Home Paper 1, special issue (1949): 2.

18 Jimmy Wood, “Our Trip to Washington,” Frascati Orphan Home Paper 2, no. 2 (1950): 5.

19 Domenico, 651.

20 Ibid., 651.

21 Jimmy Wood, “Closure of Frascati Orphan Home” in Frascati Orphan Home Paper 9, no. 11 (1956): 1.

22 Carlos Mondragón, Like Leaven in the Dough: Protestant Social Thought in Latin America, 1920–1950, trans. Daniel Miller and Ben Post (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2011), 19–22.

23 My colleague Cindy Roper and I went to the Scuola Biblica di Firenze archives in Florence, Italy. Employing qualitative content analysis, we examined and coded the rhetoric used in journal articles in Il Seme del Regno (SdR, the seed of the kingdom), a monthly journal for Italian Churches of Christ, from its inception in 1954 through a ten-year period.

24 Marisa Sala, interview by Janine P. Morgan, May 9, 2016.

25 Nathan Hatch, “The Christian Movement,” in American Origins of Churches of Christ: Three Essays on Restoration History, by Richard Hughes, Nathan Hatch, and David Edwin Harrell Jr. (Abilene: ACU Press, 2000): 32.

26 Sandro Corrazza, “Editorial,” in Il Seme del Regno 1, no. 1 (1954): 1; translation mine.

27 Sandro Corrazza, “Editorial,” in Il Seme del Regno 1, no. 4 (1954): 2; translation mine.

28 “Letter to the Editor,” in Il Seme del Regno 2, no. 12 (1955): 2; translation mine.

29 Sandro Corrazza, “Editorial,” in Il Seme del Regno 2, no. 12 (1955): 2; translation mine.

30 Mitchell.

31 “Catholic Principles on Ecumenism,” in The Documents of Vatican II: All Sixteen Official Texts Promulgated by the Ecumenical Council, 1963–1965, ed. Walter M. Abbott (New York: The America Press, 1966), section 3.

32 Domenico, 653.

33 I would like to continue further research on this question in the future.

34 Corrazza, “Editorial,” Il Seme del Regno 2, no. 12 (1955): 2; translation mine.

35 Enrica Salvoni, interview by Janine P. Morgan, July 8, 2001.